“We have been wanting to talk with you for a very long time,” historian Bruce Pascoe says in his introductory essay to Void, now on show at the Canberra Museum and Gallery.

“We wanted to tell you the story of the land, the land where you now eat and sleep. We wanted you to know her lore and learn how to respect her, to look after her welfare, [to] ensure that there is a beach and grass and clean water for your grandchildren …”

They’re powerful words after this summer of destruction, a challenge thrown down by an exhibition that asks us to look into what is often construed as emptiness but is, in fact, anything but.

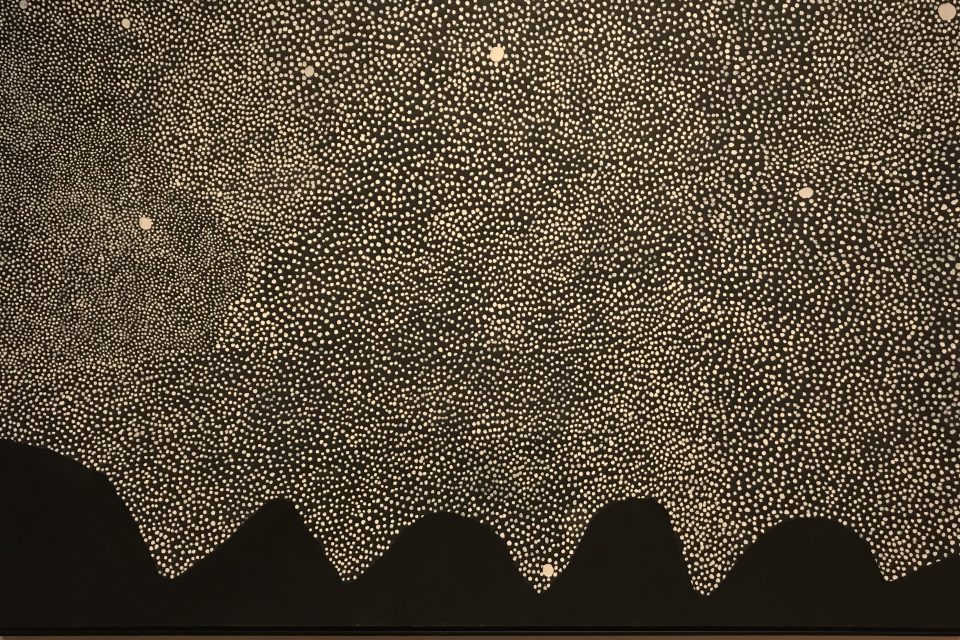

The Void is a travelling exhibition of contemporary Aboriginal artwork, referencing apparently empty spaces that are actually filled with story and meaning for those who know how to read them. And it also makes the point that this continent was never terra nullius, either unoccupied or uninhabited.

Void shows us that what was presumed to be empty space is filled with stories and meaning.

Dr Daniele Hromek, a Budawang woman from the Yuin nation, whose country was originally Currowan, told the story of her own family’s relocation and sense of absence at the Void exhibition launch.

“Around 150 years ago our ancestors made an impossible decision to leave those lands,” she said. Their journey was made for multiple reasons from the toll of introduced diseases, stricter regulations of reserves, the assimilation of lighter-skinned Aboriginal children and massacres in Yuin country. It took them north to country near Nambucca Heads.

“I’m pretty sure they followed familiar walking routes, from the Queensland to the Victorian border. There’s one route that runs down the coast and one down the mountains. Coastal people stayed with coastal people, mountain people with the mountains,” she said.

“It would have been heartbreaking not to be able to care for that Currowan country. But if you scratch a bit further you find sisters Elizabeth and Catherine Marshall. These two women did whatever it took to keep their family together.

“They made this impossible decision to leave their traditional lands, but in the end, they did it for love to keep their families together and as women and mothers, they did it to keep their children with them. To keep them safe so there was continuity.”

As a consequence, Hromek said, her family had grown up without traditional country, a decision that indelibly marked the lives of everyone who came after.

“Those of us dispossessed of our country do have a void. But for our family, these voids were filled for love for each other, despite being dispossessed, despite having the forces of colonisation and invasion continuing.”

Hromek said the Currowan fire’s destruction had made that dispossession very hard to bear as so many places and living things were made void by the power of the blaze.

“I tell you this story of my family whose origins are of this country. I tell you these stories to keep them alive and keep the memories there,” she said.

At the centre of the exhibition, Jonathan Jones’ installation, dhawin-dyuray, or axe-having, seems to represent the outline of an undulating landscape but is, in fact, the surface of a traditional axe-head in close detail. The soundscape weaves together wind, rain, birdlife and the axe’s sound, using a stone from Wiradjuri country.

James Tylor, (Erased Scenes) From an Untouched Landscape #7, 2013, inkjet print on Hahnemühle paper with hole removed to a black velvet void. Image courtesy of the artist and Vivien Anderson Gallery.

Ceramic vessels made by Dr Thancoupie Gloria literally wrap a void with stories, while James Tylor takes classic pastoral landscapes and carves out geometrical shapes. From a distance, these look like elements placed over the images; in fact, at close range, they are holes, voids or absence cut from the landscape onto black velvet backing.

There are also works by major Aboriginal painters including Mick Namarri Tjapaltjarri, bark painter John Mawurndjul, Freddie Timms and Doreen Reid Nakamarra.

Opening the exhibition, arts minister Gordon Ramsay said: “This is a very powerful time when the lands of the Ngunnawal and the Ngarigo, the Dharug people and the Gadigal people and Dharawal and so many other peoples and nations across the place we now call Australia have been impacted so devastatingly.

“This is an important time to acknowledge people who have been caring for country and community for lifetimes … We share this country now, all of us.

“The void is anything other than empty.”

Void is curated by Emily McDaniel, in conjunction with UTS Gallery and Bathurst Regional Gallery, and presented nationally by Museums and Galleries of NSW. It’s at the Canberra Museum and Gallery until 3 May.