Mountain Grevillea, here on Black Mountain, grows commonly in Canberra Nature Park. The characteristic protruding style, which produces pollen, is obvious here. Photo: Ian Fraser

In the springtime month of May in far-off and long-ago England, a man was born and died – in 1749 and 1809, respectively. He never came to Australia, so how could he possibly be of interest to a Canberra Riotact column on natural history?

Well, for admittedly somewhat tenuous reasons, his name lives on in one of the most familiar Australian plant groups, found widely in Canberra bushland and gardens.

Charles Francis Greville was born into the aristocracy and was always comfortably off and thus able to indulge his interests in both art and the sciences.

He collected art and antiquities and was a member of the quaintly named Society of Dilettanti that promoted the study and recreation of ancient Greek and Roman art.

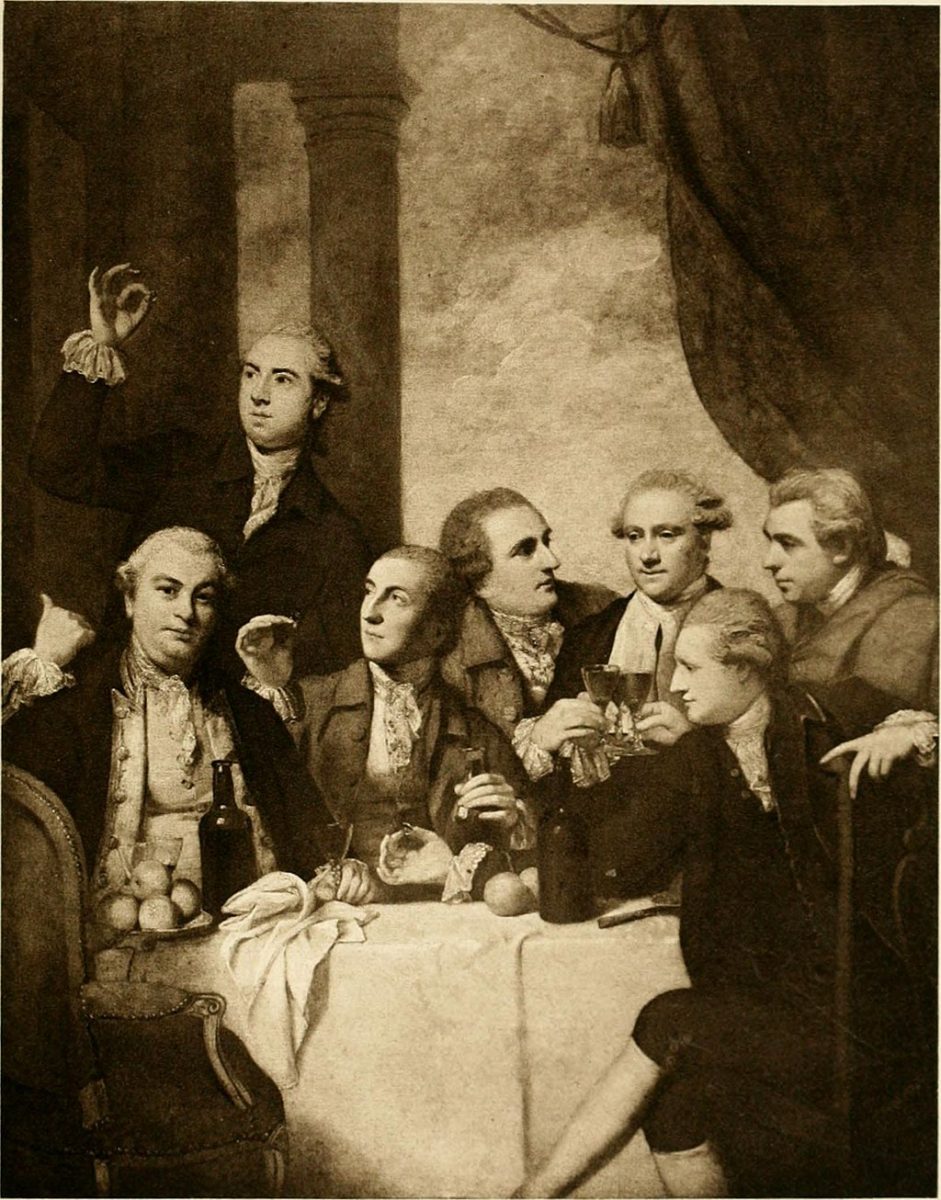

The Dilettanti Society, after Joshua Reynolds. Constantine, second Lord Mulgrave; Henry Dundas, afterwards Lord Dundas; the Earl of Seaforth; Charles Greville; John Charles Crowe; (6) Sir Joseph Banks; and (7) Lord Carmarthen, afterwards fifth Duke of Leeds (with stick). Image: Wikicommons.

With an interest in precious stones and minerals, he joined the Royal Society and became a good friend of Sir Joseph Banks (we’re now getting closer to Australia!) You’ve probably read his deathless An Account of Some Stones said to have fallen on the Earth in France, and a Lump of Native Iron said to have fallen in India …

He was a passionate gardener and his custom-built house in Paddington Green had a sprawling garden and glasshouses to grow tropical plants which Banks helped to obtain.

The spectacular Fernleaf Grevillea in Queensland is the basis of many garden hybrids. However, their big flowers attract big aggressive birds like wattlebirds, so they aren’t suitable for smaller birds. Photo: Ian Fraser

With Banks, he helped found the Society for the Improvement of Horticulture, which evolved into the prestigious Royal Horticultural Society. He also inherited a seat in parliament and was quite active there, especially in Treasury.

(Actually, Greville is not nearly as well-known as his young mistress, Amy Lyon, later Emma Hart, whom he supported, along with her mother, for some time. She was famous as the muse and model of painter George Romney. Greville wasn’t married so there was no impediment to the relationship, but it later became expedient for him to marry Emma off to his uncle in Naples, Lord Hamilton. She thus became Lady Hamilton and later gained fame – or infamy, if you prefer – as the not-at-all-secret mistress of Lord Nelson. She was a very interesting woman, and it’s worth finding out more)

It certainly wasn’t for this aspect of Greville’s life that in 1809 the great Scottish botanist Robert Brown, who had sailed and collected with Matthew Flinders, named a very important genus of plants from Australia – Grevillea – in his honour.

Greville certainly hit the jackpot, as it were, because there are some 350 Australian species now known as Grevillea, including some of the best-known Australian plants, and another five in Indonesia, New Guinea and New Caledonia.

They include shrubs, trees and ground covers, from the snowy alps to the central deserts and from heathlands to rainforests. The flowers are distinctive, with a long protruding style; often, the flowers grow in glowing red, orange or yellow clusters at the end of branches. This has led to the name spider flower often being used, though usually they’re just referred to as grevilleas.

New Holland Honeyeater in the National Botanic Gardens with grevillea pollen on its forehead. Photo: Ian Fraser.

These colours are widely flaunted by bird-pollinated flowers, and grevilleas certainly are. They produce a strong nectar flow and honeyeaters use long curved bills to probe the flower for the rich energy reward at the base. In the process, their forehead collects pollen from the tip of the style and takes it to the next flower they visit.

Silky Oak, named for the timber, is a grevillea growing to 40 metres tall with glowing golden flowers from the wet forests, including rainforests, of southern Queensland and northern New South Wales. Given this, how well it does as a street tree in dry cold Canberra is surprising.

Many hybrid cultivars are sold in nurseries for garden use, though there are a couple of things to be aware of. Make sure they are frost-hardy and don’t mind our heavy clay soils as sometimes species suitable only to coastal conditions appear on the shelves.

And if you want to attract birds, it’s best not to plant ones with big showy flowers, attractive as they undoubtedly are. The problem is that these show-offs’ huge nectar production attracts the bird garden bullies, such as Red Wattlebirds and Noisy Miners.

Once these find the flowering bush, smaller birds such as Eastern Spinebills and pardalotes will be chased mercilessly from your yard and you’ll have very few species to enjoy for as long as the Grevillea is flowering. Smaller-flowered local species are a much better idea as bird attractors.

Charles Greville wasn’t particularly admirable, at least with regard to his treatment of Emma Hart, but a story’s a story and while we’re enjoying the wonderful grevilleas, we might as well know why they’re called that!

Ian Fraser is a Canberra naturalist, conservationist and author. He has written on all aspects of natural history, advised the ACT Government on biodiversity and published multiple guides to the region’s flora and fauna.