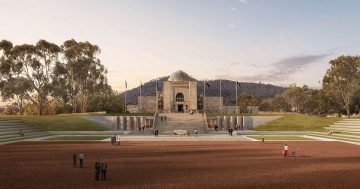

An artist’s impression of how the redeveloped War Memorial will look. Image: AWM

When did the word ‘consultation’ become the beginning and end of a genuine voice from the community on major policy and infrastructure decisions?

It seems like there’s no end to websites with ‘your say’ in their title, administered by governments to provide a platform for feedback from their constituents on everything from planning strategies, major works, or even policy proposals in contentious areas.

Yet, when the period for consultation passes, it seems like no real weight is given to the feedback received unless it aligns with the proposed approach that was offered in the first place.

Take the Australian War Memorial expansion, for example.

Over 600 submissions were received (the most ever received in the Memorial’s history), and it has been reported that less than 10 of these were in favour of the proposed expansion,* which includes demolishing Anzac Hall and cutting down over 100 trees.

And yet, the National Capital Authority has given the green light for early works to commence.

Over 600 people felt moved enough by the proposal to make a submission. That’s no insignificant number.

While some would argue that people only bother responding to these types of processes if they’re anti the proposal and that the silent majority are likely to be in favour, I would argue that if a consultation process is being offered as part of our democratic system, those in charge are obliged to take every single submission seriously.

And yet it feels like, despite there being more and more opportunities to ‘have our say’, what we actually say is rarely seen as important enough to impact the outcomes. The public impression of having consulted is more important than meaningfully responding to the feedback received.

I’ve worked at a number of places that deliver advice to government on contentious issues based on community views and actions. For example, I worked for one place where we would get thousands of people speaking out against certain government policies, contributing their views via official submission processes, and yet there was never a corresponding reaction to this wave of community action.

Instead, we would watch as much smaller groups of powerful industry stakeholders would consistently have more influence and sway than the thousands of individual Australians who came together as a community to register their opposition.

This pattern is seen across consultative processes. In planning and development, for example, people speak out against major new works or developments, but the project proceeds anyway. People rail against government policy that is open for public and expert comment, but nothing changes.

The argument is that we exercise our democratic voice in voting our leaders into government – but what kind of true democracy limits the voice of citizens to one decision every three-to-four years, especially when the choice we’re presented with is already narrowed to those who have access to education, wealth and ability to stand in elections in the first place?

If consultation processes are going to be open for public comment, where is the accountability on government institutions and agencies to actually act and report on the feedback they received?

How are we ensuring that the process is driven by a genuine, transparent and accountable commitment to the best possible outcome based on community views and not just driven by budgets and timelines devised and implemented by those in power?

Is it naïve to expect the community to have a genuine influence when responding to consultative processes that affect our public institutions, land and policies? Or is it time we added some teeth to these processes to ensure that our democratic power is real?

CORRECTION: Region Media has been informed that over 600 submissions were received by the NCA (not the AWM) and this was the most in the NCA’s history. A total of three submissions were in favour of the proposed expansion.