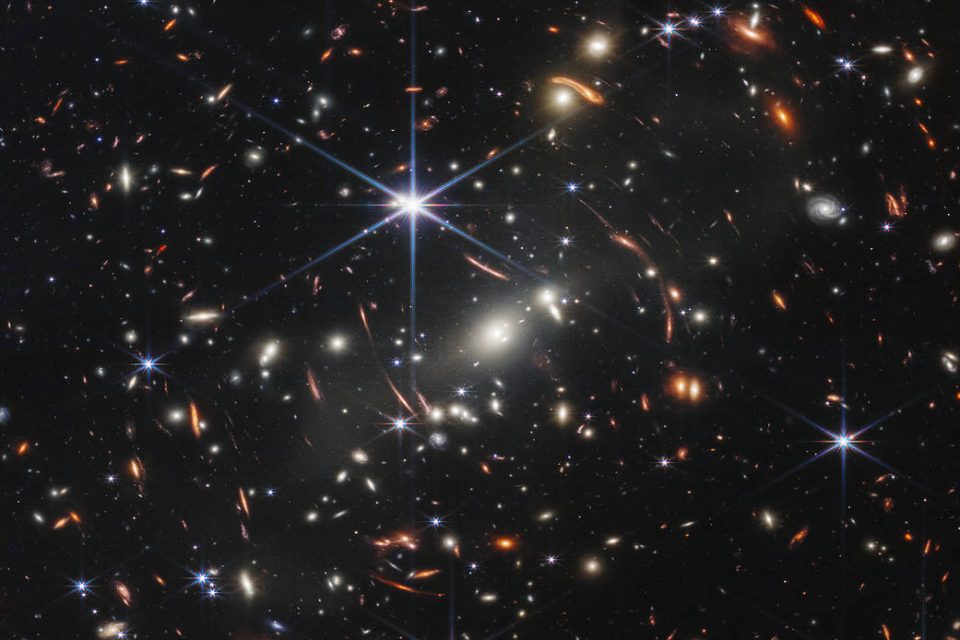

A photo captured by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope. Photo: NASA.

The first images from NASA’s new telescope are dropping much like our jaws. Although there are a mind-boggling 1.5 million kilometres between the James Webb Space Telescope and us, Canberra is helping to bring these snapshots of previously unseen reaches of the universe home.

On average, it takes about 10 seconds to communicate with Webb through NASA’s Deep Space Network, an international network of powerful antennas. Several of these lie near the Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve in the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex (CDSCC).

Richard Stephenson has worked at CDSCC for more than 30 years, talking to the spacecraft exploring the solar system and beyond.

“Canberra supports the DSN tracking schedule and when there are issues on Earth or in space my role is to restore the communication links as fast as possible,” he says.

Their current schedule contains more than 30 active missions, including tracking Webb.

“Our team started preparing for Webb months before its launch, testing on all DSN antenna to check compatibility and proficiency,” Richard says.

Richard Stephenson from the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex. Photo: CSIRO.

Webb launched on the European Space Agency’s Ariane 5 rocket from French Guiana on Christmas Day, 2021. While others were waiting for Santa’s sleigh to ride through the night sky, Richard and the rest of the Canberra team were tracking Webb as it headed for “Lagrange Point 2”, a spot in space where the gravitational forces of our planet and the sun are roughly equal, creating a stable orbital location.

“Under normal operations, tracking automation developed by CDSCC allows a controller to support up to three antennas at once,” Richard says.

As Earth rotates, each controller team will hand over to the next, providing 24/7 seamless communication with the spacecraft.

While the teams get to sleep through their nights, the antennas at each complex continue to work, controlled remotely by one of the teams from the other complexes.

“We call this ‘follow the Sun operations’,” Richard says.

“During daylight hours in Canberra, my team and I control the antennas at Madrid and Goldstone, as well as our own, to communicate with all the active spacecraft the network supports.”

But this wasn’t an option when deploying Webb.

Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex. Photo: CSIRO.

“Controllers had to maintain focus at all times ready to react to the spacecraft configuration changes the Webb team were making.”

Richard says the whole process for Webb has been flawless, from launch to arrival at Langrage point 2 to commissioning on Monday, 11 July, 2022.

“Webb is now a permanent fixture in our daily tracking schedule.”

US President Joe Biden revealed the telescope’s first full-colour image at a White House event later that day, of the galaxy cluster SMACS 0723. NASA describes it as the deepest and sharpest infrared image of the distant universe to date.

The slice of the vast universe covers a patch of sky about the size of a grain of sand held at arm’s length by someone on the ground.

In the subsequent images, thousands of galaxies – including the faintest objects ever observed in the infrared – have appeared in humankind’s view for the first time.

These images and the huge amount of data that comes with them are downloaded from Webb at the rate of 28 megabytes per second, which requires continuous contact with the spacecraft.

“Being 1.5 million kilometres from Earth does have its disadvantages when it comes to returning data, since covering this distance takes time.”

Webb might have provided “new challenges” but Richard says he wouldn’t give his job up for the world.

“The continuous evolution of the network and the amazing spacecraft it supports is the reason I’ve never considered doing anything else.”

Webb’s mission is designed to be at least five and a half years long, but it could be up as long as 10 years. The lifetime is limited by the amount of fuel used for maintaining the orbit, and by the possibility that components will degrade over time in the harsh environment of space.