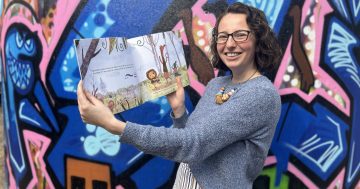

Max’s diagnosis turned life upside down for him and his family. Photo: Jemma Irving.

Bonython mum Jemma Irving was sitting with a friend at a play centre the first time she noticed something strange with her then three-year-old son, Max.

“He came running over to the table to get snacks,” she recalls. “One moment he was standing there talking and all of a sudden he stopped and just stood there motionless. His face sort of dropped a bit.

“It lasted about 10 seconds. I nudged his face a few times and he stayed completely zoned out and I thought ‘this isn’t daydreaming’.”

Ms Irving later discovered her son, now six years old, had joined the growing list of Australians diagnosed with epilepsy every 33 minutes.

She learned Max had experienced an absent seizure and had likely been through similar episodes that had gone unnoticed before.

Like most, her understanding of epileptic seizures was limited to the type called “tonic-clonic”, involving violent muscle contractions and loss of consciousness.

In fact, there are 40 documented types of seizures and a vast spectrum of how they present in each person.

Epilepsy ACT director Fiona Allardyce hopes to raise awareness of this little-known reality.

“Most people think there is one type of epileptic seizure – the one they see in the movies where they collapse, shake and froth at the mouth,” Ms Allardyce says.

“It can look like that. It can also look like they’re daydreaming or having unusual movements and there are many more variations that can be experienced.

“Most of the time they’re completely unaware it has happened. But epilepsy can be life-threatening, so it’s important to raise awareness of the different ways it can present.”

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder in which nerve cell activity in the brain is disrupted, causing seizures. One in 25 Australians is diagnosed with it in their lifetime.

Ms Allardyce says Max is one of more than 2344 people in the Australian Capital Territory currently living with a diagnosis of epilepsy. About 260 more will be diagnosed this year.

Throughout his ordeal, Max’s mum says her little boy has been ‘absolutely incredible and courageous’. Photo: Jemma Irving.

Despite the jarring statistics, she says the disorder remains widely misunderstood.

“It’s because there is a stigma behind it – people don’t want to talk about it, they don’t want to let their employers know because people instantly think of what they can’t do,” Ms Allardyce says.

“Often people don’t see the person; they just see the condition.”

For Max, the diagnosis was just the beginning of a gruelling journey.

The little fighter went through a trial-and-error process of nine anti-seizure medications to find one that worked for him. He endured a number of different types of seizures of up to 55 minutes, including full-blown tonic-clonic.

The damaging effect on his gross and fine motor skills meant he had to re-learn many skills through intensive physiotherapy, speech and occupational therapy, and hydrotherapy. His treatment continues today.

For Max and his family, life is now a waiting game to see how his epilepsy changes as he grows. There are multiple pathways it can take.

As for the journey ahead and what the broader community can do to help?

“We don’t need pity,” Ms Irving says. “Though suggestions are always made with the best of intentions, we can guarantee there is nothing you can Google we haven’t already.

“What we need is your support.

“The first year or two after diagnosis is full-on, our whole world can be turned upside down and we can spend months in hospital. If we do – please reach out. Sitting in the hospital is a terribly isolating experience, it can really break you down.”

Max spent four of 18 months at Sydney Children’s Hospital and The Children’s Hospital at Westmead following his epilepsy diagnosis. Photo: Jemma Irving.

Ms Allardyce says it can take six months to see a neurologist in the ACT once an adult has been diagnosed. There are no paediatric neurologists in the Territory at all.

To fill the void between diagnosis and meeting a specialist, Epilepsy ACT offers support.

“We develop management plans and determine what care and equipment families might require,” she says.

“We also do a lot of training and education at schools on how to recognise seizures, how to administer life-saving medications and so on. We also have support groups for families dealing with epilepsy, so they know they’re not alone.”

Families dealing with epilepsy can reach out to Epilepsy ACT for support.