Joe Slosu operated one of the Snowy Hydro Scheme’s most formidable pieces of equipment – the Tournapull. Photo: Joe Slosu.

Joe Slosu’s heart leapt into his mouth.

The Tournapull, a revolutionary type of earthmoving equipment, had earned a reputation as a ‘widow-maker’ among the workers on account of its terrible steering.

“We drove on unsealed surfaces which were steep, winding, wet, icy and narrow, and it wasn’t uncommon that roll-overs happened because drivers had no way of controlling the steering,” Joe says.

“Workers lost their lives to this bad design.”

Joe and his brother had survived four years as Tournapull operators when, on their last shift, the nightmare came true. His brother was at the helm when one of the machines jack-knifed, toppled and rolled down an embankment, only coming to a stop upside down in a river.

Joe, further back, watched in slow-motion horror.

“I thought he had been killed,” he recalls.

“People were rushing down the embankment to his aid, and it was a miracle he survived unscathed.”

Joe and his brother were among 100,000 people from more than 30 countries who worked on the Snowy Hydro Scheme.

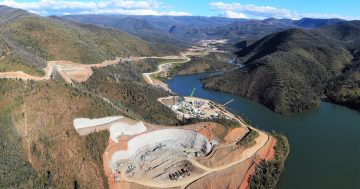

Work is now underway on Snowy Hydro 2.0. Photo: Snowy Hydro Facebook.

This October marks 75 years since then Governor-General Sir William McKell and Prime Minister Ben Chifley fired the first blast at Adaminaby, NSW, on 17 October 1949.

The scheme, spanning Tumut to Jindabyne, is still considered one of the civil engineering wonders of the modern world. It consists of eight power stations, 16 major dams, 80 kilometres of aqueducts and 145 kilometres of interconnected tunnels.

To honour its builders, the former workforce and their families will be invited to a reunion event in Cooma on Saturday, 19 October. Joe, who now lives in Sydney, will attend along with his wife of 66 years, Antonietta, and their daughter, Canberran Linda Slosu.

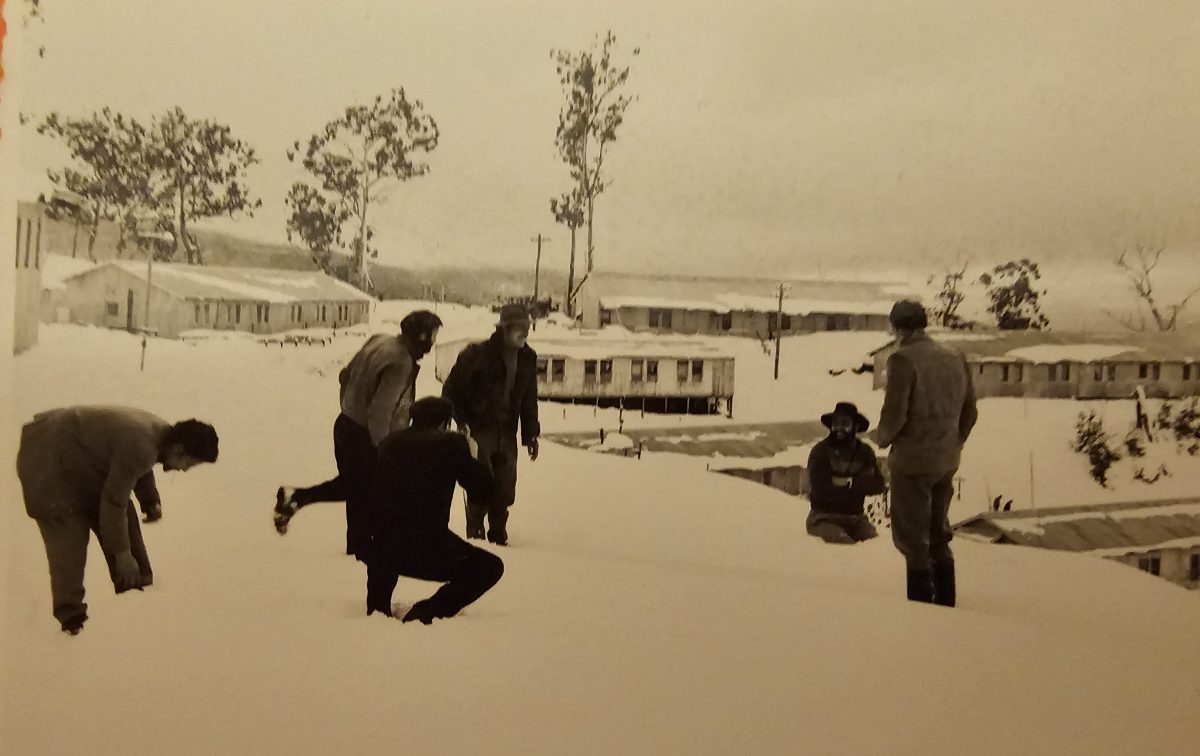

Workers at the Kenny Knob Camp. Photo: Joe Slosu.

“Every day, we faced the risk of rock falls, landslides, hazardous narrow tracks, injuries from large-scale heavy equipment and the effects of sub-zero temperatures, dust and noise,” Joe, now aged 90, recalls.

“Looking back, we took risks nobody would today. We were given helmets, boots and raincoats but not workwear for the job or climate – we wore our own ordinary clothes.”

But the outlook was still better than in Joe’s home city of Trieste in post-war Italy, where jobs were “short lived, underpaid and out of sight of the authorities”.

In March 1954, he and his brother left on board a ship “with the hope of secure work and a better life in Australia”. Joe was 20 at the time.

“After a short stay in a migrant camp, I was given a maintenance job on the then Sydney-Bourke railway line,” he says.

“We were based at Coolabah, our accommodation was very basic – we slept in tents near the railway line with a small kerosene camp stove.”

Shortly afterwards, they moved to the Snowy Hydro Scheme.

The shifts were hard – “eight hours, day or night, usually six days straight, irrespective of weather conditions or public holidays” – but the pay was good – “we were earning about four-fold the average weekly wage in Sydney – 35 to 40 pounds a week”.

“Despite being far away from our hometowns and missing our families., we were young men in our 20s and 30s, and we had fun times, too,” Joe says.

“I recall when excavating for the underground Tumut No 1 power station, there was a leaderboard at the rock face that showed how much the previous shift had tunnelled – there was always competition between the shifts.”

An overturned Tournapull machine on the Snowy Hydro Scheme. Photo: Joe Slosu.

After the initial two-year contract, he and his brother returned to Italy to visit their parents.

On the way back to Australia in 1957, it was love at first sight between Joe and a young woman who boarded the ship at Naples.

Looking out over the port from the ship’s deck, Antonietta and her friends were remarking to each other in Yugoslavian about how they wished they had a pair of binoculars just like the pair Joe was holding, not realising Joe’s father was Yugoslavian and he understood every word.

“My father handed over his binoculars to her and she was just stunned he understood what she was saying,” Joe’s daughter Linda says.

“It just blossomed from there, so by the time they reached Melbourne, they agreed to correspond via letter.”

Joe and Antonietta Slosu met on board a ship to Australia in 1957. Photo: Joe Slosu.

But that wasn’t enough. Whenever Joe finished work for the week, he’d be on the road in a Land Rover he’d picked up at an auction, and headed for Melbourne to visit her.

“I finished work at the scheme in 1958, and shortly after, Antonietta and I got married,” he says.

The couple celebrated their 66th wedding anniversary on 30 August with two children, four grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. All thanks to Snowy Hydro.

“It’s one of these migrant stories, where people came out for work, saying they’re only going to be here for a couple of years, but then they end up staying their whole life,” Linda says.

“My father now looks after his vegetable garden – he was in the backyard the other day digging potatoes – so apart from old age and slowing down a bit, they still do everything. He’s always been a hard worker.”

To find out more about the 75th anniversary reunion, visit Snowy Hydro.