John Napier worked on his parents’ sheep and wheat property, ploughing paddocks and helping with shearing until he was called up for service in 1942 and sent to New Guinea to help repel the advancing Japanese army. Photo: Napier family.

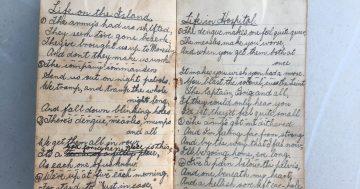

Paper was in short supply during World War II when Australia faced an aggressive Japanese enemy in Papua New Guinea.

A handwritten letter from home was worth more than gold.

“I don’t think anyone, only a soldier, knows how good it is to receive it,” John Napier, a 21-year-old soldier, wrote home to his family in the spring of 1943.

The eldest of nine children, John made every word count in his letters, as did his family. They would write in the margins of a completed letter to squeeze in a late snippet of news to him from their 1060-acre (429-hectare) sheep and wheat farm at Quandialla, near Grenfell, in NSW’s Central West.

His mother Maggie was perhaps the busiest, writing to “My dearest John”.

“Since last Tuesday Phyllis has a nice roan heifer and calf and this morning your red cow has a nice little red calf,” she wrote. “He hasn’t come close to the house yet but they say he’s a real beaut.”

Eighty years later, on the anniversary of John’s death, the letters were read by his niece Tori Davidson when about 50 descendants gathered at Quandialla Cenotaph for a wreath-laying service on Saturday, 14 October.

In his letters, John tells his father Sydney and Maggie not to worry about him because he is fairly safe.

“Don’t think I am frightened and worry about me because I’m in the pink. It won’t be long before we put these yellow chaps back from where they belong and then home for good, won’t it be great. I intend to be a free man from then on, I would have done my share and been away from home long enough. They will never catch this chap again.”

John described his best mate Harry Fanning as “a great soldier and gaffer and a better mate I never had”. This pleases Maggie. “… see that you are as loyal to him in return,” she writes back.

“About the Good Soldier. Don’t run too many risks John,” his mother wrote. ”We don’t want medals etc., if you return fit and well and soon.”

At the time, Maggie did not know her oldest boy was approaching the Battle of John’s Knoll-Trevor’s Ridge, which was fought from 12-13 October, 1943. Her letter was written on 10 October and would never have reached him.

The fighting took place as the Australians advanced towards the main Japanese defensive positions around Shaggy Ridge and Kankiryo.

Three companies of Japanese troops launched a counter-attack, supported by heavy machine-guns, mortars and artillery, early on 12 October, focused mainly on the single Australian platoon holding John’s Knoll.

As days turned into weeks afterwards, the Napiers’ letters started coming back to their farm from the dead-letter office. They knew something must have been wrong but were not told anything. They thought he had either been killed or taken as a prisoner, says John’s younger brother Charles, the only surviving member of the family, who remembers those terrible weeks. He was 14 at the time.

“My uncle and his wife, who were our neighbours, brought the news over one Sunday morning,” Charles said. “A telegram had arrived at the Quandialla Post Office. The worst thing was, he had been killed two or three weeks before they even knew.”

Australians fought the Japanese in New Guinea’s jungles and rugged mountains in 1943. Photo: Australian War Memorial.

Writing to the Napiers on 11 November, 1943, Lieutenant David McCrea said: “John to us was a very real mate, his cheerful personality, his capacity to joke, when the going was hard and his friendly manner to all, brought him many friends in the Army.”

Two days before he died, John was sent out with the remainder of his platoon into a steep jungle away from the rest of the battalion. While the platoon was there, Japanese soldiers attacked the battalion.

“My platoon which John was in was ordered to go down the track and try and make contact with the battalion,” Lieutenant McCrea wrote.

Towards evening, they came into contact with Japanese soldiers, and John’s friend Ron Dean of Wirrinya was killed. They remained in their position with wounded soldiers. Then John and Sgt Des O’Connor were sent off to make contact with the battalion and although the going was hard, made it through and returned with further orders.

Charles Napier, 94, the last surviving member of John Napier’s family, at the Quandialla Cenotaph on Saturday, 14 October, 2023. Photo: Michelle Thistleton.

The next morning, his platoon moved into the battalion area and was placed in a reserve area, where the men dug into foxholes. It was then the Japanese opened fire on them. One of the bomb bursts from the Japanese killed John instantly.

His descendants later learned John’s mate Harry Fanning carried his body from the battlefield, two years after he had enlisted and just three months after he arrived in Papua New Guinea, where he is buried.

Original Article published by John Thistleton on About Regional.