Hands holding multi generation family paper, family wellness, health insurance concept Photo: Sewcream Studio.

In Australia, we have an Intergenerational Report completed by the federal government every few years.

To quote the Treasury website: “These reports project outlooks for the economy and the Australian Government’s budget over the next 40 years. They examine the long-term sustainability of current policies and how demographic, technological and other structural trends may affect the economy and the budget.”

These reports are normally very good, totally necessary and worthy documents. When released, they are heavily discussed and can achieve headlines as they can be alarming.

The first intergenerational report was in 2002. Which makes me wonder – were there important intergenerational issues before 2002? More on that later.

What are the current intergenerational issues that need to be covered and reported on? They would include population policy and dealing with changes in demographics; budgets, deficits and future debts; infrastructure and planning; the environment; changes in technology and skill requirements; housing affordability, globalisation; regional conflict; and much, much more.

At the very recent ACT Assembly election, the party of independents came out with an announcement that the ACT would lead the way and be the first jurisdiction in Australia with a Future Generations Act.

It sounded good and received fanfare as party policies often do during an election. I wasn’t sure it was something worthwhile, but I didn’t want to appear critical of independents during the election as I, too, was running as an independent.

The announcement used as its model the very first and only Intergenerational Act and Commissioner based in Wales.

It is certainly true that intergenerational issues are very much alive – particularly climate change, the cost of housing, the growing government debt, changing technology, gender roles and issues and global conflict, among others.

But how does a Future Generations Act fix that? Do we need another micro bureaucracy to do this? Shouldn’t it be the role of existing parts of government?

A recent report from the very first Welsh Intergenerational Commissioner, who headed up the intergenerational commission for seven years, was glowing when assessing their own work. The commissioner was interviewed at the end of their seven years. Here are two salient quotes: “One of the big changes brought about as a result of the Act is that we’ve pretty much stopped building roads in Wales.”

And: “My recommendation was not just a minister for prevention, but a minister for prevention with a 10 per cent top slice of every budget across government at their disposal to coordinate action across government and invest in preventive interventions.”

Those seven years costs the Welsh the equivalent of around $25 million. That’s a lot of money for navel-gazing and blocking roads.

It can be done without extra bureaucracy: fix the budget so future generations won’t have a massive debt hanging over their heads; ensure children leaving year 12 have the best literacy and numeracy skills they can have, otherwise their lives will be more difficult than they should be; guarantee that apartments and units are properly built so the next generation can buy something that won’t fall apart; increase public housing so there is less homelessness; better resource and fund the Integrity Commission so that we can have increased trust in governments of any party; continue the confrontation with climate issues where the ACT leads the way … that ought to keep departments busy for a while.

When I was growing up, my parents and the governments of the day saw the biggest issues for the next generation, us baby boomers, were jobs and education. These were the priorities of our parents, who grew up living through a global economic depression and then a global war.

Back then, we also had an emerging middle class. The purchase of a house, while always difficult, was eventually more achievable, and most of us achieved that. Manufacturing was a very large part of our economy, apprenticeships were readily available, the global economy didn’t really exist, technology was slow to develop and easily managed. A worker had a job for life, unemployment was low and the future was only blighted by the fear created by the Cold War.

Perhaps there is some hyperbole or some understatement in my views, but hopefully, you get the gist.

So, the intergenerational issues were not so important, indeed the word intergenerational didn’t really exist.

Intergenerational issues are now ongoing and vitally important. The creation of a local special commissioner or legislation would add to the complexity and make processes for planners, policymakers and others much more difficult. We must focus on the excellent intergenerational reports produced by the federal government and then let governments, the ACT Government, in particular, do what they should be doing – dealing with it. There is no time to develop a new commission just because it sounds good. We have enough public servants, clever ones, already.

(Note: the word ‘intergenerational’ is a great buzzword to use in job interviews.)

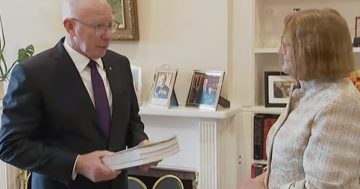

Peter Strong was a Canberra business owner and CEO of the Council of Small Business Australia (COSBOA) for 11 years. He now consults on community economics.