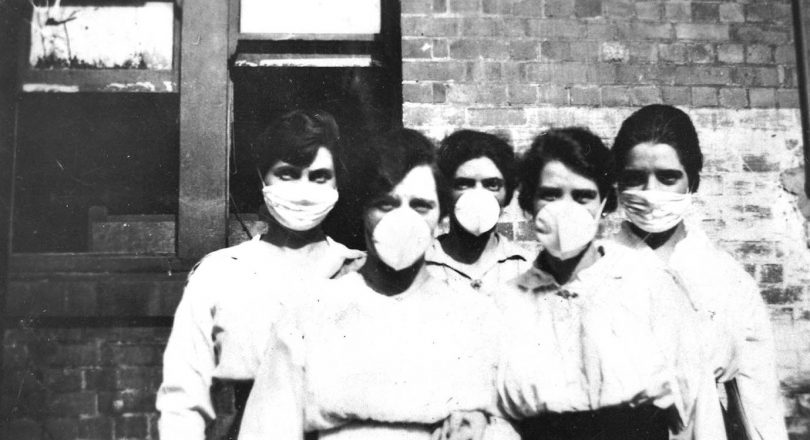

Women wearing surgical masks in 1919 during the Spanish flu pandemic. Photo: National Museum of Australia.

Australia has flattened the COVID-19 curve and managed to get transmission of the virus under control, but as winter approaches, Australians are being warned about a second outbreak that could be more deadly and spread more rapidly than the first.

Although the second wave of the Spanish flu – a common comparison point for COVID-19 – was much deadlier than the first, the circumstances around its spread might not be as relevant a century later, said ANU historian Professor emeritus Joan Beaumont, who has studied the post-war outbreak.

“In the case of the Spanish flu, what kept it going was the movement of people,” she said, referring to the large scale transits at the end of WWI that exposed hundreds of millions of people to the virus.

“So far we have had the advantage of being able to close our borders and that is going to be the real challenge, of how you are going to open your borders and expose yourself to the possibility of reinfection.

“Many experts say that every pandemic is unique and that comparisons you can make are limited. There has certainly been a lot of similarity in terms of … the social responses.”

It’s often believed that the second wave of the Spanish flu pandemic was more deadly because the virus had mutated. But ANU infectious diseases expert Professor Peter Collignon says that’s not the case.

“The reason the Spanish flu was more deadly is because 80 per cent of people who died had bacterial infections, not the virus. In army studies, about 80 per cent of people who died had either pneumonia germs or staph or something called ‘group A strep’ in their blood,” he said.

“The reason people died in the Spanish flu was because of secondary infections and no antibiotics. Most people died on day 10; it was not sudden. They had an illness, got better and then got sick again.”

The risk of secondary infections is presenting itself as a problem in Australia right now, he said.

“COVID-19 may be different, but in ICUs at least, a large proportion – maybe 50 per cent of people – are getting secondary bacterial infections and they are the ones who are dying more often,” said Professor Collignon.

The virus – which would not in itself be deadlier during a second wave – could nevertheless cause more deaths in winter because of its ability to spread more quickly, similar to influenza and other respiratory diseases.

“That may be why it is so bad in Europe and the United States, because it’s spreading in winter and not being identified because such a large proportion of cases are mild or even asymptomatic,” said Professor Collignon.

ANU infectious diseases expert Professor Peter Collignon says secondary bacterial infections were responsible for the majority of deaths attributed to Spanish flu, and to a certain extent, COVID-19. Photo: ANU.

However, the outlook here is more optimistic with measures that can readily respond to, and minimise, threats from major viral stimuli.

“So far most of the cases we have had in Australia are related to risk factors you can easily identify, and those risk factors, in general, have either been really well managed or removed,” said Professor Collignon.

Such risk factors include international travel and clusters of infections on cruise ships.

“A second wave is a question, but having said that, we have lots of testing, lots of follow up and lots of quarantining.

“I think we will see more cases in winter, but I think we will be quickly on top of them and will make the clusters small rather than large and that will stop the spread.”