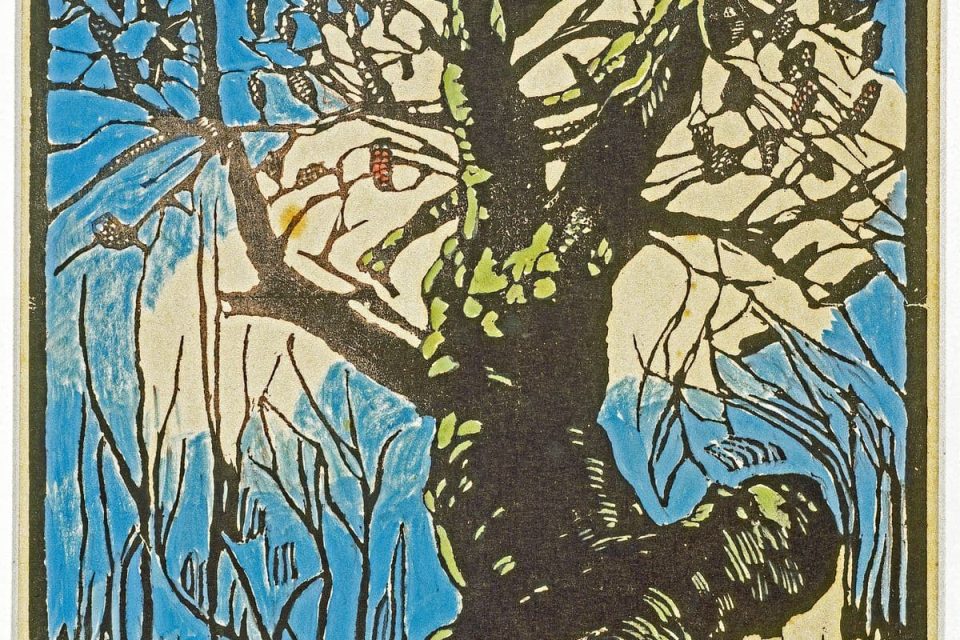

Margaret Preston’s Bird of Paradise brings a strong modernist influence to printing techniques. Image: NGA

Australian art, in the period between the wars, was dominated by a generation of brilliant women artists.

They included Ethel Spowers, Eveline Syme, Margaret Preston, Dorrit Black, Grace Cossington Smith, Clarice Beckett and Olive Cotton, and it is their work that features in a major exhibition at the NGA, Know My Name: Making it Modern.

Reasons why most of the best artists in Australia in the 1920s and 1930s were women and why so many of them embraced different facets of modernism in their practice aren’t immediately clear.

Some art historians adopt a demographic argument – they argue that many of the men who could have emerged as artists died on the battlefields of the First World War, and those who were left were absorbed into critical production or went abroad and made their careers away from Australia.

Another, and to me a more plausible argument, is an economic one. The fine arts, during the Great Depression, were not particularly financially viable and most of the women who could indulge in the arts had private means and did not particularly bother about earning an income.

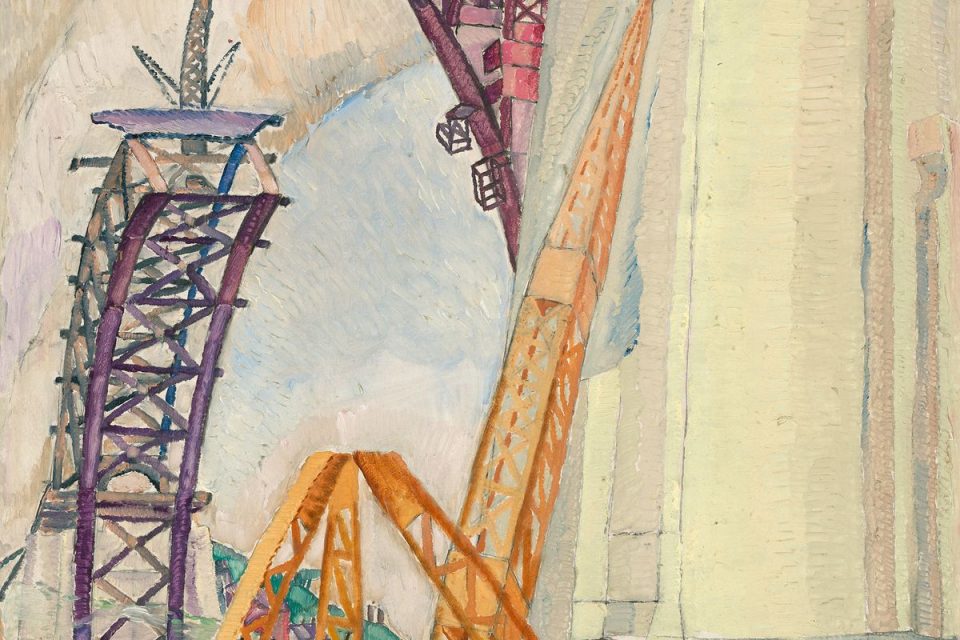

Ethel Spowers’ The Gust of Wind exudes energy and dynamism. Image: NGA.

Spowers and Syme were heiresses to newspaper empires, Preston married into money and others had inherited financial security that they could supplement with a bit of teaching.

Most of these artists could travel freely and frequently abroad and were attracted by some recent developments in art. They felt no need to compromise their artistic endeavours as making a living from their art was not a primary consideration.

Many of these women artists, when viewed in retrospect, embraced a ‘modernist perspective’ in as far as they broke with the conventions of academic naturalism.

Colour and form were employed for artistic, formal and compositional purposes rather than purely as strategies to mimic observable nature. Looking through the exhibition, it is clear that no singular concept of modernism prevailed. It was more of a question of breaking with the conventions of the past rather than, in any united way, embracing a path into the future.

These artists were also not constrained by traditional art forms, the big slabs of oil paint to describe the Australian landscape as glorified by the Heidelberg boys (who were primarily male artists) or flattering portraits – all ultimately looking back to Europe.

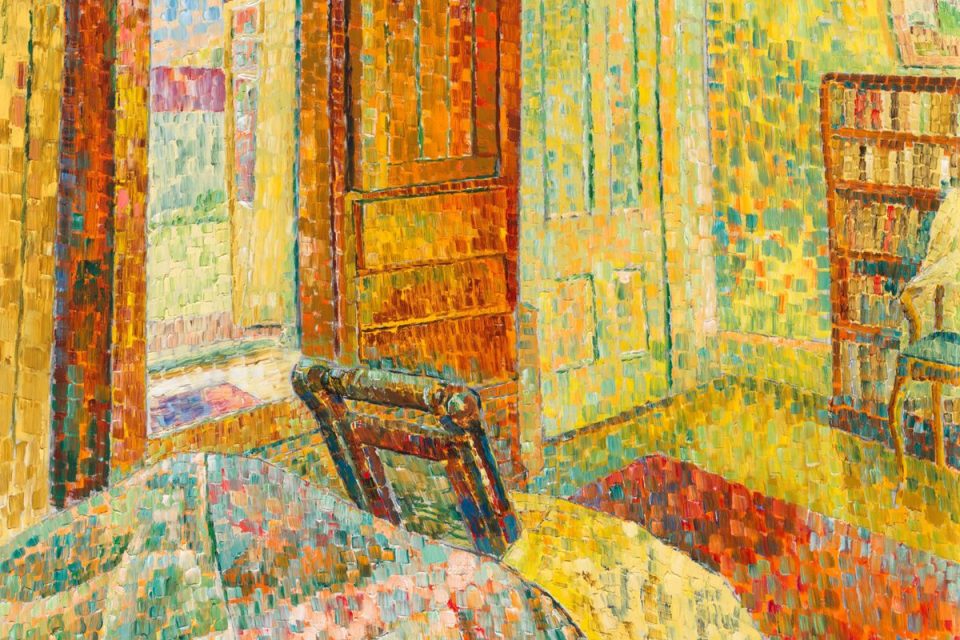

Olive Cotton’s Teacup Ballet is a 20th Australian art icon. Photo: NGA

Artists including Spowers, Syme, Preston and Black embraced relief printmaking with an eye on dynamic compositions and traditions of Japan. Cotton explored modernist photography, while Cossington Smith and Beckett, from very different perspectives, adopted an intimate perspective and brought a magic radiance to a surrounding well known to them.

One could easily add the names of a dozen other women contemporaries working in related styles – some of them included in passing in this wonderfully contextualised exhibition – to make the point that women artists in the 1920s and 1930s spearheaded the Australian push into modernism.

Spowers and Syme, who had been friends since childhood, studied printmaking with the avant-garde artist Claude Flight in London and were inspired by cubism in Paris. Through the modern medium of the linocut, they brought their dynamic compositions and vibrant colours to Melbourne.

Black conveyed modernist, Cubist-inspired forms into the heart of Sydney and Adelaide, while the wonderful Jessie Traill, inspired by Frank Brangwyn in England and France, created huge and powerful etchings that stood out in the Australian art scene.

Preston, with a mixture of European modernism, Japanese aesthetics and wacky homespun ideas of Australian nationalism in her woodblock prints and vibrant oils, stirred the possum in the Sydney art scene. Cossington Smith grew progressively better with age from her early dynamic compositions to her late glowing images of radiance.

Beckett brought a rare introspective sensibility to a surrounding environment, while Cotton progressively shrugged off the shadow of Max Dupain to make a claim as Australia’s leading modernist photographer.

The depth of the NGA collection and the outstanding level of scholarship assembled by the NGA curatorial team, consisting of Dr Deborah Hart, Elspeth Pitt, Dr Shaune Lakin, Dr Sarina Noordhuis-Fairfax and Deirdre Cannon, means that we are seeing some of these well-known artists with fresh scholarly insights through familiar and previously unknown work.

Throughout the exhibition, there is a constant heightened visual excitement with surprising connections and unexpected juxtapositions.

I suspect this will be viewed as a landmark exhibition in Australian art that documents the arrival of ideas of modernism in Australia through a group of pioneering women artists.

Know my name; Making it Modern is at the National Gallery of Australia until 8 October, open daily between 10 am and 5 pm.

Sasha Grishin is a critic, art historian and writer currently completing a history of contemporary Australian art.