Coin designing at the Royal Australian Mint. Photo: James Coleman.

Coins are now somewhat of a novelty from a previous age when you could score a bag of lollies for 20 cents. So up until news broke that King Charles III will replace the effigy of his mother on the ‘heads’ side, you probably hadn’t thought too much about what actually goes into designing a coin.

You’re not alone. Until a few years ago, neither had Lydia Ashe.

“Before this, I didn’t really think about how coins were made,” she says.

“They were just among those things in the world you see and use without thinking about how someone actually designed them, put them together and physically manufactured them.”

In any given year, the Royal Australian Mint in Canberra churns out hundreds of thousands of coins and distributes them through banks and shopping centres. The team behind them are dubbed ‘Minties’, and Lydia is among them, although her actual job title goes something along the lines of ‘coin designer’.

The long-time local was studying sculpture at the Australian National University (ANU) when she heard there were Mintie jobs going. She didn’t get in at first, but she didn’t give up either.

A few years later, in 2012, she was back in the tool room as an apprentice.

“I thought, why not? It’s fun, I get to learn things, I get to use new tools, and I get to make stuff every day.”

Royal Australian Mint coin designer Lydia Ashe. Photo: James Coleman.

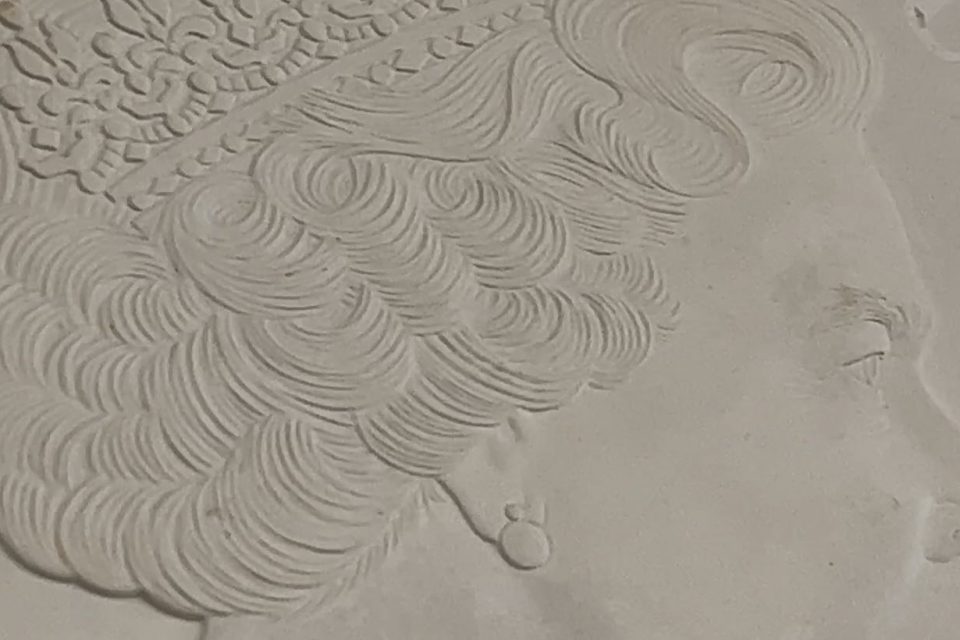

But before you presume there are a lot of microscopes and jewellers tools involved, the coins start out in life roughly the size of dinner plates.

“It’s much easier to work bigger and make it smaller than to try and get all that detail in when it’s so small,” Lydia says.

It’s a very long process. The design concepts are finalised elsewhere and only come to Lydia’s team when the higher powers are satisfied. In the recent case of a coin to celebrate 100 years of Vegemite (with Woolworths), these can include big brands too.

“The product designers will come up with an idea for celebrating an anniversary of something or commemorating a historical event, and they’ll decide what sort of things they want to see on it,” Lydia explains.

“They’ll give us a design brief which may have very little information, or it might have heaps describing exactly what they’re after.”

It’s the job of Lydia’s team to make it all work.

“We have to come up with a pleasing design with all those things, so we’ll research, do drawings, put different features together and talk about it with the developer and the technical engineers involved in the manufacturing process.”

Digital designs are created and then painstakingly carved in plaster by an extremely fine-toothed cutting machine. Other individual elements are sculpted by hand in either plaster or plasticine, while another laser machine can scan these to create digital files.

The moulds are progressively shrunk down to something hardy enough it can be used to create thousands of coins, with some tricky decisions along the way.

“You have to look at many different technical aspects, like if a design gets too close to the rim, it will be hard to mint,” she says.

They also have to think about how tiny markings will translate because a sharp edge on something the size of a dinner plate won’t appear the same on something that fits on the tip of a finger.

“You really have to keep in mind what is going to show up when it’s really small and also the limitations of the machines that cut the coins.”

Mass production capability means some designs take even longer, like the effigy of King Charles III.

“We’ve had Queen Elizabeth II for so long, we knew how it worked and how it coined, but we can’t be having problems while we’re trying to make millions of coins, so there is a lot of testing to make sure the new design works as we want it to.”

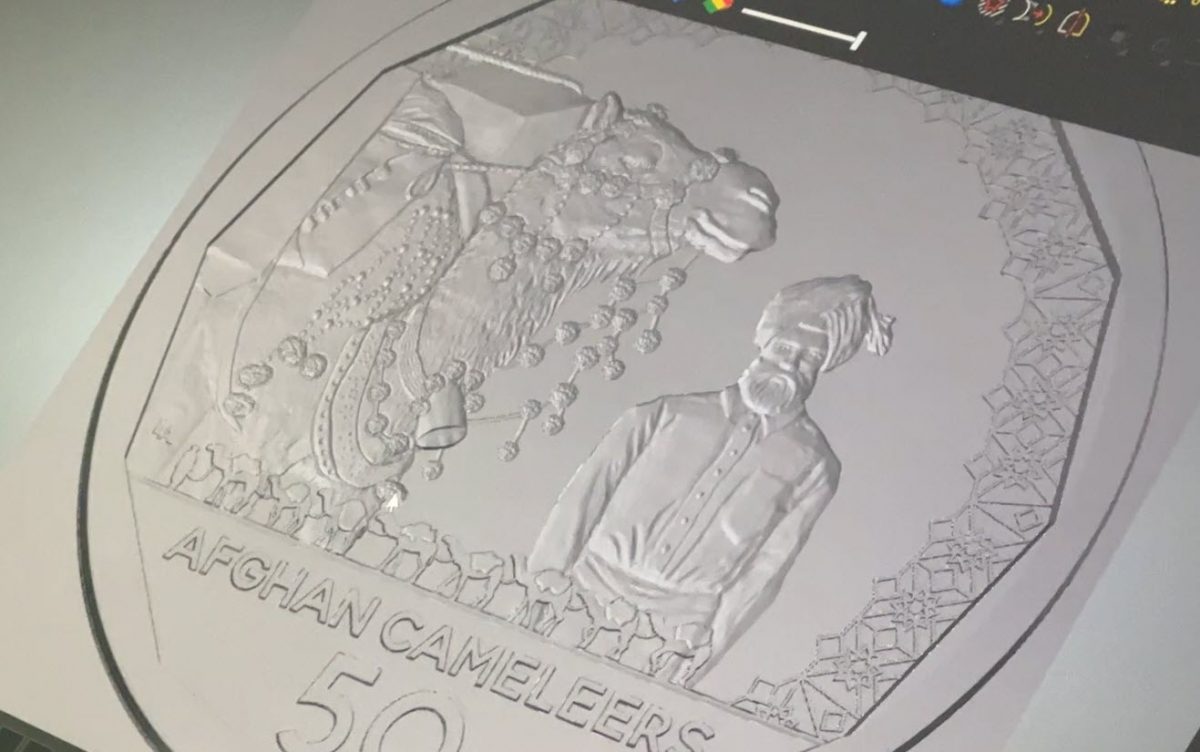

Lydia’s design for the Afghan Cameleers 50-cent coin made it into production in 2020. Photo: James Coleman.

For this reason, Lydia has only seen a few of her coins released over the years, chiefly the Afghan Cameleers 50-cent piece in 2020.

“It takes so long to go from concept to actually minting, so I haven’t had any of my recent designs released yet,” she says.

As for a favourite coin design, Lydia’s vote goes to the classic one-cent to 50-cent coin series, designed by Stuart Devlin before entering circulation in February 1966.

“They’re not super accurate, but they’re pleasing to look at in the form of a coin.”