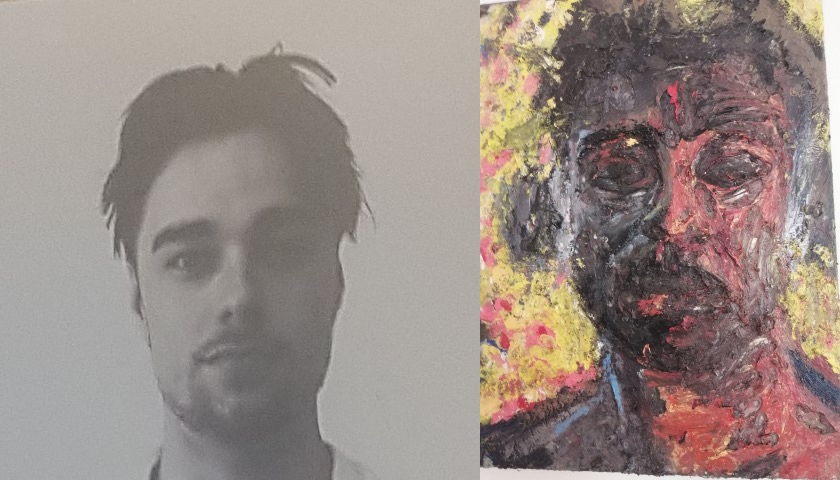

Ravi Madan and a self-portrait which was posthumously submitted to the Archibald Prize in 2021. Photo: Supplied.

CONTENT WARNING: This article discusses suicide and mental health issues.

Ravi Madan was a talented artist who was, as one friend put it, “tormented by demons”.

The caring, gentle young man who died by suicide in April last year is paid tribute to by friends and family on a Facebook page who share his artwork.

For two-and-a-half years before his death, his increasingly desperate parents struggled to get him the help he needed, coming up time and time again against a system his mother, Leigh Watson, and father, Ashish Madan, say wasn’t fit for purpose.

“We were so alone and frustrated,” Leigh said.

“On the night he died, we made a firm decision that other young adults and their families should not suffer the same fate.”

Leigh Watson and her son Ravi. Photo: Supplied.

Ravi first became unwell only one unit short of completing his university studies.

Despite being prescribed medication for anxiety and depression, by November 2018, he was hospitalised following his first suicide attempt.

He was then taken by police to Canberra Hospital where he was admitted to the Short Stay Mental Health Unit. But apart from a few family meetings, which Leigh says felt more like “interventions”, there was no follow-up aside from a visit the day after he was discharged.

That visit was only because his parents had pushed for it.

In the weeks and months following, Ravi wouldn’t let his parents help him seek support. They struggled to do anything about it, given medical professionals’ concerns about privacy as their son was over the age of 18.

This became a regular pattern.

In 2019, Ravi accepted his parents’ offer of help.

They were unaware of the private facilities available in Canberra, so they had him admitted to the Northside Group Clinic in Sydney where he stayed for three weeks. In 2020, his family enrolled him in more support programs, including with a counsellor he saw weekly.

But his parents say now it was obvious he was noticeably unwell throughout this period and could not hold down a job, socialise or live independently.

By September, things had degraded to the point Ravi had to be taken to Canberra Hospital once more due to suicidal feelings. This time, his parents did not want him to be released as they knew he was now very unwell, but they say they did not have a say in the matter.

A month later, he attempted suicide again but was found in time by police. He was then once again taken to the Canberra Hospital emergency department but released shortly afterwards.

Following this, his parents tried to, in their words, “take more control” of Ravi’s mental health care. They found it difficult to get him into a residential care program in Canberra but were never provided with a clear reason as to why this couldn’t happen.

Eventually, they asked around and found out about Hyson Green at Calvary Hospital where he stayed for three weeks.

In the months following his release from this facility, Ravi’s condition deteriorated rapidly.

His parents also sought repeatedly to have Ravi assigned a case worker of some kind to get individualised support for their son. Their progress in this area was largely futile.

Over almost three years of fighting for their son – who they were financially responsible for – Leigh and Ashish say medical practitioners simply wouldn’t communicate with them.

“We had no communication on what his state of mind was and what the risks were of him making another [suicide] attempt,” Leigh says.

“We had an angry, sad, non-communicative and very unwell young person in our home.

“We were not given any information on how to get him effective treatment and no information or support to navigate the quagmire that is the Territory’s mental health system. At no time did we receive any acknowledgement that we were his carers nor that we were in the middle of a very challenging, traumatic and distressing time.

“It was like someone had sent us a ticking time bomb with no instructions on how to diffuse it.”

They also say the discharge policies are not clear.

At one point, Ravi was discharged only 48 hours after a suicide attempt and was not provided with any follow-up support.

Leigh and Ashish welcomed the ACT Government’s commitment earlier this week to provide a follow-up service to support young adults following a suicide crisis or attempt.

But they are calling for more.

They say a caseworker must be provided before a young person leaves the hospital to build a relationship.

Furthermore, following their own experience, they say the family or carers of the young person should be provided with a family peer support program worker to support them.

And neither Leigh nor Ashish are going to stop fighting until those recommendations are implemented.

In a statement, the ACT Government said it appreciates feedback from people with lived experience on how they can deliver early intervention and aftercare services across the mental health system.

“Every life lost to suicide has ripples throughout our community, and our thoughts are with the families and friends of those we have lost,” they said.

The government said a comprehensive assessment is conducted of anyone who presents to the health system with suicidality.

This is followed by them being able to access a “number of services” which the government said work with community partners to deliver follow-up care following hospital discharge, broader referral pathways, proactive outreach and psychosocial supports.

The Territory Government said it is working alongside the Commonwealth on universal aftercare services to support individuals following a suicide attempt or crisis.

If this story has raised concerns for you, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14. If someone is in immediate danger, call 000. Information and support for anxiety, depression and suicide prevention are available through Beyond Blue.

A list of child and youth mental health services in the Territory is available online.