Autumn in Canberra can be spectacular. Photo: Michelle Kroll.

To many of us, Canberra is synonymous with trees. In fact, some would argue the Bush Capital looks its best when sporting autumnal colours in its streets, parks and laneways.

But that wasn’t always the case.

In 2015, forest canopy covered 19 per cent of the ACT’s urban area and by 2045 the ACT Government wants to see that hit 30 per cent.

It’s an ambitious target, particularly if you consider that when Canberra was developed back in the early 1900s the site had been badly denuded.

“Black Mountain had been mostly cleared – anything with grazing potential had been cleared,” Canberra University Adjunct Associate Professor Dianne Firth said.

“The site for Canberra was largely devoid of trees.”

Dr Firth researches the landscape heritage of the ACT and writes on the history, theory and practice of landscape architecture, particularly the designed landscape of Canberra.

She is passionate about trees and says you can track much of Canberra’s development through the species used and the way they were planted.

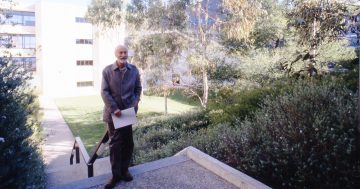

Canberra University Adjunct Associate Professor Dianne Firth researches the landscape heritage of the ACT. Photo: University of Canberra.

“It really goes through phases reflecting who was in charge at the time,” she said.

“Because Canberra’s development has been so orderly, you can see that reflected in what’s been planted.”

When Canberra was in its infancy, it was quickly discovered the trees that grew in Sydney and Melbourne were no match for the inhospitable environment. A government nursery was set up at Yarralumla to test trees that could cope with the ACT’s freezing winters and hot, dry summers.

In 1913, Thomas Charles Weston took on the job of repairing Canberra’s denuded landscape. One of his first outlays was fencing to allow the natural regeneration of hill tops in the ACT.

“If you go to the top of Black Mountain you can see the mother trees and the generations of trees that have sprung up around them,” Dr Firth said.

“You can go to suburbs like Reid, a heritage precinct, and you can also see trees that were planted in that early period.

“If you go to Haig Park you can see the conifers that were planted as a windbreak for the city.”

In the early days, trees were planted in Canberra’s streets to make the tough climate more liveable. Deciduous trees were planted to allow the light in, evergreens to protect. Then came the realisation trees could do much more than that.

When Weston retired in 1926, Alexander Bruce took his place as superintendent of Parks and Gardens and saw the potential plants had to add beauty and allure to the national capital.

“Alexander Bruce was the one who wanted the city to look pretty in spring and autumn,” Dr Firth said.

“He put in the flowering trees that he knew would bring people to Canberra.

Some Canberrans have a love-hate relationship with trees. Photo: Michelle Kroll.

“If we look back at the writings from that time, they were quite picturesque. Some of the politicians were poets.”

In 1935, Bruce was replaced by veteran nurseryman John Hobday whose career spanned 30 years at Yarralumla Nursery.

He continued with maintenance of the trees until 1944 when Lyndsay Pryor took over as Superintendent of ACT Parks and Gardens and established the Botanic Gardens in Canberra.

“In the 60s and 70s, we saw a different way of planting,” Dr Firth said.

“Aranda has lots of curvy streets, all planted with eucalypts. Eucalypts became a symbol of nationalism and there was a wattle frenzy.

“Most of that shrubbery only lasts 10 to 15 years though, so a lot of the eucalypts that were planted took over.”

With more than 770,000 trees in streets and urban open spaces across the city, Dr Firth believes Canberrans still have a love-hate relationship with trees, but their proliferation is accepted as the norm.

“But the way we live has made it harder to plant trees,” she said.

“The newer suburbs have much smaller blocks. Planners try to keep existing trees, but the stress placed on them can cause them to die later.

“Some look at their nuisance value without seeing the benefits of trees. We have to consider when tree health declines, when is the best time to replant.

“Every tree can be a problem, but every tree also provides a benefit. It’s a balancing act,” she said.