Man-uka or Ma-nuka? That is the question . Photo: Michelle Kroll.

It’s Ma-nooka – just like the honey, right?

Wrong.

Marn-aka – like the Queen said, then?

Probably also wrong.

But however you choose to pronounce Manuka, there’s a bigger question: how did an inner Canberra suburb end up with this name anyway? (And following comments from Riotact readers, is it really a ‘suburb’? But that’s for another day.)

Pared back to its roots, ‘manuka’ is the name the Maori people gave to a small tea tree with nectar, which has risen to fame through Manuka Honey. It’s native to New Zealand but also pops up here in Australia – in Tasmania, Victoria and NSW.

Nick Swain is secretary of the Canberra District and Historical Society and also co-authored a book with Meryl Hunter called Manuka: History and People, 1924-2014. He says the Canberra connection dates back to the very first plans for the Australian federation.

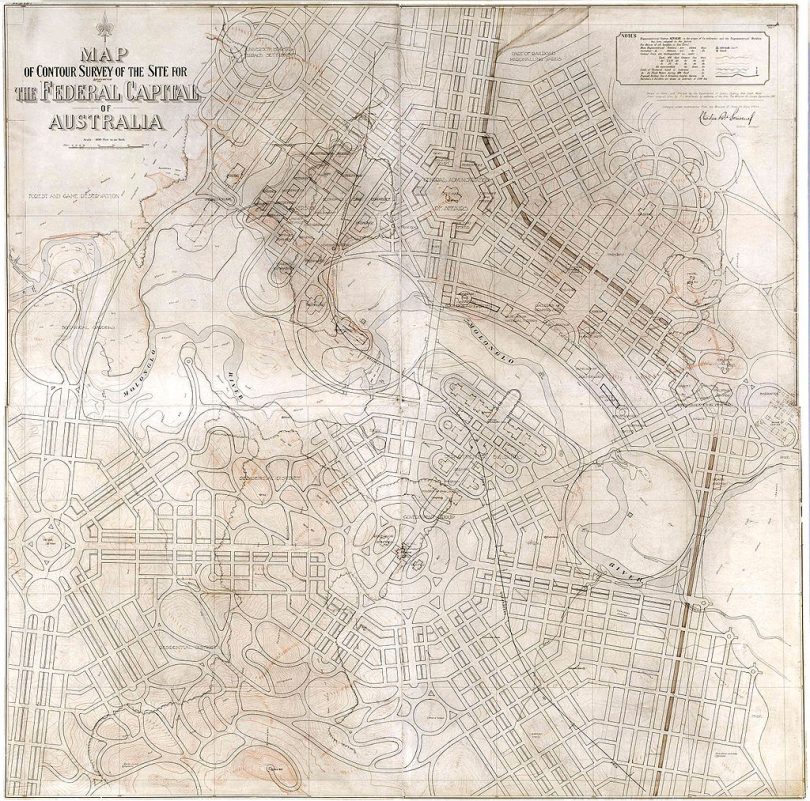

The map of Canberra drawn by Charles Scrivener, with Walter Burley Griffin’s plans over the top. Photo: Public Domain.

“In the early 20th century, it was hoped New Zealand might join Australia as another state,” Nick explains.

“Canberra’s architect, Walter Burley Griffin, devised several avenues coming off State Circle like spokes on a wheel, each one taking a name from the capital cities.

“So we have Sydney Avenue, Melbourne Avenue, Brisbane Avenue, Adelaide Avenue, Hobart Avenue and Perth Avenue.”

The stretch between State Circle and Kingston (or as it was known then, Eastlake) was designated ‘Wellington Avenue’, after the name of New Zealand’s capital.

“Canberra Avenue was where Limestone Avenue is today,” Nick says.

Each of these avenues was meant to terminate in a park named after the first governor of the relevant state, but when Griffin arrived in Australia, there were a few changes to his plan.

“The local development board was anxious that some sort of shopping precinct be factored in for the south of Canberra,” Nick says.

“He wasn’t happy about it, but he agreed to adjust his plan.”

It’s not by chance that Telopea Park is linked to Sydney Avenue. The Griffins had a plan. Photo: Halloleo.

While he was at it, Griffin also decided to go with local botanical names for the parks.

Sydney Avenue, for example, ends in Telopea Park (Telopea is the Latin name for the floral symbol of NSW, the waratah). Wellington Avenue ended at Manuka, named after the tea tree (it morphed into Eastlake Avenue beyond there).

By the late 1920s, however, it became clear that NZ would not be coming to the party. Wellington Avenue was dropped in favour of Canberra Avenue. Only two references remained: the Wellington Hotel, where Rydges Capital Hill is today, and Manuka.

However, even in those early days, nobody was quite sure how to say it.

The Canberra Times advised in 1926 that “there is no ‘man’ in Manuka”. The article quoted Mr Waterman, then chairman of the Council of the Boy Scouts’ Association, who said, “The official pronunciation is Ma-nuka”. This aligns with the common pronunciation across the ditch.

A few decades later, in 1965, secretary to the Federal Capital Commission, Charles Daley, wrote in the same paper that the name was still proving “a puzzle to many”.

Manuka was designated to be the shopping district for south Canberra. Photo: Michelle Kroll.

He argued Sir John Sulman, chairman of the Federal Capital Planning and Development Committee, laid down the law in 1921 when he insisted the strong accent be placed on the first syllable.

“Bowing to his authority, we adopted this variation which soon passed into general use,” Mr Daley wrote.

This blows a hole in the urban legend that it was Queen Elizabeth II who, during a royal speech at the Manuka Oval in February 1954, first put the ‘man’ in Manuka.

Mr Daley did mention this pronunciation has often been queried by New Zealanders. So one evening, at a YWCA function, he decided to get to the bottom of it.

“I asked a Maori girl which pronunciation was the correct one, accent on the first or the second syllable,” Mr Daley wrote.

“To my great surprise, she replied ‘neither’ and explained that, like French, the Maori language had few strong accents and that ‘Manuka’ should be uttered with even stress on each of the three syllables, like a ripple.”

So, coming back to the questions at the beginning, it seems both answers are only half wrong.