The ACT has been ahead of the curve when it comes to municipal waste management for almost two decades now. It was the first government in the world to set a zero waste goal all the way back in 1996.

The no waste by 2010 goal may not have been achieved, but we successfully lifted our recycling rates from 40 per cent to more than 70 per cent of our total waste steam – the highest in the country at the time. We also have the lowest litter rates per capita.

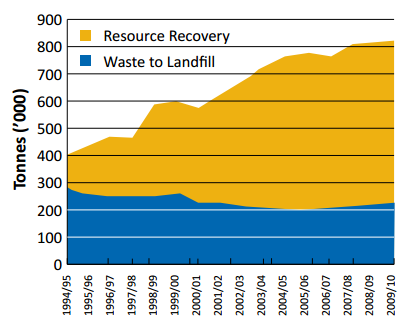

This chart from the ACT government’s updated waste management strategy shows how over the past 15 years the ACT has managed to decrease its waste levels sent to landfill annually.

The same chart also illustrates a real challenge. Our population has only increased by 16 per cent in a decade and a half while the total amount of waste generated across Canberra has grown by over 100 per cent.

In fact, per capita the ACT generates the highest amount of waste in the country. (However, it should be noted that this increase has largely come from the commercial and construction sectors, and not from households.)

The business of recovering and reselling waste products is now a significant money-earner. The most recent national statistics show that waste management organisations in Australia were paid $8.6 billion annually, with $2.4 billion in waste products shipped overseas for processing.

While it is obviously better to recover waste than to leave it in landfill, it is better still not to generate the waste in the first place. Having manufacturing processes that allow continual reuse of its materials is sometimes referred to as a “circular economy”.

For example, in the US the jeans maker Levi Strauss wants to reuse cotton from old garments in new products to eliminate its waste by 2020.

Customers are given a 20 per cent discount when purchasing a new item if they bring in an old garment for recycling. Subaru recently celebrated 10 years of zero-landfill manufacturing of cars, where all waste is either recycled or turned into electricity.

In the construction industry, there is increasingly a shift towards building deconstruction instead of demolition. Deconstruction is a process of taking a building apart with sufficient care so that the materials can be reused and recycled. As disposal charges for building materials increase, deconstruction will become normal.

This encourages innovations in modular, prefabricated building materials that are easy to assemble and disassemble. Reuse rates of 95-100% are typical when fully modular building components are used.

Lastly, no discussion of waste would be complete without looking at the option of a third bin for garden waste (grass clippings and plants) and/or organic waste (kitchen scraps) – a long-time topic of discussion for ACT residents. With around 25 per cent of waste going to landfill coming from residential sources at the moment, there is scope to do better.

A 2011 consultancy found that a third bin for green waste would be largely ineffective since the ACT already recycles more than 90% of its green waste. The same report also found that a third bin for organic waste would be much more expensive ($20m / year) than using dedicated machinery at the landfill to extract organic material from both residential and commercial waste ($8m / year).

With a separate organics bin, on average households will place no more than half of their organic waste into this third bin. So even with a third bin, the regular bin will still contain significant amounts of organic waste that go to landfill.

From this point of view it is regrettable that in 2012 the Greens and Liberals joined together to block the purchase of the specialised equipment required. As a comparatively straightforward way to reduce waste sent to landfill by half or more, it would be nice to see this put back on the agenda.

Are we doing enough to reduce our waste in the ACT? What else would you like to see done?