ACT Bar Association vice president Jack Pappas alleges a ‘cowboy culture’ among police. Photo: ACT Bar Association Twitter.

Veteran ACT barrister Jack Pappas has stood firm over explosive allegations about Canberra’s police following a dip in ACT criminal conviction rates.

Mr Pappas accused ACT Policing of a “cowboy culture” when collecting evidence, which he said led to cases being thrown out.

His comments followed the publication of the latest Productivity Commission data regarding the ACT’s criminal conviction rate, showing it had dropped from around 95 per cent for the five years before 2019 to 65 per cent for 2019-2020 and 66 per cent for 2020-2021.

When questioned by Region Media over why the blame lay with police, the ACT Bar Association vice president said you had to “look at the variables”.

“We have a first-rate Director of Public Prosecutions and staff. You couldn’t lay any fault or blame at their feet,” he said.

“You [also] can’t say [any of our magistrates are] a dud … My own experience is very often [cases] get to a hearing and you discover that police have been a bit naughty, they’ve cut corners and done things inappropriately.”

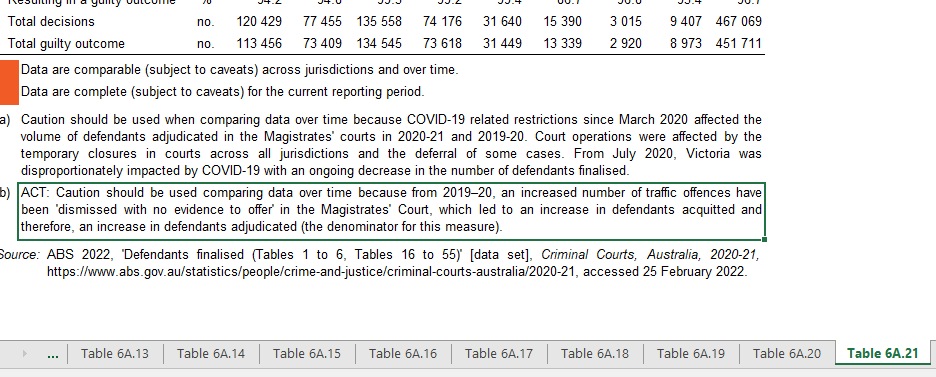

Mr Pappas acknowledged a caveat in the Productivity Commission report that the 2019-2020 results had to be treated with caution as during that time “an increased number of traffic offences have been ‘dismissed with no evidence to offer’ in the Magistrates Court, which led to an increase in defendants acquitted”.

However, he felt that didn’t fully explain the drop.

“I went through a checklist of what might be [the reason] and one variable raised was the way cases are prepared,” Mr Pappas said.

Caveat on guilty outcomes for defendants’ table in the latest Productivity Commission report. Image: Productivity Commission.

He said while police may not necessarily be “intentionally” gathering evidence in an illegal way, it was still a serious problem.

“More police [now] are ill-trained and cut corners … I’m not saying they do so to make issues, but they’re not well supervised,” Mr Pappas said.

“Now you have young police officers who may have been there for 18 months who are now Acting Sergeants. How can they run a proper investigative team if they themselves are inexperienced?”

Mr Pappas acknowledged police were subject to both internal and external scrutiny but questioned how effective such procedures were.

He also claimed police had a “habit” of overcharging and continuing to gather evidence while cases were before the courts.

“[This] results in almost an outcome bias in evidence gathering,” Mr Pappas said.

“It creates a real tendency to only pursue evidence that supports the charge rather than the full picture.”

He said he made these comments not to be a “nemesis of police” but hoped it would spur the force to fix the issues.

“I’ve had many colleagues say ‘well done’, that it was about time someone said something,” Mr Pappas said.

Veteran barrister Jack Pappas stands behind his comments about ACT Policing. Photo: ACT Bar Association.

ACT Policing deputy chief police officer Peter Crozier invited Mr Pappas to speak with him directly about his concerns.

“I reject the assertion that our policing culture is leading to failed prosecutions in our courts,” he said.

“In the last financial year, 93.1 per cent of all matters brought before the court were subsequently proven through respective court processes.”

Mr Crozier insisted ACT Policing’s review and training procedures should reassure the community and courts about the commitment of police to avoid errors and misjudgements.

“The commitment to integrity and adherence to appropriate legal doctrine form the cornerstones of our values and our service to the community,” he said.

The police union also slammed the comments.

Australian Federal Police Association (AFPA) president Alex Caruana questioned whether Mr Pappas’ experiences were as common as he claimed.

“Suppose the allegations mentioned by Mr Pappas were so common, I would question why hasn’t media been reporting on these allegations of improper behaviour?” he asked.

“Nowhere else in the country are police officers or any public official subject to more scrutiny than members of the AFP. If what the ACT Bar Association was saying was true, the community would undoubtedly already be aware.”

ACT Policing and AFP members are subject to internal oversight through Professional Standards and external oversight by the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity (ACLEI) and the Commonwealth Ombudsman.

“These bodies look at a whole range of different conduct, including things that happen at work, such as the use of force and the exercise of police powers, but also incredible scrutiny of their personal lives as well,” he said.

“Police officers are humans just like everyone else, and mistakes can occur, but these are few and far between. Members of ACT Policing, and more broadly, the AFP, are subject to the most rigorous oversight of any Australian police officer, politician, or public servant.

“I question how many Bar Association members would be able to pass the same rigorous standards expected of members of the AFPA, including integrity gateways, regular drug testing, needing to declare association and financial gains?

“It appears that there has been an over-simplification on the part of [Mr Pappas] and no real critical analysis of other factors at play,” he said.

The AFPA rejected the suggestions officers disregarded legal processes and that police culture led to failed prosecution.

“Ultimately, the ACT’s guilty rate is determined by the judicial system. ACT Policing doesn’t determine if someone is ‘guilty’ or ‘innocent’; that is a matter for the judiciary,” Mr Caruana said.

“Likewise, [Mr Pappas’s] view does not take into account other factors, such as the DPP being responsible for the prosecution of those charged.”

An ACT Bar Association spokesperson said Mr Pappas’ statements “are not reflective of the views of the entire Bar Association and should not be interpreted as such”.

We give the impression that paying board members thousands of dollars in “allowances” and… View