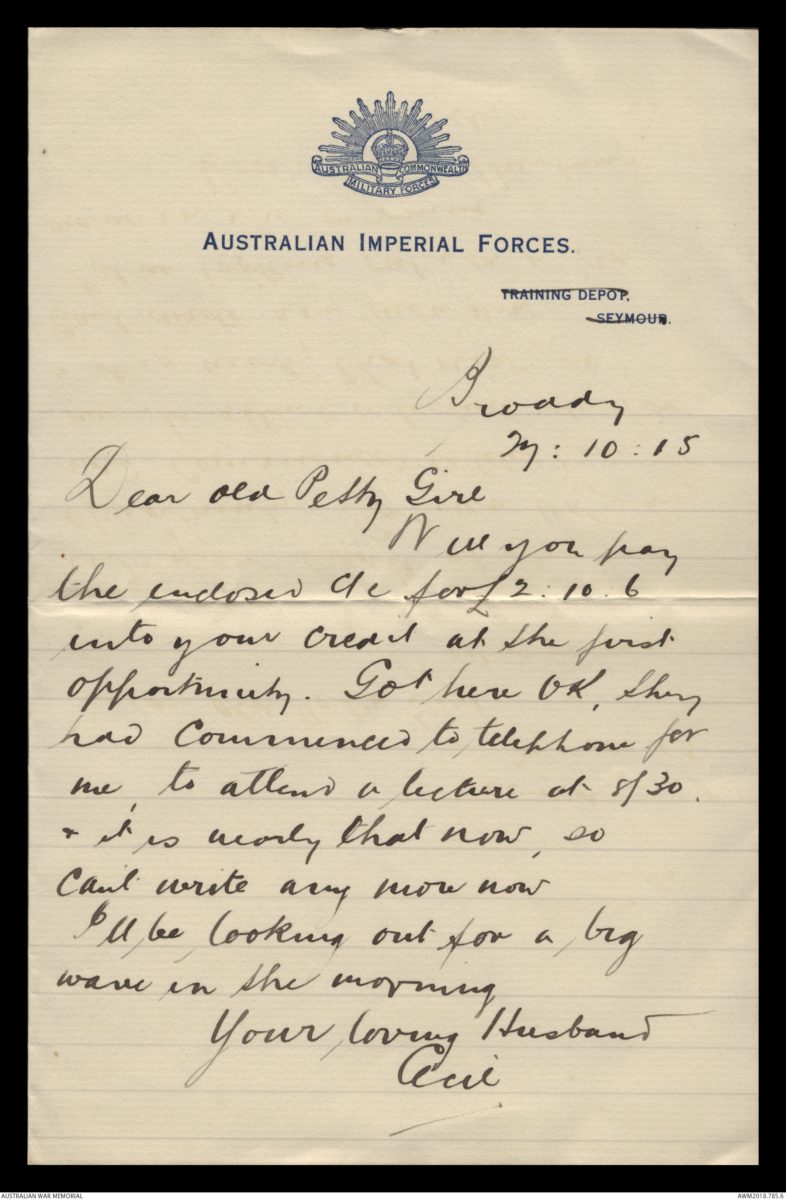

Cecil Mills’ letter to his wife in October 1915, written to his “Dear Old Petty Girl”. Photo: Australian War Memorial.

They are the most personal of letters: one written from a husband and father who was never going to come home from the war, others from family at home whose words injected lifeblood into those at the front.

The man who didn’t come home from the war was Second Lieutenant Cecil Beaumont Mills, born in 1881 and originally from Shellharbour in NSW. He saw action on the Somme, but was killed on 4 August 1916 during the battle of Pozieres.

In a letter to Cecil’s wife, a colleague wrote: “… it was while [he was] running across no man’s land to give instructions to some of his men when he was caught by machine gun fire and … it was instant”.

Cecil, who is commemorated on the Villers-Bretonneux Memorial in France, left a son, John Burne Mills, born in 1915 – a son who was never to know his father.

In later years, John went to France to see where his father had served and died for his country and later donated the family letters to the Australian War Memorial (AWM) along with his letters describing what it was like going to France to walk in his father’s footsteps.

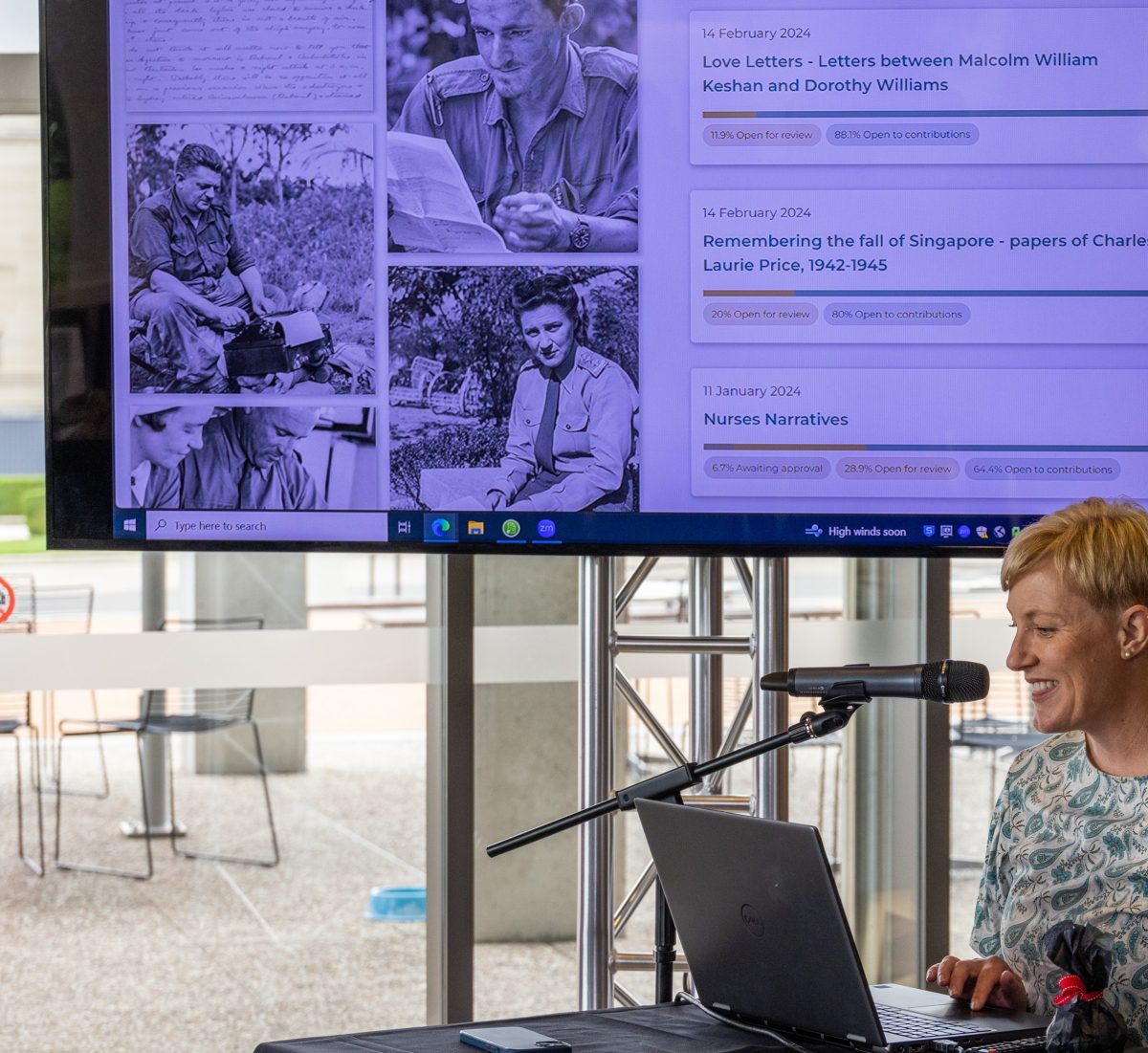

The Mills family correspondence is part of a collection of hundreds of thousands of letters, diaries and other ephemera in the AWM collection to be digitised in a new project announced this week called Transcribe.

Head of Digital Experience at the AWM, Terri-Anne Simmonds, said the project allowed the AWM to, using the most modern technology, ensure that these fragile pieces of paper – ephemeral material that was never meant to last – would remain safe for future generations to read about.

“One of the wonderful things about this website is that it is so easily accessible,” Ms Simmonds said. “You can look up close at these documents without compromising their fragile nature.

“Eighty or 100 years ago, people never thought that others would be interested in reading what they wrote. But in many cases, it is the only record of what happened, of how they thought, and it’s a first-hand account which is increasingly rare.

“Family members have been very generous in sharing their stories with us.

“We are so fortunate to be in a position to bring the past and future together using technology, and make it live.”

She described reading the letters as like “travelling back through time”.

“But many of them are also heart-breaking,” she said. “Some of the letters we have were written to wives, letters that, if they died, were the last piece of correspondence they had.”

She said some of the letters had been acquired by the AWM, many were donated whilst others were surprise packets – found in an old suitcase or in other material given to the AWM.

Working with the AWM’s archivists, the digital team helped curate the vast collection of letters for processing, sorting the material into different batches and topics, to make them more accessible.

Head of Digital Experience at the AWM, Terri-Anne Simmonds shows off the new Transcribe website. Photo: Australian War Memorial.

Ms Simmonds said the AWM was calling for volunteers to help transcribe some of the letters so they could go online telling the full story.

“Because some of these letters were written in place like prisoner-of-war camps and front-line trenches, and are often written in cursive script, they are not always easy to decipher,” she said.

“This new website, encourages volunteer transcribers in assisting all Australians by turning these thousands of handwritten documents into digital text – which are then able to be searched and made more discoverable by the public on the Memorial’s website.”

More information for people interested in helping to transcribe the letters is available on the AWM website.