A Virginia class SSN nears completion in the Electric Boat shipyard in Connecticut. Photo: General Dynamics Electric Boat.

No matter how many Australian, British and American politicians try to sugar-coat it, the ongoing difficulties in US and UK submarine programs and industry are adding substantial risk to Australia’s nuclear-powered submarine ambitions.

The US Navy currently has a requirement for 66 nuclear-powered attack submarines, or SSNs, but currently has about 50 in service. Further, that number is dropping as its older Los Angeles class boats are decommissioned and production of current Virginia class SSNs fails to achieve the required rate of two per year to keep up.

On top of that, the US Navy is developing its next ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) – the Columbia class – to replace its aging Ohio class ‘boomers’. Columbia production is already underway – in those same shipyards – and is due to accelerate over the next few years.

In the UK, the Royal Navy’s Astute class SSN program is nearing completion but is also several years behind schedule. While discrete elements of the UK’s own next-generation Dreadnought class SSBNs are already being built, that program is still developmental, and shipyard integration and production can only commence once the Astute line is completed.

In order for the US Navy to be able to transfer a used Virginia class submarine to the Royal Australian Navy in 2032 and maintain its own force requirements, its two shipyards need to be producing new Virginias at the rate of 2.33 boats per year, on top of its Columbia SSBN requirements. They’re currently running and have been stuck at a rate of about 1.3 for several years.

The reduced rate is due to disruptions in the shipyards’ supply chains caused mainly by low unemployment levels and workers moving away from manufacturing into higher tech or service industries.

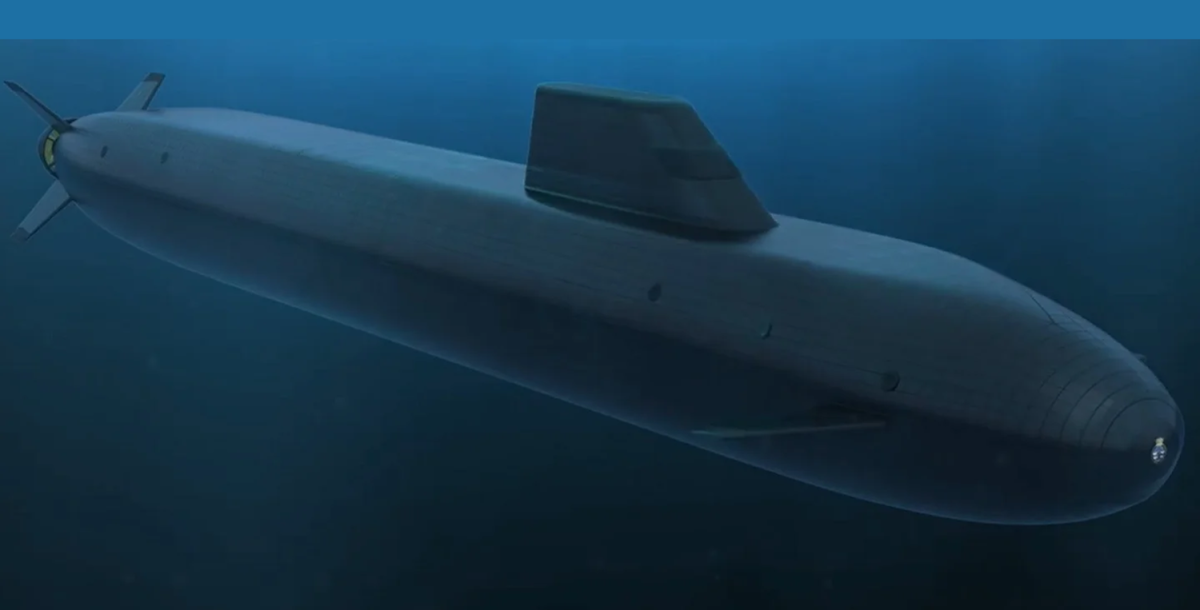

The SSN-AUKUS is expected to take design cues from the UK’s new Dreadnought class SSBN. Image: BAE Systems.

The UK’s Defence Secretary has blamed low production rates on the ‘peace dividend’ of reduced defence spending which western governments repeatedly dipped into following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. He said efforts to turn that around have only really ramped up in earnest in recent years.

“We saw Defence spending fall, and that happened in the United Kingdom as it happened elsewhere,” he told media in Canberra.

“The peace dividend was taken once, twice, three, four times, and you can’t carry on doing that. We recognised that a number of years ago, and we’ve been increasing our defence budget.”

But a defence budget is not something you can just “increase”. In order to spend more money, you need to have sufficient people in place to define requirements, to design, test and develop capabilities, to draw up and execute commercial agreements to buy the capabilities, to build the capabilities, and then to operate and sustain the capabilities.

So, unless your country is in a total war or Cold War situation like the world faced from the late 1930s through the 1980s, it is not feasible for an economy to just ‘flick a switch’ and instantly have the necessary resources in place to accommodate an increase in defence spending.

Regardless of its merits, Australia has seemingly made a good start on its ambitions to acquire SSNs. It has acquired land for a new shipyard at Osborne in SA and has started working with educational institutions to develop appropriate trade courses.

It has also placed Australian sailors in US and UK nuclear power schools, shipyards and Navy exchange postings, and has been approved to send Australian industry workers to the US and UK to start learning how to build and sustain SSNs.

The stern section of the US Navy’s first Columbia class SSBN was delivered to Electric Boat in January. Photo: General Dynamics Electric Boat.

And it has announced that ASC and BAE Systems will form a joint-venture to build the SSN-AUKUS submarines, and that ASC will sustain the Virginia and SSN-AUKUS boats in service.

On top of that, Australia has committed more than $9 billion to invest in US and UK shipyards and supply chains to try to relieve their bottlenecks. While this seems like a lot – and it is – it is comparatively small change when compared to the $368 billion Australia is expected to spend on acquiring and operating SSNs over the next 30+ years.

But it remains to be seen whether there will be any return on that huge investment. Spending money doesn’t miraculously and instantly produce people to be trained to build submarine components – it’s going to be a long, drawn-out process.

What guarantees does that investment give Australia that, if the US fails to achieve its desired build rate, there will be a Virginia class SSN flying the White Ensign in 2032? And what guarantee does it give us that the SSN-AUKUS program will be rolled out on time?

Of course, there are none.

Original Article published by Andrew McLaughlin on PS News.