The ACT’s tallest tree measures 63 metres high. Photo: ACT Government.

The honour of tallest eucalyptus tree in the world goes to the ‘Centurion’, located about 80 km southwest of Hobart in Tasmania.

The Swamp Gum towers 100.5 metres high according to the latest measurement, which also makes it the tallest hardwood tree and tallest flowering plant in the world.

But to mark the International Day of Forests on 21 March, the ACT Government’s Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate (EPSDD) highlighted our own competitor.

It doesn’t have a nickname yet, but there’s a Mountain Gum (Eucalyptus dalrympleana) that’s been growing in a remote part of the Namadgi National Park for an estimated 400-plus years. It measures 63 metres tall, and 6.5 metres around its base.

To put that in perspective, the tallest trees we’ll see in urban ACT top out at around 40 metres high – or slightly taller than the light towers at Manuka Oval.

These include the Ribbon Gums and Flooded Gums in the rainforest walk at the National Botanic Gardens, a stand of planted eucalypts near Clunies Ross Street in the Australian National University (ANU) and some Eurabbie (Eucalyptus bicostata) in Telopea Park.

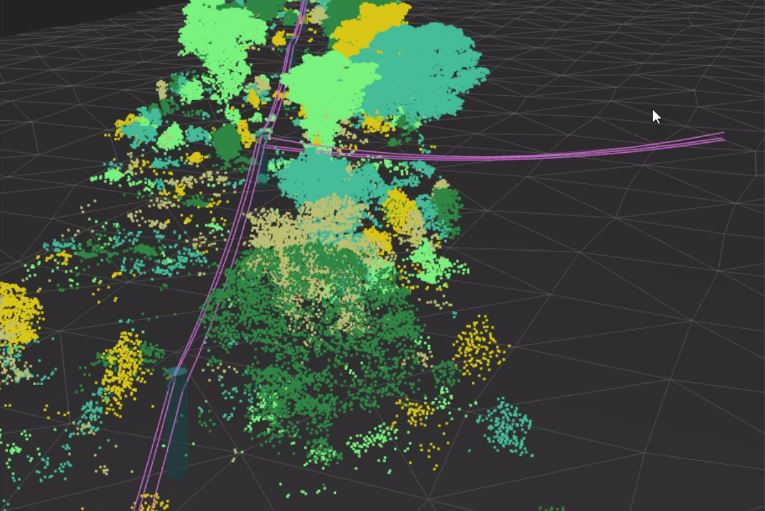

Area manager Oliver Orgill says the ‘new’ big boy was discovered during a bushfire-fuel mapping project with the ANU in 2016. The project employed ‘Light Detection and Ranging’ (LiDAR) radar technology to gauge the height and coverage of the ACT’s tree canopy.

The Mountain Gum, jutting straight out of a steep mountainside, stood out like a sore thumb.

“It’s quite a bit taller than the surrounding trees in the Brindabella Ranges, west of Bendora Dam, in quite a remote part of the park,” Mr Orgill says.

“It’s not easy to get to.”

Images generated by LiDAR are accurate down to the centimetre. Photo: Evoenergy.

The estimated age of the tree is based on a sampling of other trees in the area. Over the past four centuries, it has survived heavy logging projects that commenced in the area in the 1930s, followed by at least two bushfires – one in 2003, where it was mildly burnt, and most recently, in 2019, where it escaped unscathed.

The EPSDD says these events may have actually helped the tree survive, by killing off its competition for resources.

Rangers haven’t visited the site for several years but, as far as they know, it’s still “surviving and thriving” and a variety of native species, including Greater Gliders, Yellow-bellied Gliders and Powerful Owls, nest in its hollows.

“These big old trees are so important for a whole range of species, who need them for habitat,” Mr Orgill says.

Tree hollows are the result of weather damage, branch shedding, insect attack, sped up by the work of strong-billed cockatoos and galahs.

They typically only form in trees over 120 years old, and over the past century – as land has been cleared to make way for development in the ACT – the number of these trees has faced a dramatic decline.

“Competition for suitable nesting hollows is fierce, and birds such as superb parrots, that migrate to the ACT each year, must work extra hard to compete with our resident parrot community for nesting hollows,” the EPSDD says on its website.

This is why the government restricts, “as far as possible”, the clearing of mature eucalypts over 50 cm in diameter, mature native trees containing nest hollows, and other native trees that have reached “approximately 67 per cent of their maximum diameter”.

It also promotes “retention of standing dead trees wherever possible”.

A variety of native species use tree hollows as nest sites. Photo: Eurobodalla Shire.

The dead trees that have to removed for safety reasons often end up in the nature reserves, “enriched” with carved hollows and artificial bark and monitored for how they attract wildlife.

Mr Orgill says these programs have “clearly demonstrated benefits to species recolonising those areas”.

“We are putting in effort to restore missing habitat features – like hollow logs and fallen timber – to provide homes for a whole range of species – everything from insects to reptiles to mammals and birds – to give them a real kickstart.”

Check out the ACT’s other big trees on the National Register of Big Trees.