Head of the AWM’s Research Centre, Robyn Van Dyk, and president of the ACT Branch of the RSL, Kimberley Hicks, look over some of the collection at the Australian War Memorial. Photo: AWM.

They are the first-hand accounts of how our soldiers felt at the end of World War I. From the relief and joy of some to the despair and non-belief of others, the stories come straight from the heart – and the vast vaults of the Australian War Memorial (AWM) collection.

These eyewitness accounts, as recorded in letters and diaries, have been digitised by the AWM and are now available online for everyone to read as Australians mark Remembrance Day today, 11 November.

Back in the 1920s, when the AWM was establishing the national collection, it wrote to families of soldiers who had died in the war, asking if they would be willing to donate diaries or letters. Today, there are hundreds of thousands of items – ranging from a one-page document to a diary with hundreds of pages – all being digitised so the stories live on.

Many of the soldiers kept the diaries on their person, often in their pocket, close to their heart, to record what was happening, be it the daily routine or the desire to be almost anywhere else. The documents tell first-hand what life was like for these soldiers, with some showing only too graphically what life was like – from a bullet hole to bits of gravel.

Head of the AWM’s Research Centre, Robyn Van Dyk, said the diaries and letters offered an intimate insight to the globally significant day that is 11 November commemorating the Armistice of World War I, signed at 11 am on 11 November, 1918.

“The memorial has a multitude of original letters and diaries that express how people felt about the signing of the Armistice and the war coming to an end,” Ms Van Dyk said.

“Many of the letters and diaries on the memorial’s website record how people reacted to hearing of the end of a very long and horrific war.

“What we wanted to know, what we wanted the diaries to show people today was how these men felt back then, what the war really meant to them.

“Nothing is censored. We publish warts and all.”

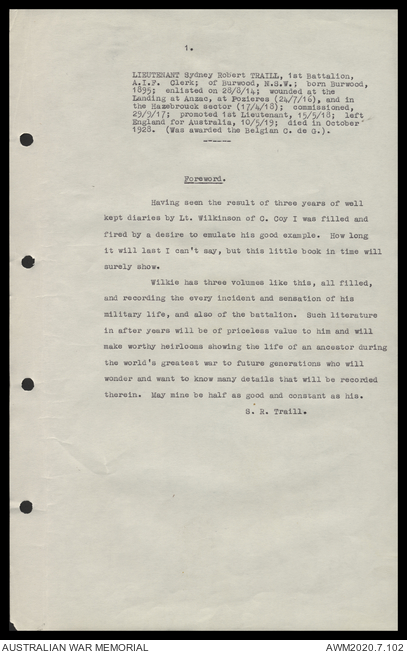

The first page of Lieutenant Traill’s diary, as typewritten by the AWM after the war because his mother could not part with the original. Photo: AWM.

Although many took part in celebrations on 11 November, 1918, not everyone was jumping for joy.

In his diary, Lieutenant Sydney Traill wrote on that day: “It was officially announced late tonight that hostilities have ceased as from 11 o’c a.m today. We knew early in the morning, though. No one displayed the slightest enthusiasm and it doesn’t matter a tuppeny dump to me now, whether it goes on or not, the war has done its worst for our family.”

Lieutenant Traill had reason to be bitter. His brother-in-law didn’t come home.

Ms Van Dyk said when the AWM wrote to Lieutenant Traill’s mother back when it was establishing the national collection, she couldn’t let her son’s diary go, it was too emotional.

“With Sydney Traill,” she said, “who was a Gallipoli veteran, we only have a typewritten copy of his diary. That’s because his mother said she couldn’t part with the original handwritten one. Later the memorial asked if we could borrow it, so we ended up typing it all up and we returned the original to his mother.”

But for 18-year-old Australian Private Gallwey, it was the best of news. Ms Van Dyk said research showed he was taken off the front line and moved into Signals, which could well have accounted for his more optimistic response to the end of the war.

“London has gone mad and I am intoxicated with joy,” he wrote.

Digitisation of the AWM’s vast collection of letters and diaries is part of a four year-project make it more accessible.

“There are over 14,000 collections that have been digitised including archival records, photographs, films, maps, art posters and objects, all now being progressively published,” she said.

“In the past, people had to travel to Canberra and request to view these items which were only able to be viewed from the Reading Room, but now you can access these historic records from home and unlike paper, you can zoom into the text and bring up the content in detail.

“Personal collections such as letters and diaries give us a deep insight into how many Australians felt … you get a sense of what it was like for those individuals.”

To find more of the digitised letters and diaries, search the AWM website