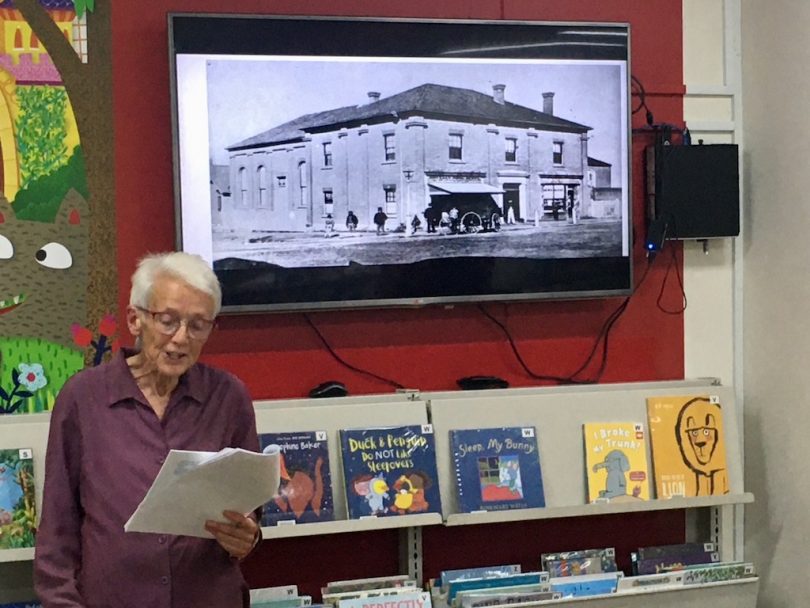

Jennifer Lamb presenting Goulburn’s Rich Artistic History. Photo: John Thistleton.

Much of Jennifer Lamb’s life centres on the arts in Goulburn – and the day is yet to dawn when critics deter her.

Researching for her presentation Goulburn’s Rich Artistic History to coincide with this month’s opening of the Goulburn Performing Arts Centre, Jennifer uncovered years of scathing criticism of the arts, artists and the historic city itself.

Goulburn Regional Art Gallery’s first director, a scriptwriter and actor, Jennifer is a noted historian too. She made good use of the criticism uncovered in her research to spice up an entertaining discourse at Goulburn Mulwaree Library.

Jennifer began by recounting the now-famous Big Merino’s construction in the city’s south in the 1980s. There was a kerfuffle between those who thought the 15.2 metre-high ram utterly abhorrent and those who thought it a veritable work of art.

“The latter decided to publicly ask James Mollison, then director of the National Gallery of Australia,” she said.

“I don’t know what Mollison thought, but a Canberra Times commentator, Robert Macklin, pronounced that it was impossible to include art and Goulburn in the one sentence.

“But I think you can – and must.”

Jennifer then recounted the history of the First Nation’s tribes, who shared stories through song and dance while meeting along the junction of Goulburn’s two rivers.

She also recalled the city’s earliest European history, when it was a little bark-roofed frontier-town.

“The place was ripe for a bit of culture,” Jennifer said.

Nineteenth-century music groups sprang up in Goulburn – including various formations of the Philharmonic Society, the Romany Musical and Dramatic Club, the Amateur Christy Minstrels, the Goulburn Musical Union and the Goulburn Glee Club. Few survived into the 20th century, let alone the 21st.

The one exception was the Goulburn Liedertafel Society, which was established in 1891 and continues today as the Lieder Theatre Company – the longest-running theatre company in Australia.

Abhorrent or a work of art? The Big Merino has been a divisive tourist attraction since its inception. Photo: John Thistleton.

As the 20th century began, the rise and decline and rise again of the Liedertafel Society played out. In 1908, it purchased a home, known then as Landers Hall, on Goldsmith Street where the current Lieder Theatre stands.

In 1914 the Academy of Music, aka Oddfellows Hall, was bought by JW Nicholson who introduced Goulburn to the revolutionary bioscope, or moving pictures – silent in those early days. He renamed the hall the Empire Picture Theatre.

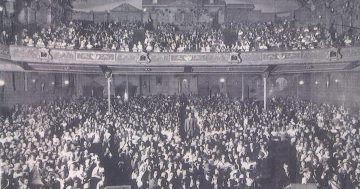

In 1929/30, a new and elaborate theatre was built directly behind the original Oddfellows Hall, which itself was refurbished to incorporate a vaulted Elizabethan ceiling. This new enlarged theatre was justifiably renowned for its massive panoramic sky ceiling – with twinkling stars rotating across it as up to 2400 patrons watched the next new thing – the “talkies”.

The Empire became the Odeon in the 1940s and continued until 1966 when it was converted into a motel, and ultimately demolished in the 1970s to become a shopping mall. Throughout its time as a cinema, the Empire/Odeon continued as a performance venue, such as for a concert by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra in 1951.

The fate of the other major cinema, The Ritz, or Hoyts, was similar. It opened in 1936, boomed until television supplanted cinema, then became Kentucky Fried Chicken in 1972. Some of its seats were recycled to become the seats in the present Lieder Theatre.

Years later, Goulburn needed a large public hall seating some 700 people suitable for performances, especially musical ones, as well as dances and other events. Someone noted that it needed to be modern.

In that year, 1952, the annual festival Lilac Time began and was soon raising funds to build that public hall.

Nicknamed the ‘Grasshopper’ and the ‘Praying Mantis’, it was a well-equipped venue for performances, including eisteddfods and Musica Viva concerts, and was widely used for other activities including dances and wool sales. By the 1990s, the hall was struggling to survive and became the Lilac City Cinema in 1994.

Wrapping up her look at arts in Goulburn, Jennifer touched on Australian greats who hailed from the city, including Miles Franklin and Mary Gilmore.

She recounted the struggles and peaks of all art disciplines in an address that should have silenced the critics and certainly celebrated Goulburn’s rich history of artistic endeavour.