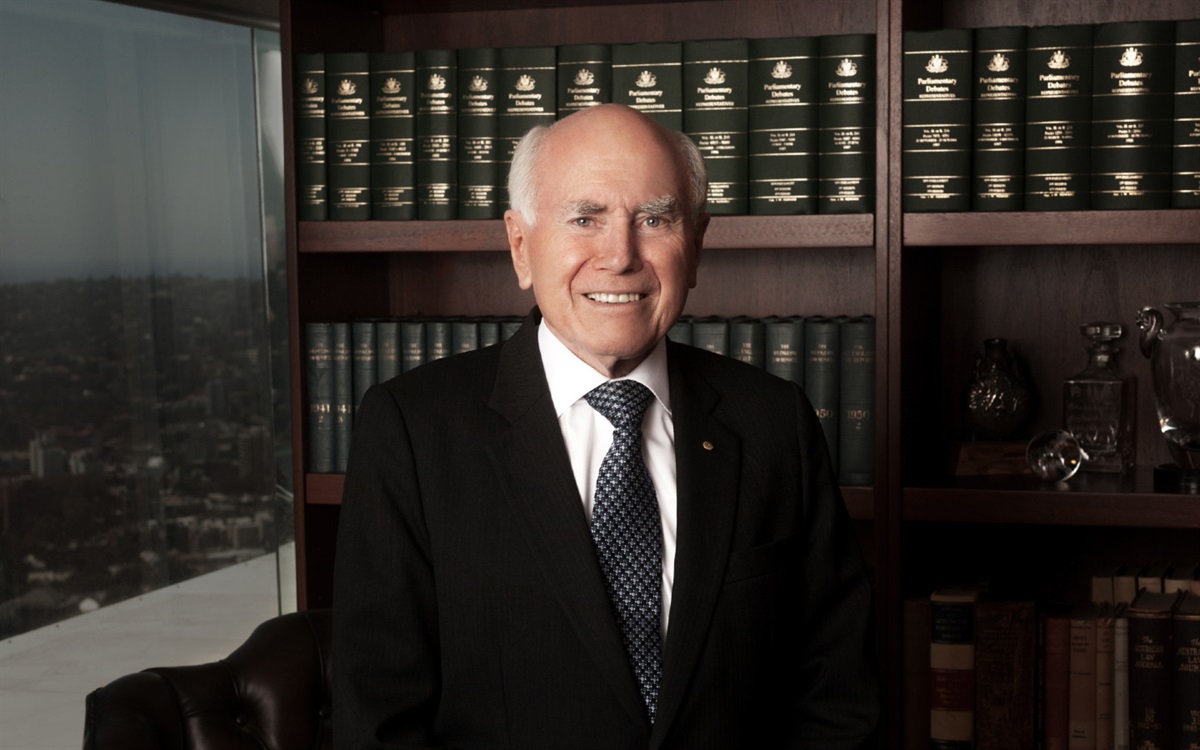

Former PM John Howard was happy for house prices to rise. Photo: Lake Mac Libraries.

Revelations that the Howard-Costello government rejected a 2004 recommendation from that bastion of left-wing thinking, the Productivity Commission, for a review of property tax treatments due to concerns about a surge in house prices shows just how derelict it and successive governments have been on arguably the most significant factor in national living standards.

Last week’s analysis of the housing market downturn from CoreLogic said the obvious – the gap between incomes and prices has expanded to the extent that many potential buyers, particularly first timers, have either given up or are waiting until things become more affordable.

This affordability crunch has been attributed to the steep rise in interest rates but the days of cheap money before and during the pandemic were never going to last and are unlikely to return soon.

Even then, prices were still high and the COVID boom was but the latest in a series of surges that started around the turn of the century and not uncoincidentally after the Howard Government decision to halve the rate of capital gains tax.

Its combination with negative gearing put a fire under the property market, enough for the Productivity Commission in a 2004 report on first home ownership to raise red flags about the tax treatment of property.

It recommended that the government should review “those aspects of the personal income tax regime that may have recently contributed to excessive investment in rental housing”, with a focus on the capital gains tax provisions.

But it also added negative gearing to the list “for addressing distortions in incentives to invest in housing and other asset markets”.

But Cabinet papers released at new year reveal that the government rejected such a review, arguing there wasn’t a clear link between negative gearing and CGT and a spike in prices. Instead it focused on increasing housing supply and handballing the issue of stamp duty to the states.

Sound familar. While Australia’s generous tax treatment of property is but one factor among many contributing to the current state of the housing market, the signs were there two decades ago that this had opened the door to investors who, with greater access to finance, were bidding up the price of property and leaving potential owner-occupiers in their wake.

Along the way, it created a new investor class and fertile constituency for the Coalition, especially when anyone protested that housing for both owners and renters was becoming too expensive and devouring incomes, and negative gearing and CGT were to blame.

The wicked dilemma was that for those who had managed to get into the market, ever rising prices meant they too were invested in keeping the status quo. As John Howard quipped during one election campaign, no one complained about the value of their home going up.

We’re all worried about losing money and for those with massive mortgages the thought of ‘going negative’ if prices fall is terrifying.

Australians have been a on a runaway property train that they can’t afford to get off.

Muddying the water has been the strategy of highlighting so-called aspirational mum and dad investors who might have one rental property, when those benefitting the most from the tax arrangements have multiple properties and are among the nation’s wealthiest.

The galloping prices, surging rents and reallocation of homes to the rental market has fed a self-perpetuating need for rental homes to the extent that a key argument against touching negative gearing and CGT is that rents will go up to due to a resultant shortage of properties, although demand would probably fall as some renters became owner-occupiers.

More recently, immigration has been blamed for all manner of social ills, including the housing crisis. But the stage had already been set and both parties supported the immigration intake, until Peter Dutton’s populist adoption of anti-migrant rhetoric.

The Cabinet papers release vindicates Bill Shorten’s courageous but doomed 2016 election policy to alter the tax settings, because without structural change they will continue to distort the market, in effect giving it an artificial floor.

A quarter century of these settings have created great wealth for some but baked in inequity and adverse social consequences – such as the low birth rate and delays in family formation – that will take a long time to unstick.

The market isn’t about to crash yet but for many – without the bank of mum and dad, inheritances or multi-income households – even lower interest rates, whatever drop in prices might happen and an easing of borrowing rules will not be enough.

The broken nexus between incomes, savings times and prices needs to be restored.

The jig should now be up but a gun-shy Labor is not about to resurrect its policy but focus on building our way out of the crisis, the Coalition will spruik tapping super for a home deposit and the property sector will continue to oppose any change, as it always has.

What should be clear now though is that when Peter Dutton talks about governing in the image of John Howard and Peter Costello, Australians should consider the decisions these two Liberal scions made and how we are paying dearly for them now.