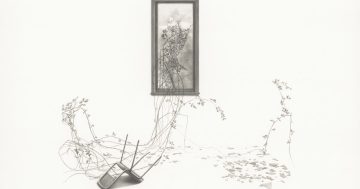

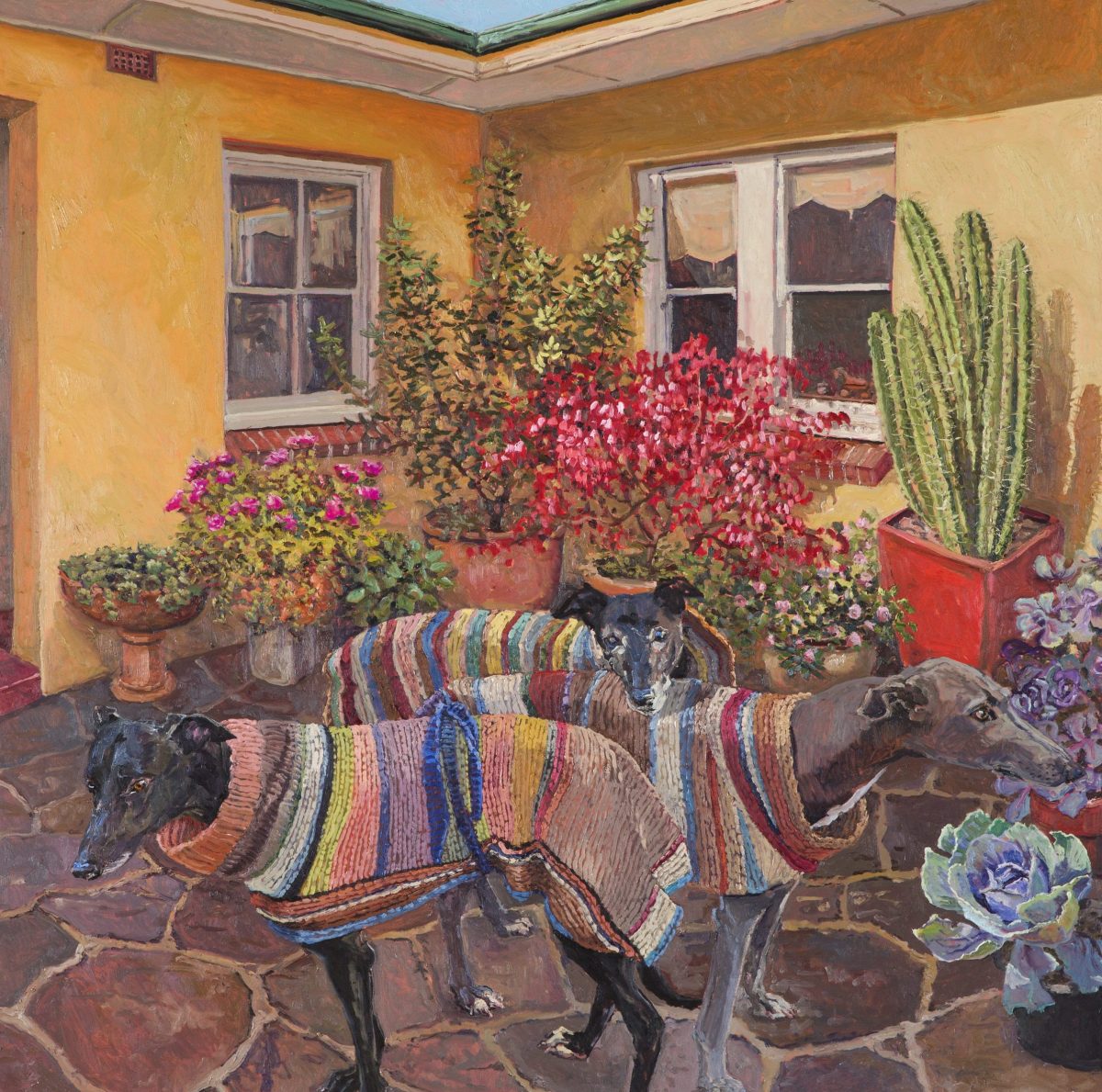

Lucy Culliton’s Crowd scene at the back door is taken from her home at Bibbenluke. Image: Supplied

Lucy Culliton and Graeme Drendel are two of Australia’s most admired and celebrated figurative artists and, for the first time, they are holding a joint exhibition.

Titled ‘Backdrop’, the two artists, each represented by about 15 paintings, present an intriguing and intimate glimpse into their private worlds.

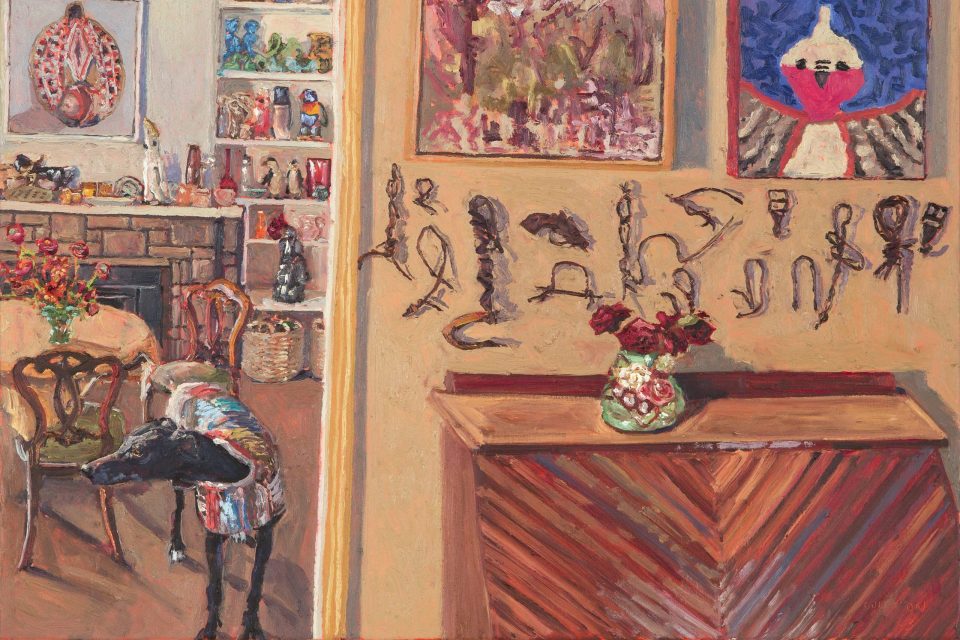

Culliton, who lives in the village of Bibbenluke just outside Bombala, is a colourful chronicler of the everyday. Her painted surfaces are lush and vibrant with an apparent fear of empty space.

Every corner of these beautifully crafted oil paintings is bursting with anecdotal detail. There is a disarming honesty and directness in this celebration of the sense of living in the moment.

Pierre Bonnard once famously said, “Painting has to get back to its original goal, examining the inner lives of human beings,” and Culliton is happy to present her inner life to public scrutiny on canvas. Bonnard did as he preached and painted with a backyard mentality only those things he knew intimately.

In Bonnard’s case, it was frequently sun-lit interiors set in the south of France with Marthe, his mistress and later his wife, shown in various stages of undress.

In Culliton’s case, it is her house and garden on the Monaro, crowded with animals, flowers and domestic objects that are of personal significance to the artist. She is not a hoarder but has difficulty in throwing things out that have a family significance.

Why do people love Culliton’s paintings like The dog room and Crowded scene at the back door? In part, it is because of their sense of authenticity – we believe in the reality being presented on canvas. It is direct, unadorned and a seemingly endless celebration of a reality known to many of us. It is not that the dogs are anthropomorphised, but they are presented as sentient beings that any dog owner knows, as a matter of fact.

The other reason why so many people are drawn to Culliton’s paintings is that they are so beautifully crafted, the colour reflexes are carefully calculated so that the surfaces shine with an inner luminosity. In the popular imagination, parallels spring to mind with Margaret Olley, another lover of Bonnard’s art.

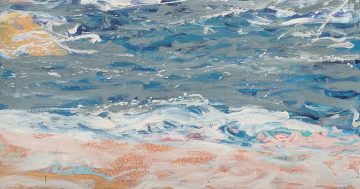

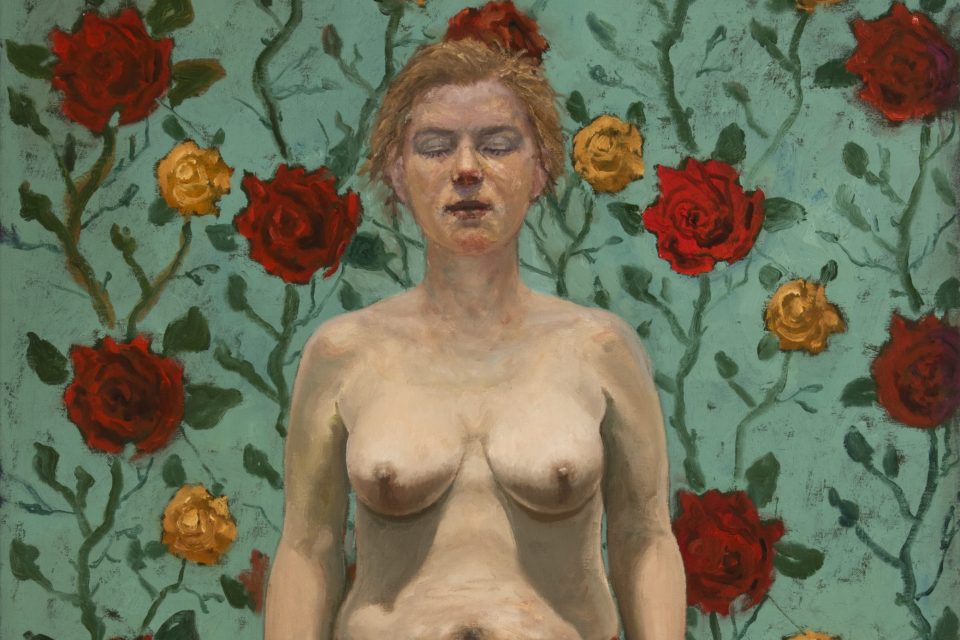

Drendel is a very different sort of artist, one who comes from endless sweeping plains and huge skies of the Mallee in the north-westerly part of Victoria that have become part of his DNA, yet he lives in the inner Melbourne suburb of Coburg. He is also a ‘bookish’ sort of artist who is in love with the Italian Renaissance and ideas of surrealism. Like Culliton, he is primarily an oil painter and a printmaker with an impressive technical skillset that has been developed over a number of decades.

Sometimes I think of his work as a meeting between Piero della Francesca and Giorgio de Chirico somewhere in the outback Mallee.

Like the great Renaissance master Piero, Drendel drains his figures of all emotion – they are impersonal, static and monumental, and like the Italian surrealist master de Chirico, they inhabit a world that seems out of joint as they stand with their eyes closed, contemplating eternity.

In The rose room and The mediator, the model is invited to feel her way through an environment that is strange and unsettling. Is it a nightmare or a waking dream?

The painting that most captured my imagination was The silence, a relatively small canvas where an upholstered armchair that belonged to his late grandmother has been placed into a deserted, featureless Mallee wheatfield under the haze of a blue summer sky. When all extraneous references have been deleted, the viewer contemplates this deserted space in silence and to occupy this chair in their imagination.

Drendel’s star is in the ascendency. Last year he was awarded the $150,000 Doug Moran National Portrait Prize, and he is being sought out by many public art collections.

If Culliton in her art breathes warmth and ‘joie de vivre’ and forms swarm on her canvases in gay abandon, Drendel is an artist of extreme restraint and understatement, so that it is the viewer who feels inspired to invent a narrative for his paintings.

Culliton and Drendel, two very different artistic personalities, do surprisingly combine in the harmonious exhibition ‘Backdrop’ that celebrates the art of figurative painting in oils.

Lucy Culliton and Graeme Drendel, ‘Backdrop; paintings’, is at Beaver Galleries until 23 September, Tuesday to Saturday, from 10 am to 5 pm.

Sasha Grishin is a critic, art historian and writer, currently completing a history of contemporary Australian art.