Does a pre-schooler need to be anywhere near a keyboard or a screen? Photo: File.

As ACT families prepared to head back to school last week, education reporters were busy working up clicks about how the modern child could not get by without technology.

Without tablets, laptops, mobiles, USBs and the internet, the argument went, a child’s future is compromised. And while there was plenty of focus on how much these devices might cost and the impact of a growing digital divide, all forgotten were the well-documented and still emerging downsides of too much screen time, particularly for the very young.

Let’s be clear, computers and the internet have transformed the way we communicate and obtain information but they should not be an end in themselves. There is no question about their role in learning but there remain plenty of questions about the appropriate age for children to be exposed to technology.

There are the obvious physiological issues of being hunched over a device, such as the aching neck, back and shoulders, sore eyes and headaches, or, like television, the way inactivity can lead to obesity and children alienated from the natural world.

Then there is the insomnia brought on by the exposure to a screen’s blue light upsetting circadian rhythms.

Or the dark side of all that connectedness is the cesspit of social media that can lead to distorted values and bullying.

All that is bad enough and we’re not out of primary school yet.

The most insidious aspect of the fast-tech approach is its inherently addictive nature and subtle changes to the young developing brain.

There is a reason some Silicon Valley geeks apparently send their kids to low-tech schools – they know just how addictive the software they’re creating is.

With every click and rush of dopamine, the young brain hungers for more, and as Marshall McLuhan said of TV, the medium becomes the message, a triumph of process over content.

Down every rabbit hole they will go, and many a parent can attest to the lost hours their child has clocked up while ostensibly doing their homework.

It’s not so much a case of the young mastering their computers as their computer’s relentless logic training them, laying down rigid train tracks of mechanical behaviour that is the antithesis of what makes us human – creativity and the imagination.

Separate studies of children using screens for long periods on a daily basis are focusing on the white matter in their brains that support language and literacy skills. They are finding a lower structural integrity between the connections in that white matter – and lower cognitive function.

More research is needed but the signs are not good. Short attention spans, shallow reading and low retention of information are common among heavy screen users.

Unfortunately nobody can say how much screen time is too much but perhaps one should err on the side of caution?

Australia has a history of high and rapid penetration when it comes to technology, which has all the hallmarks of a mass social movement.

Many parents have simply given up on regulating screen time, arguing that it is a part of modern life, all their friends are doing it and the sooner they start the better, egged on by politicians, tech companies and business enthusing about the jobs of the future.

It would be good for well-meaning parents to remember that there is a strong commercial imperative for big tech to flog its wares to as broad a segment of the education market as possible, starting as early in a kid’s life as possible.

They’ve certainly sold it to the education authorities whose obsession with technology sees tablets and trials of language learning devices in child care, the dazzle of electronic whiteboards in the classroom, primary school Powerpoint presentations, and the setting of inappropriate research assignments impossible to complete without access to the internet.

Parents and educators need to ask themselves whether a pre-schooler needs to be anywhere near a keyboard or a screen, or if a lower primary school child should eschew the flowing motion of hand writing, so steeped in our history and an important learning path, for the mechanical tap of the keys.

Does a 10-year-old need to learn Powerpoint? I well remember my daughter spending more time coming to grips with the program and compiling the presentation than actually mastering the simple content she was delivering.

School projects are the bane of most parents and in the ACT there is a deliberate emphasis on self-directed inquiry from an early age. When combined with the infinite scope of the internet, we can see students set topics inappropriate for their age and have them scurrying to Google where they end up down that rabbit hole again.

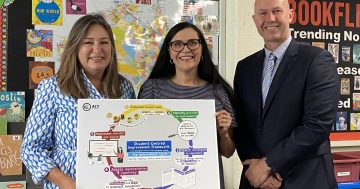

ACT Education Minister Yvette Berry discusses the rollout of laptop devices with a high school student. The ACT Government program aims to bridge the digital divide among high school students. Photo: Supplied.

More often than not it’s the parent who steps in, curates the content and breaks it down into digestible chunks so their child can produce some words to go with the lovely pictures and graphics.

This combination of skim reading, cutting and pasting, and information overload results in the very opposite of what educators are aiming for – deep learning where knowledge is embedded.

My sons had the benefit of an education that respected the developmental stages of the child and where they did not touch a keyboard until high school, but by then they had been exposed to a rich curriculum and developed strong research and writing skills.

Both had little trouble navigating the digital world.

For all the talk about preparation for the jobs of the future, our children need to keep their imaginations and creative powers intact so they can negotiate and adapt to a rapidly changing world. What are those jobs of the future anyway?

What will make a difference, as ever, are teachers who know their stuff and connect with their students on a human level.

So the Education Directorate is right to stress professional development, but can we also have a little more discernment when to comes to the introduction of technology in the kindergarten and classroom and wind back the electronic stimulation so the young child can appreciate the beauty of the natural world around them.

Do you think the world has changed and children need access to technology or is there too much too young?