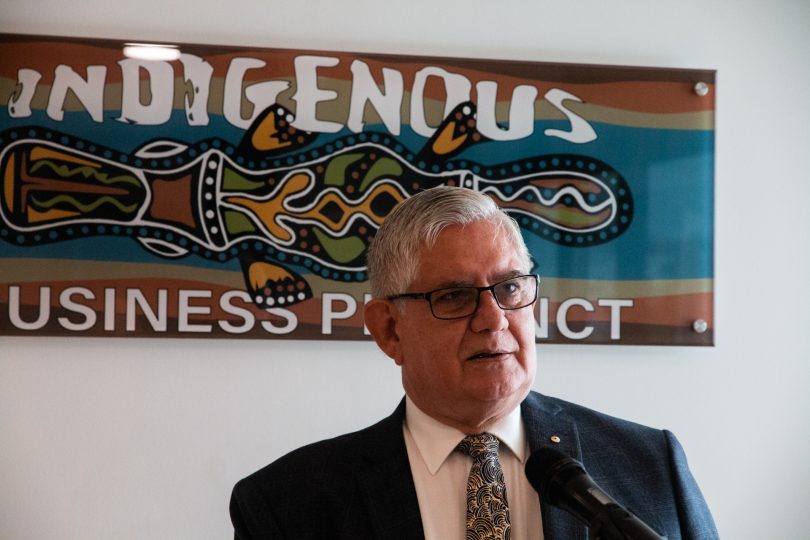

Former Liberal minister Ken Wyatt has resigned from the Liberal party over its decision to enforce a No vote on party lines. Photo: File.

In 1992, the High Court handed down the Mabo decision, laying the groundwork for native title claims later reinforced by the Wik decision in 1996.

It caused near hysteria in many regional communities.

I recall a meeting at the Young Golf Club where speaker after speaker said farms would be taken, long-standing land rights challenged and the economic basis of our existence fundamentally undermined.

All of us were on freehold land that had been that way for a century and a half. It was a legal impossibility that native title, co-existing on pastoral leases, could extinguish those rights.

But the political argument was, nevertheless, couched in highly emotive terms that bore no resemblance to the court’s decision or what actually happened in the intervening quarter century.

Regrettably, the Voice referendum conversation appears to be heading in the same direction as the Liberal Party enforces a No vote without the conscience option, framing the issue as a “Canberra Voice”.

Former Liberal Health and Indigenous Affairs minister Ken Wyatt – the first Aboriginal person to hold the portfolio – resigned from the party on Thursday (6 April), expressing his profound disappointment after working closely with other senior Indigenous leaders across party lines.

Peter Dutton’s position will also cause significant discomfort to moderates in the party leadership like Simon Birmingham and others, including Bridget Archer, who will likely cross the floor on the issue.

Most worryingly, the Liberals’ decision changes the Voice debate from a bipartisan conversation about our national future to a fractured, politicised, point-scoring argument.

Cape York Indigenous leader Noel Pearson views the decision as “a Judas betrayal”, noting that the Liberals had 11 years in power to work on a proposal for Indigenous recognition.

It is worth repeating what the Voice will be – and will not be – in plain language.

It will advise the government of the day on matters closely pertaining to Aboriginal people. That’s all.

The Voice cannot make laws. It cannot mandate expenditure. All it can do is offer advice. All the government must do is listen. The government has no obligation to act.

The Voice provides transparency on who is advising the government on Aboriginal matters. It assures Aboriginal people that other Aboriginal people have given that advice, not mysterious “stakeholders” with other interests.

As Ken Wyatt points out, every other advisory body of this kind set up by Parliament has been disbanded when it suited governments to do so. The Voice would be in the constitution rather than legislated, so government can’t get rid of it.

There has been plenty of discussion about the referendum’s lack of detail.

Former High Court judge Kenneth Hayne notes that the constitution provides a framework for how we run the country, not extensive details about how to do it. That’s for governments, elected by voters, to decide (a side note – NT and ACT residents’ referendum votes have only been counted since 1977).

The referendum change would enshrine the principle that the statistically most vulnerable people in Australia, the first people of the nation, have a guaranteed way to talk to government about issues overwhelmingly affecting them.

The notion that the Voice would proffer ideas on foreign policy and the like is nonsense.

Aboriginal people are catastrophically worse off than almost all other Australians as a demographic. In the 13th biggest global economy, Aboriginal health, education and social outcomes are often at Third World levels.

The Voice would have enough to contend with trying to help government fix issues like extreme poverty, infant mortality and diseases that have been eradicated in every other developed country. Why on earth would the Voice prioritise discussing nuclear submarine purchases or manufacturing industry policy?

There’s also been plenty of media attention on internal Aboriginal opposition to the Voice. This is not unexpected – all communities will differ in their opinions. But polling shows around 80 per cent of Aboriginal people have “very strong” support for the Voice.

The Liberal Party risks demeaning itself by the decision to mandate a No vote or force moderates to cross the floor. The Voice should not be a political discussion, but a national discussion.

Peter Dutton says he will bring the nation together. In reality, he is likely to tear his own party apart.