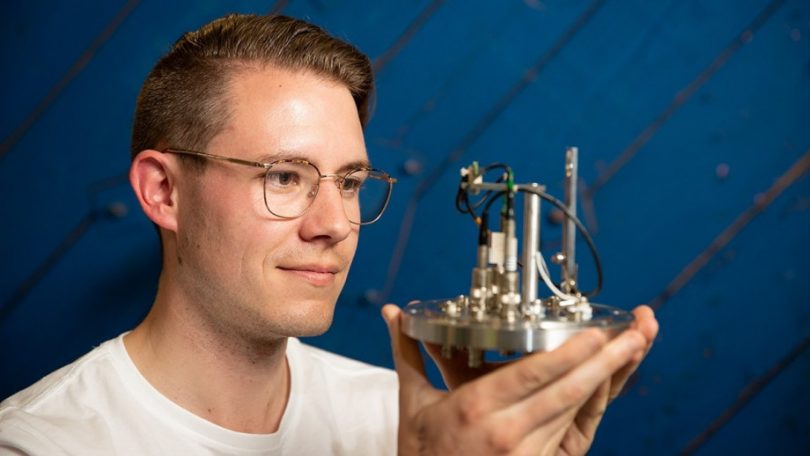

Lachlan McKie is studying nuclear physics at ANU. Photo: Martin Conway.

On the back of a historic deal between Australia, the UK and the US for a new fleet of nuclear-powered submarines, the Australian National University (ANU) says it is ready to train the next generation of nuclear scientists and technicians to fill a gap in our workforce.

For more than 70 years, Canberra has been home to the only university in Australia providing comprehensive training in nuclear physics from the undergraduate to postdoctoral level.

The ANU also runs the country’s highest-energy heavy-ion accelerator – the only facility in Australia which enables hands-on nuclear training.

Head of the ANU Department of Nuclear Physics, Professor Andrew Stuchbery, said the new security deal provides an exciting opportunity for nuclear science in Australia, which until now only consisted of a handful of jobs.

“This deal changes everything when it comes to nuclear science in Australia,” he said. “It ushers in a new era for the nation.

“In the past, Australia’s nuclear technology workforce needs have been minimal and a lot of talented and trained people from across nuclear science have headed overseas.”

The training covers all aspects of nuclear science, including reactor science, nuclear fuel cycles and how to ensure policy debates on nuclear issues are informed by science and best practice rather than myth and hyperbole.

A US nuclear-powered submarine transits through the Arabian Gulf. Photo: US Navy.

Although the plan is for the eight submarines to be constructed in South Australia, it is understood the nuclear innards will be taken care of by the US and UK – both countries with established nuclear industries.

Senior public policy adviser at the National Security College, Dr William Stoltz, said the notion of nuclear-powered submarines for Australia is not sustainable unless Australia adopts domestic nuclear energy production to its agenda.

“In a time of high-end conflict, for example, we will need to be able to service and refuel our own submarines and not solely rely on doing so in the US or UK,” he said. “This makes the path to domestic nuclear energy production a near certainty.”

Professor Kenneth Baldwin – who heads up a research project called ‘ANU Grand Challenge: Zero-Carbon Energy for the Asia-Pacific’ – said the lack of a nuclear industry in Australia is more likely to prompt stronger strategic ties with allies rather than nuclear self-sufficiency.

He said Australia is one of only a few countries in the world that has forbidden the use of nuclear power by legislation.

“Other countries make a decision based on economics and environmental issues and other parameters, but we’ve short-circuited that conversation,” said Professor Baldwin. “Only if this federal law is rescinded can a true domestic nuclear industry move forward.”

Professor Mahananda Dasgupta is the director of the ANU Heavy Ion Accelerator Facility (HIAF), the only one like it in Australia. Photo: Michael Hood.

These days, disasters such as Chernobyl and Fukushima Daiichi are not the issues.

“Safe nuclear power is all about good governance and good management, and both of these were accidents that showed up poor governance and poor management,” said Professor Baldwin.

“In terms of the economics of nuclear power, it’s very expensive, and that’s in part due to the significant costs associated with regulation.”

Professor Baldwin said many other countries don’t have the renewable resources Australia has so choose to go down the nuclear path in their pursuit of zero-carbon energy. For now in Australia, nuclear energy simply costs more than solar and wind alternatives.

The ACT supports 100 per cent renewable energy, but only around five per cent of this is mustered from within its borders. The rest comes from solar and wind farms located elsewhere, which are funded by the ACT Government.

“As you approach 100 per cent renewable electricity, it gets harder to guarantee it will be there when you need it,” said Professor Baldwin. “That means investigating in significant amounts of backup power storage, which can also get expensive.”

But even when Australia as a whole approaches the 100 per cent mark for renewable power, it’s unclear if nuclear will stack up then, either.

Professor Baldwin suspects that point to be only about 10 years away, and by then the costs may well have been driven down enough to make the battery a clear winner.

Even as an tradeable commodity, he said it is far more profitable for Australia to continue as the world’s leading exporter of uranium rather than put it to use ourselves.

Perhaps Australian nuclear power might be dead in the water.