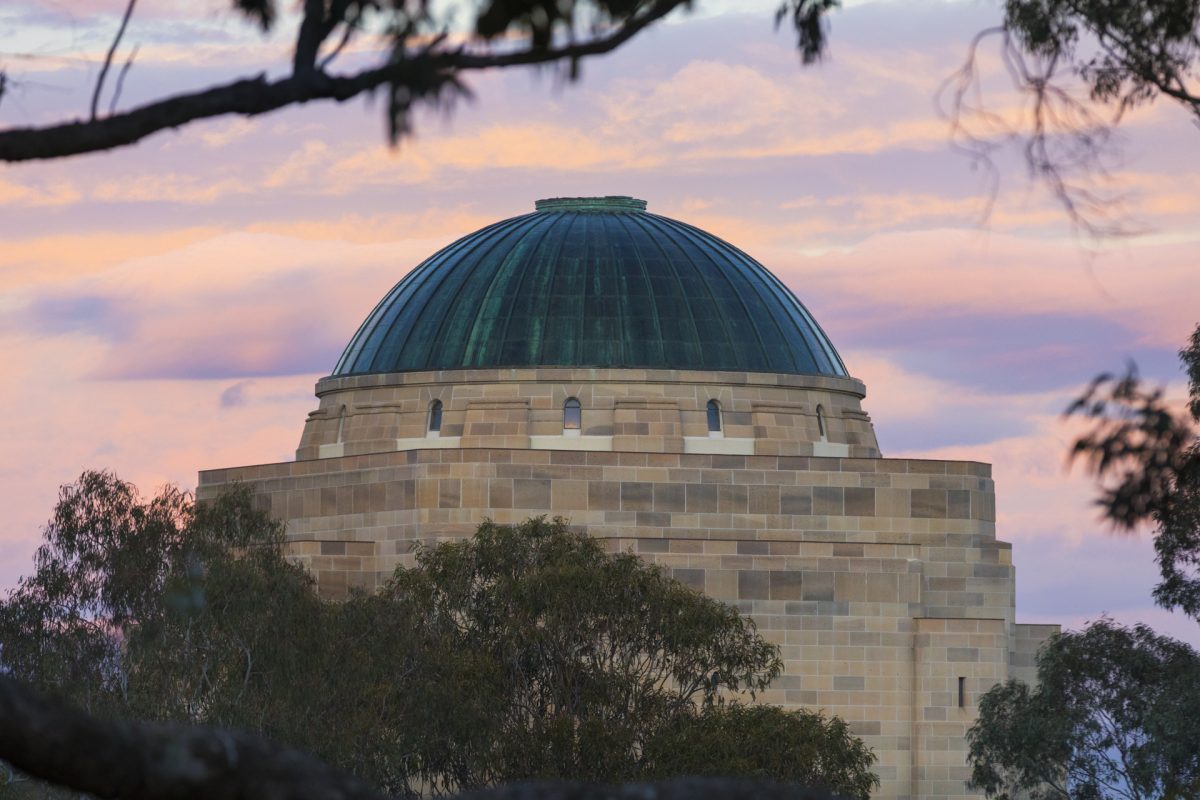

The dome at the top of the Australian War Memorial. Photo: Michelle Kroll.

It’s on all the fridge magnets and postcards as a landmark of the Canberra skyline – the green dome that looms over Anzac Parade from the top of the Australian War Memorial.

But until now, the public has never seen what’s underneath it. Nor known it was actually meant to be clad in terracotta. Or that the green colour isn’t the result of natural weathering, but chemicals added later.

Footage released provides a glimpse into this hidden part of the War Memorial, although staff shy away from describing it as “never-before-seen”. (It’s possible someone poked a video camera up there at some point in the 1950s, but no one has ever been able to track down the results.)

“The opportunity to come up the top is something that not many people get to see,” facilities manager Jana Johnson says.

The Byzantine-esque dome forms the roof of the elaborate Hall of Memory, which holds the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. It was constructed under the direction of Emil Sodersteen, after he joined another Sydney architect, John Crust, in designing the War Memorial.

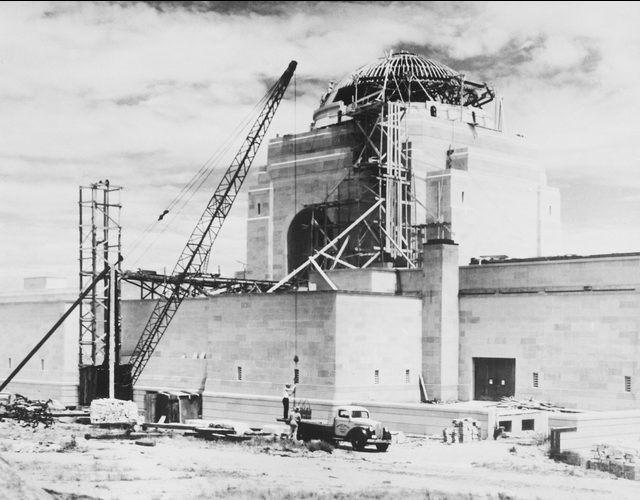

Both had entered a 1932 design competition, but of the 69 entries, Crust’s was the only one to come under budget. The judges were so blown away by Sodersteen’s ‘Art Deco’ vision, however, they put both of them on the job.

Sodersteen took charge of the dome while Crust designed the rest of the building, including the arched cloisters to house the Roll of Honour. Sodersteen later resigned from the project in 1938, leaving Crust to oversee construction by local company Simmie & Co (also behind the National Film and Sound Archive and St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church). This was completed in November 1941.

Most visitors since then will be familiar with the incredibly pretty underside of the dome, where a mosaic – stretching 24 metres above the tomb and made up of more than six million tiles – paints a picture of the “immortality of those who believed in freedom and ultimately died to defend it”.

This artwork was designed by World War I veteran Napier Walter who, despite losing his right arm in battle, helped painstakingly piece it together.

“Within the mosaic, at the very top, you can see a tiny light,” Jana explains.

“There’s an aperture at the top of the dome no bigger than the palm of my hand … which lets natural light through to perfectly frame the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.”

Construction on the Australian War Memorial. Photo: Australian War Memorial.

To get inside the dome, maintenance workers and managers like Jana take one of two stairways to the east and west of the War Memorial’s Hall of Valour. Nine flights (and a couple of wooden ladders) open into a circular cavity girded with steel and Oregon timber beams. Small concrete-silled windows allow some natural light in, and trusses support the copper tiles overhead.

“Sodersteen originally envisioned the dome would be clad in terracotta tiles, but years later, it was thought it would be cheaper to clad it in copper,” Jana says.

The intent was always that the copper would naturally oxidise and turn green, just like the Statue of Liberty. But within a few years, it became clear the air in Canberra is not quite the same as in New York.

“We don’t have enough pollution for the dome to naturally oxidise, so in the early 1950s, chemicals had to be applied to turn the dome the beautiful green colour that you see now.”

Since then, Jana says there have been minor upgrades, mostly to lighting and windows, to bring the dome up to modern safety specifications.

“Whenever we do any works, we’re very conscious of not causing irreversible damage to it,” she says.

And despite all the development work going on at the War Memorial at the moment, she says the dome will always remain.

“Part of my role is behind the scenes and making sure that everything is presented perfectly so that visitors, when they come here, only see the buildings for what they are so the symbolism shines through,” she says.

“The Hall of Memory is not being impacted by the development works … and we do everything we can to protect the heritage building.”