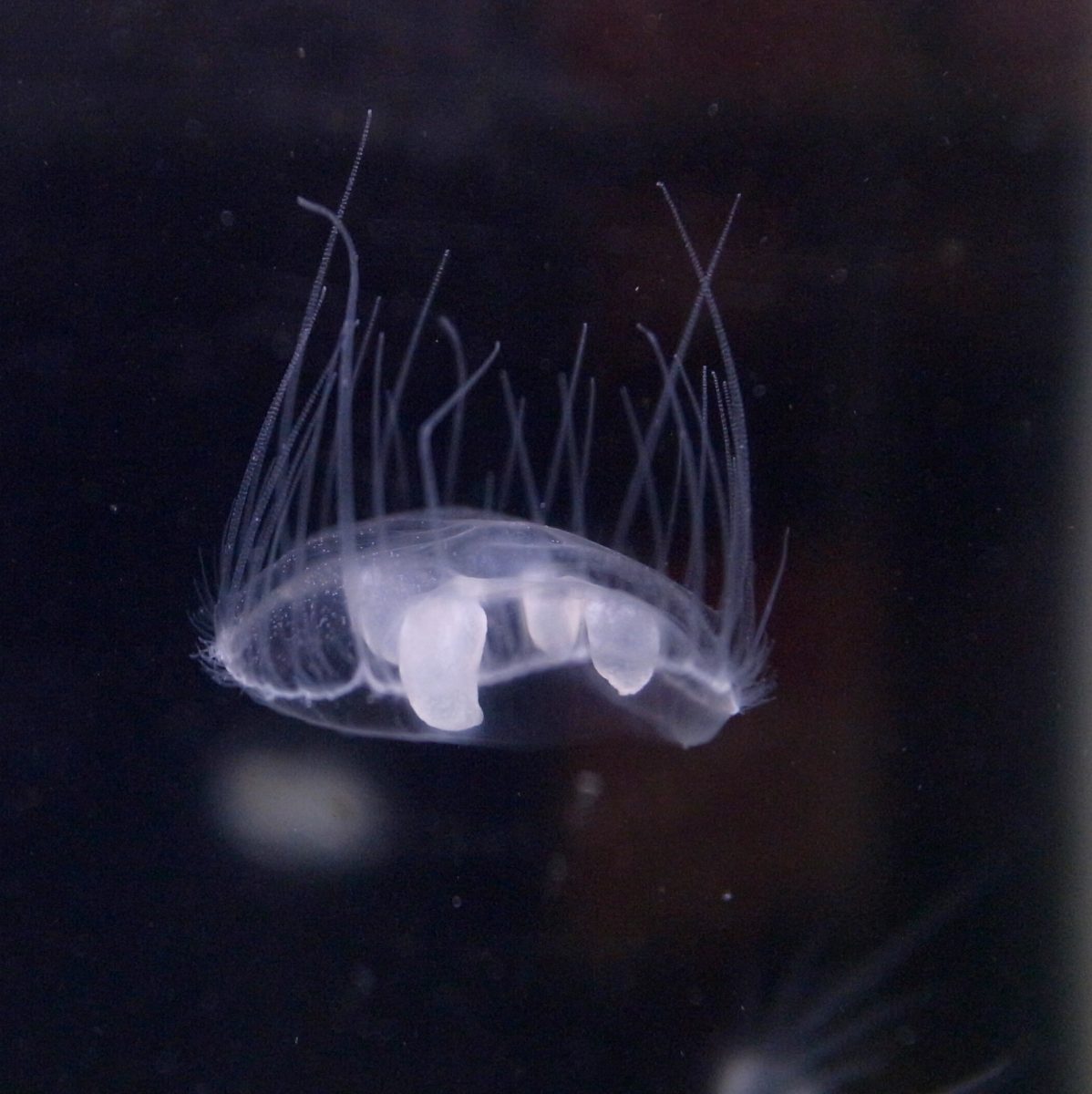

Millions of Craspedacusta sowerbii have made their home in Lake Burley Griffin. Photo: Open Cage, Wikimedia Commons.

One Saturday afternoon in 1967, a Campbell resident was sailing on Lake Burley Griffin when he scooped a white, glass-like blob out of the water with a paper cup.

“I looked over the side and there they were, thousands of them – I would say one for every foot,” Mr GP Robinson later told The Canberra Times.

“I have been sailing on the lake frequently, but this was the first time I saw them come up. It’s quite interesting because I have never seen jellyfish in freshwater before.”

The thought of jellyfish thriving in Lake Burley Griffin might sound outlandish, but they were among the first animals in the lake when it was filled in 1964. Now in 2022, chances are there are greater numbers of them than ever before, thanks to the huge amount of rain.

But how did they get there? And should we ask those enlisting for the next Lifeline Nude Charity Swim to bring along a bottle of vinegar?

Eldon Ball did his PhD thesis on jellyfish polyps at the University of California, before joining the Department of Neurobiology at the Australian National University (ANU) as a Research Fellow in 1971, specialising in arthropods and marine invertebrates.

He says the jellyfish in Lake Burley Griffin are the freshwater species Craspedacusta sowerbii. In fully grown ‘medusae’ form, these jellyfish can measure up to 25 mm in diameter with 400 tentacles tightly packed around the ‘bell’.

“They only appeared in Australia in the 1950s but have spread all over ever since,” he says.

“They’re believed to have originally come from the Yangtze basin in China.”

Lake Burley Griffin has an average depth of four metres. Photo: James Coleman.

The ACT was the first place they were discovered in eastern Australia in 1961. But nobody knew where they came from.

Once the lake was full three years later, they were reported to appear at an average of once a year for several weeks before disappearing again. These ‘blooms’ were put down to a combination of the right climate and the right minerals in the water.

“I don’t know exactly how abundant they are, but I’ve read of times when there is almost a carpet of them,” Dr Ball says.

There are two working theories.

“One is that they come on bird legs during a resting stage of the jellyfish’s life cycle. But the most likely one is when people import shipments of aquatic plants, the polyp stage of the jellyfish comes with the plant, and get into the waterways from there.”

The latter also explains the sudden appearance after World War II, thought to be due to the transport of military equipment.

As resting polyps, the jellyfish can survive temperatures as low as 4 degrees Celsius. Once the water warms to between 15 and 33 degrees, they move into the reproductive medusae phase and more jellyfish result. However, it isn’t always that simple.

“They come and go in surprising places at surprising times, and nobody’s quite sure if there’s a direct link,” Dr Ball says.

“Jellyfish feed mainly on little crustaceans and mosquito larvae, so if there’s a lot of phosphate and nitrogen washed into the lake – as has been the case in these last few weeks – it could give rise to phytoplankton. The crustaceans feed on the phytoplankton, and then, in turn, the jellyfish feed on the crustaceans.”

Including polyps, Dr Ball estimates there to be “millions” of freshwater jellyfish in Lake Burley Griffin today, mainly by the shore within the top metre of water.

And the good news?

“They don’t sting swimmers but have been reported to injure goldfish fins.”