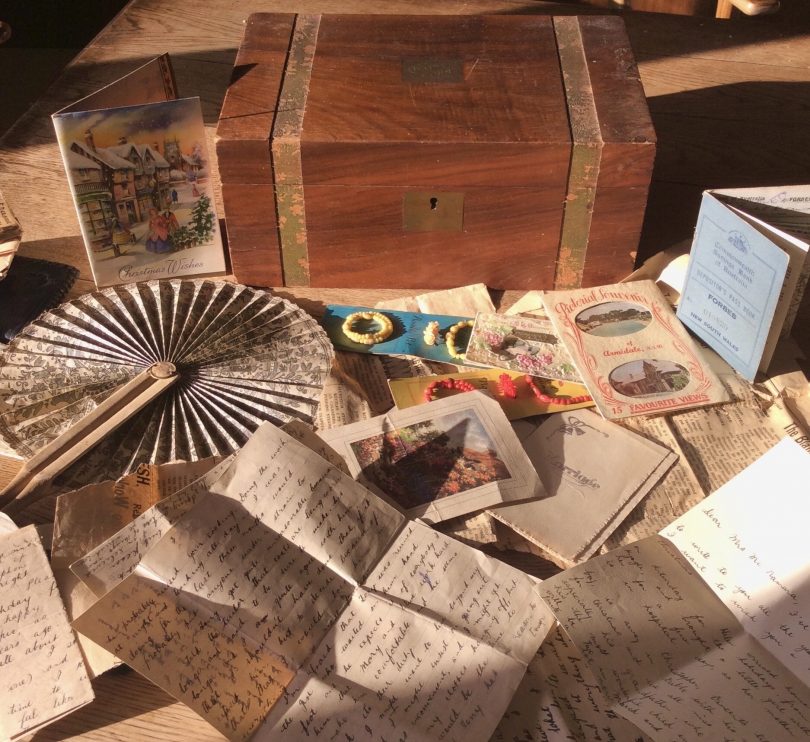

The writing box is a time capsule of mid-century rural life in Australia. Photo: Genevieve Jacobs.

Sitting in the winter sunlight on my kitchen table, a pretty old wooden box is showing its age.

The leather straps that once bound it have long since disappeared, the wood could do with some polish, and the nameplate, with ‘Daisy Conn’ engraved in gentle curlicued flourishes, has dimmed with age.

Daisy was my grandmother, born at the old Stone House near Young in the mid-1890s. She married my grandfather, Gus, bore him eight children and lived a comfortable and uneventful life at Quandialla in a rambling old double-brick homestead.

The box is known as a writing slope, and inside there are compartments for ink, stamps and stationery. It’s filled with creamy, crackling pages of correspondence from the early 1920s to the late 1960s.

They include my grazier grandfather’s rather mundane love letters, describing in detail what the stock and station agent thought of the two-tooth hoggets, and concluding, somewhat unsentimentally, “I will leave off now, darling Daisy, because the flying ants are getting down the back of my neck.”

From Daisy’s middle years, there are letters from her melodramatic friend who was married to the local GP.

“My dearest and only friend, I write, trembling, from my sick bed,” says Lillian, who seems to have found life in the back blocks of western NSW a little tedious.

Other, more poignant letters are from Daisy’s sister, May, dying of tuberculosis and desperately worried about what would happen to her husband and baby son. Daisy sent money, love, and later helped raise young George after his widowed father couldn’t cope and disappeared from his life.

The writing box contains cards, a bank passbook, a fan and many letters. Photo: Genevieve Jacobs.

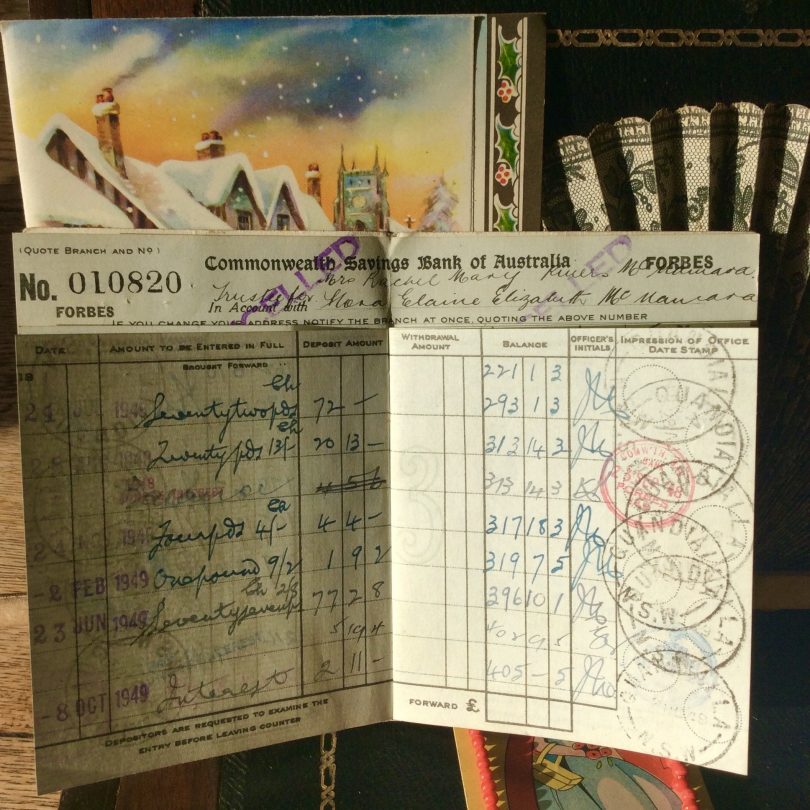

But among the evidence of rural Australian mid-century life – wedding invitations, a ticket to the NSW Lawn Tennis Association championships in 1950, a passbook for the Commonwealth Savings Bank in Forbes – a tale of thwarted love plays out in copperplate.

The dramatis personae are my late Uncle Tony, a tall cheery man who loved a joke, and his former fiancee, Dorothea, who met him after she boarded with my aunts at the convent in Forbes during the war years.

Putting it bluntly, Uncle Tony left Dorrie virtually at the altar with “a white organdie dress which will do very nicely for evening”, a lot of wedding china and a broken heart.

“I don’t want to make this letter too long because it’s a case of the less said the better,” Dorrie begins, before going on for a further five pages.

She writes to my grandmother asking for her saddle and riding gear to be packed up, her letters returned and her love given “to all at ‘Richmond’ of whom I am so fond, dear Mrs McNamara – all but one!”

The engagement seems to have ended after Dorrie told Tony’s tailor that men’s coats were being worn longer that season. This prompted accusations that she was interfering, although Dorrie hastens to point out that, “I was never CRAZY about him – as he professed to be about me!”

Alas for Dorrie, as the contents of the writing box show, by 1948 Uncle Tony was heading down the aisle at “St Canice’s, Elizabeth Bay, and afterwards at the Pickwick Club” with Aunty Gay. She’d been a dashing WAAF during the war and was a lot of fun, a light-footed dancer, and in later life given to cloaks and sweeping hats ornamented with pheasant feathers.

Uncle Tony called her ‘Sparrow’ – she was a solid size 18 by the time I knew her – and always found her vastly amusing, if a bit of a handful. If memory serves correctly, Dorrie married someone else and all was well in the end.

The letters are echoes from another, gentler and slower world. One where you could lose a fiancee by misdirecting his tailor, console yourself with having acquired another evening dress, and remain on very good terms with his mother.

And in this social media addled age where images flash around the globe in nanoseconds, perhaps that is a loss.