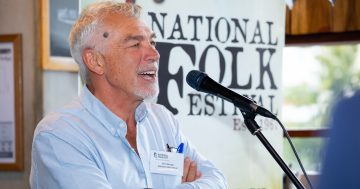

Unwanted after decades of service: ANU School of Music teachers David Pereira and Tor Fromyhr. Photo: Ian Bushnell.

Two of the ANU School of Music’s most distinguished teachers are fighting for their jobs after being shown the exits in an action that has shocked their students and cast a shadow over the future of performance studies at the university.

Violinist and viola player Tor Fromyhr and celebrated cellist David Pereira have decades of teaching experience at the ANU between them, but their 12-month, fixed contracts have not been renewed.

Pereira’s contract expired on 9 February, and Fromyhr’s will end on 20 March. The National Tertiary Education Union is seeking to resolve the matter through the ANU’s internal disputes process, which entered the final stage yesterday (26 February). If there is no agreed outcome within two weeks, the matter will end up in the Fair Work Commission.

They had originally applied to convert their rolling contracts to continuing positions but were told this would not be possible due to a then review of the School of Music.

NTEU ACT secretary Dr Lachlan Clohesy said the pair should never have been placed on a 12-month contract because, under the Enterprise Agreement, there were only limited circumstances under which a university could use them.

“Both Tor and David were appointed incorrectly for what ANU has claimed is a specific task or project which we say is ongoing work,” he said.

“They’ve been doing this for years. They’ve been there for decades. It’s clearly ongoing work.

“The shabby treatment these long-term ANU staff have been subjected to has been shameful.”

The ANU would not say why the pair’s contracts were not renewed, but Dr Clohesy said an email to 70-year-old Pereira raised the question of age discrimination.

“I believe it is, however, now a time to allow a new generation of talented musicians and academics to establish themselves and be well-positioned to lead and shape the ANU School of Music into the future,” the email from Professor Kate Mitchell, director, Research School of Humanities and the Arts, said.

The pair’s work has been handed to casual teachers.

NTEU secretary Lachlan Clohesy: “The shabby treatment these long-term ANU staff have been subjected to has been shameful.” Photo: Twitter.

Dr Clohesy said the new agreement provides a remedy to the incorrect use of fixed-term contracts, and the union had already successfully converted six staff at ANU and one at UC to continuing positions.

Fromyhr, who this year marked 50 years of tertiary teaching, said the situation was bewildering.

He said it had taken years to rebuild trust after the damaging School of Music cuts of 2012, and part of that had been the outreach that he and Pereira had done to attract students.

“It’s been hard work to bring it back to the point where people would trust coming back to study music in Canberra. The last five years have shown that it’s possible.”

Seeking a more secure position was part of cementing that trust with students that their teachers would be there.

“When I started, I had mentors who were very experienced, and I’ve been a mentor to many since then,” Fromyhr said.

A regular Principal Viola with the Canberra Symphony Orchestra, Fromyhr could point to a dozen CSO players who were his students.

“That is mentoring the next generation of young musicians,” Fromyhr said.

He said musicians did not usually retire but kept teaching well into their later years.

Fromyhr, who has Indigenous heritage, has also been involved in the young Indigenous composers program.

He had thought the new agreement could guarantee him a secure position instead of being on rolling contracts.

“Finally, we can get this sorted out, and I can focus on my job, not just doing what I have to do to please somebody in the university to get another year’s contract,” he said

“Focus on my job of continuing to build and bring back a string area within the university that had such a big reputation over decades, that it hasn’t for the last decade and is now just starting to come back.”

Pereira said it appeared the ANU had manoeuvred the pair, the last of the pre-2012 staff, into a position where they could be eased out of the School, and it seemed like a version of casualisation of the workforce at the ANU.

“Being excellent at what you do is of no real importance,” he said.

He believed the email he received about a new generation did not pass the pub test.

In 2012, the ANU School of Music endured a controversial restructuring and ongoing turmoil that damaged its reputation for years. Photo: ANU.

Pereira said he was saddened that there were a handful of excellent young people he couldn’t work with anymore.

He said one actually came to ANU from Malaysia to specifically study under him, which is the way many aspiring musicians, including himself, seek out a mentor.

That student, 23-year-old Eloise Ng, has a year to go in her degree and will continue with her new casual teacher and privately with Pereira at her own expense.

Others, though, will drop their music studies.

Ms Ng said she was very upset and her family was worried about what it meant.

She believed the ANU, which had not told her she would not be continuing with her teacher, was not doing the right thing by its students.

She has not started with her new teacher yet and was unsure how that would go.

Dr Clohesy said the misuse of fixed-term contracts and other forms of insecure employment was at epidemic levels across the higher education sector.

“The only cure is for staff to take concerted, collective action through their union,” he said.

“ANU agreed to this Enterprise Agreement relatively recently. It is disappointing that they are shirking their obligations so soon after 94 per cent of staff approved the agreement.”

An ANU spokesperson said the university did not comment on individual staffing matters.

The spokesperson said this decision would not impact ANU students and their studies.

“ANU students will still continue to receive the best tuition possible for these particular subject areas,” the spokesperson said.

The ANU was committed to giving more staff on fixed-term contracts greater job certainty where those opportunities were available, and a number had already done so under the new agreement.