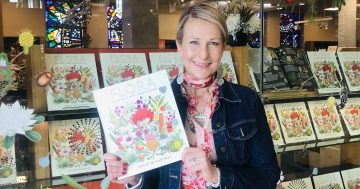

Director-General National Library of Australia, Dr Marie-Louise Ayres. Photos: Michelle Kroll.

Although not born in Canberra, National Library of Australia Director-General Dr Marie-Louise Ayres does not have to look far to be reminded of her deep connection to the national capital and from where some of the attributes that have guided her career spring.

Her engineer father was the project manager for the construction of Telstra Tower. As a teenager and student of female writers, Dr Ayres thought there was little in common but at a pivotal point in her career, she realised she had inherited a logical and structural brain perfectly suited to managing archives and the big digital projects that have been her hallmark.

The recently reappointed Dr Ayres came to Canberra as a child in the public service migrations of the late 1960s and spent all her schooling here before heading off to the University of New England.

Back in Canberra towards the end of her PhD on Australian women poets in 1994, Dr Ayres was reconsidering academia when she was asked to apply for a low-level job at UNSW ADFA library, where her expertise in Australian literature could come in handy.

“Very quickly I realised that this whole world of libraries was one where I could be very happy and work very effectively,” she says.

Dr Ayres spent eight years at UNSW ADFA, including leading the three-year AusLit project bringing together a range of literary databases.

It was there that she and her colleagues sensed the potential digital technology and the nascent internet offered.

“We would sit around and say ‘if I’m a researcher in the future I might want to know who are all the female poets of Chinese Australia heritage who were born in the Mallee area between 1950 and 1970’,” Dr Ayres recalls.

“We would ask ourselves wild questions like that in order to build a database and technology was right at the point where you could ask those wild questions and build something that would let you answer them.

“I’ve never lost that excitement, that sense of building big digital systems that need an awful lot of grunt under the hood to serve an array of queries that you can’t possibly predict.”

Dr Ayres has recently been reappointed for a second term.

It’s now just over 20 years since she went to the National Library to project manage the online Music Australia service. In 2006 she became Manuscripts Curator, also assuming responsibility for the Pictures collection when the two branches merged in 2010.

But it is probably her five years leading the trailblazing Trove digital archive that made her name and has also taken the NLA collection, and 1000 others, into Australian homes and consciousness.

It became so popular that a proposed funding cut provoked a storm of protest, making it politically unpalatable, and virtually guaranteeing its future.

“I think that means that both sides of government can really see Trove’s utility; particularly for Members of Parliament who are representing regional and rural areas, and often feel a bit left out, and they know that’s not the case with what we’re doing,” Dr Ayres says.

Dr Ayres is quick to point out that Trove didn’t come out of nowhere, but from decades of experimentation and a determination to do something new in a digital environment.

The result has turned out to be much bigger than any could have ever imagined.

But asked if Trove is the Library’s greatest triumph, Dr Ayres points immediately to the entire NLA collection of 10 million physical items and terabytes of digital files collected by generations of people over decades.

“If you haven’t got a collection, you can’t do any of the things that we’ve been doing with Trove,” she says.

It is a jewel in the crown though, and securing long-term funding is high on her to-do list over the next five years at the helm.

Funding tensions are a fact of life for Canberra’s National Institutions, and Dr Ayres is philosophical about the NLA’s relationship with government, which has come to the party in recent years but has made it clear that it wants the Library to raise some additional revenue.

“We will be responding to that in different ways, and then make hard decisions,” she says.

That’s something Dr Ayres has not shied away from, such as dramatically scaling back overseas collecting and almost ceasing collecting from Asia, which was criticised as short-sighted but was due to a combination of resourcing restraints and very low usage.

Her 2018 decision to restructure the Library was controversial and caused much heartache but Dr Ayres has no doubts it was necessary.

“We hadn’t had a major structural change for 20 years and there were just frictions and gaps all over the Library,” she says.

While Dr Ayres acknowledges there will be people who will curse her for the rest of her time at the Library, she says her team acted with integrity and the process was transparent and honest wherever it possibly could be.

Despite the focus on digital capacity, much of her time in coming years will be taken up with securing a new storage facility for the 18 kilometres of material sitting with the National Archives that will need a new home by 2025.

There is replacing the hail-damaged roof, installing a new cooling and heating system and then there are windows that need replacing. Her father must loom large when she considers these.

But there will also be fighting for sustainable funding for the Library’s future and its collecting capability.

Dr Ayres says women should step forward in the public service even more than they already do.

Dr Ayres may be realistic about funding but that doesn’t mean she won’t be a fierce advocate for the Library and how it should serve the nation.

She says government and the public don’t really understand how important the Library and such institutions are.

“It’s like electricity and plumbing, you don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone,” Dr Ayres says.

“The general public, even in Canberra, would not have a good understanding of the extent of the pressures faced by cultural institutions.”

The other priority for her is for the Library to better reflect the incredibly diverse country that Australia has become.

“I’ve really challenged everybody in the Library to really commit to recognising that we must serve the full diversity of the Australian population, wherever they live, whatever their language is, whatever their cultural background is,” Dr Ayres says.

Many of the people who walk into the library still look like her – white, 50-something and female – and that has to change.

Of course, the Library has changed for the better, and is now more of a community hub than the institution that was not so welcoming to a young and very pregnant university student many years ago.

“I often reflect on that because I think about how much the library service has been expanded nearly four decades since I had that experience. It’s a radically different place in terms of its audience outreach than it was in its early years,” Dr Ayres says.

It’s been a serendipitous career and it’s a process that Dr Ayres encourages others to embrace, in that opportunities should be grasped whenever they arise even if you feel you’re not ready for that next challenge.

She says that’s particularly the case for women, some of whom may lack the confidence that can come more easily to their male colleagues, suggesting gender remains an issue in the APS.

“So I would say women step forward in the public service even more than you already are,” Dr Ayres says.

She might also say, have no regrets because she certainly has none about leaving academia behind, driving the digital focus or making those tough calls at the Library.