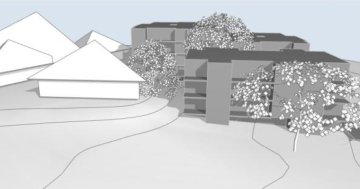

Community Housing Canberra is sourcing land to build affordable homes for low to moderate-income earners to rent or purchase. Photo: CHC.

Job seekers are turning their backs on desperate Canberra businesses because they can’t find rental accommodation, and if they can find somewhere to live, it’s often unaffordable.

Business owners, particularly those in the service and hospitality industries, are crying out for staff and claim the shortage of affordable rental accommodation in the Territory is having a serious knock-on effect on the economy.

A Canberra business owner for more than 40 years, John Runko says businesses are bouncing back after the COVID lockdowns, but they cannot find staff.

“There are not enough people to fill the positions that are currently vacant,” he said.

“We don’t have enough labour to perform all the tasks the city needs – there are more jobs than people available.

“There are so many businesses needing staff that they are obviously trying to attract people from interstate, but when candidates discover the lack of rental accommodation and the cost of it, they’re saying it’s too hard and not worth their while taking up the job.”

Even if the ACT could attract much-needed essential workers in a hurry, where would they live? Photo: File.

Mr Runko says Canberra is one of the country’s most expensive regions to rent and is on par with some of the most exclusive suburbs in Sydney.

He said the ACT was not an attractive option for interstate job-seekers. At the same time, many Canberrans were being forced to move out of the city to more affordable outlying areas, leaving business owners high and dry.

“I’ve been in business and the property industry in Canberra for four decades and this is as bad as I’ve seen the rental market, in terms of both affordability and the tightness of it,” he said.

“There are so many people already being hammered with cost of living and it’s causing so many issues. It’s making life in Canberra very hard for low-income earners, casual or part-time employees and students just trying to make ends meet.

“We’ve found ourselves, as a city, unable to address the needs of our community. This has to change.”

Homeground Real Estate business development manager Maria Edwards says with increased cost of living pressures in other areas, such as food and fuel, family budgets are being stretched more than ever.

Every day she sees people desperate to not just get a roof over their heads but one they can afford to live and thrive under.

“What we are finding is that tenants are becoming more cautious and not overcommitting themselves with rents, which is putting more pressure on the lower end of the scale,” she said.

“For example, someone who may have rented a property for $750 last year is now trying to find properties in the $650 range – which just means there is more competition for medium to lower-priced properties.

“This seems to be resulting in prices for top-end properties coming down a bit, which is positive, but it will take a while for landlords to shift that mindset, especially when interest rates are rising and they are looking at their own financial positions.”

She said increasing interest rates also prompted landlords to pursue maximum rent rises when renewing existing leases.

Renters are lining up to take advantage of Homeground’s Affordable Housing scheme, with a unit in Braddon recently attracting 60 enquiries, the majority of which were from young singles or couples finding it almost impossible to secure a rental for under $500 per week in the city.

With the government looking to increase the number of overseas workers to help bridge the employment gap, Mr Runko says it will place even more pressure on the under-supplied rental market.

“Increasing immigration sounds like a good solution for businesses, but where will these people live when they get here, and how will they afford to live here?” he asked.

Ms Edwards agreed that once skilled migrants start returning to the ACT, there will “definitely be more pressure on the market, especially since typically they don’t start out in the top earning brackets”.

ACT Council of Social Service (ACTCOSS) CEO Dr Emma Campbell says housing insecurity has become a “real concern” for health workers and community employees who are being “pushed into serious financial stress”.

She said essential community sector workers would need to use a substantial portion of a normal week’s wages to rent an apartment in most Canberra suburbs.

“To rent in the inner north or south, an essential community sector worker would need to sacrifice more than two-thirds of a full working week’s income to rent an apartment,” Dr Campbell explained.

“These are the people who have helped us get through the pandemic. Yet, across the ACT, these workers cannot compete for rental properties.”

During the COVID housing boom, many mum-and-dad landlords exited the market and homes were snapped up by live-in owners. As a result, more investors are leaving the market than entering it, which has reduced the rental pool and, in many cases, the demand has driven rents up.

Community Housing Canberra is helping low-income earners by developing properties that are sold under the ACT Government’s Land Rent Scheme. In contrast, others are sold directly to the market as off-the-plan apartments, townhouses and houses.

While organisations are “making an effort”, Mr Runko says it’s just a drop in the ocean. He says Canberra needs between 2000 and 3000 additional rental properties “right now” to accommodate the employees needed to keep the city working.

“We need all stakeholders to put their vested interests aside and come together to ultimately increase the supply and diversity of rental properties in Canberra,” he said.

“One of the more practical solutions is to encourage build-to-rent on a greater scale. If we can get enough people to start building these – by the hundreds – that has to ease supply somewhat. The problem is, that will take three to five years to happen.”

While there is no simple solution, Mr Runko says one big step towards meeting housing demand would be for the Federal Government to free up land and the ACT Government to encourage more large rent-to-buy developments.

“There is no short-term answer, but we need to stop talking about ‘hope’ and start acting right now,” he added.