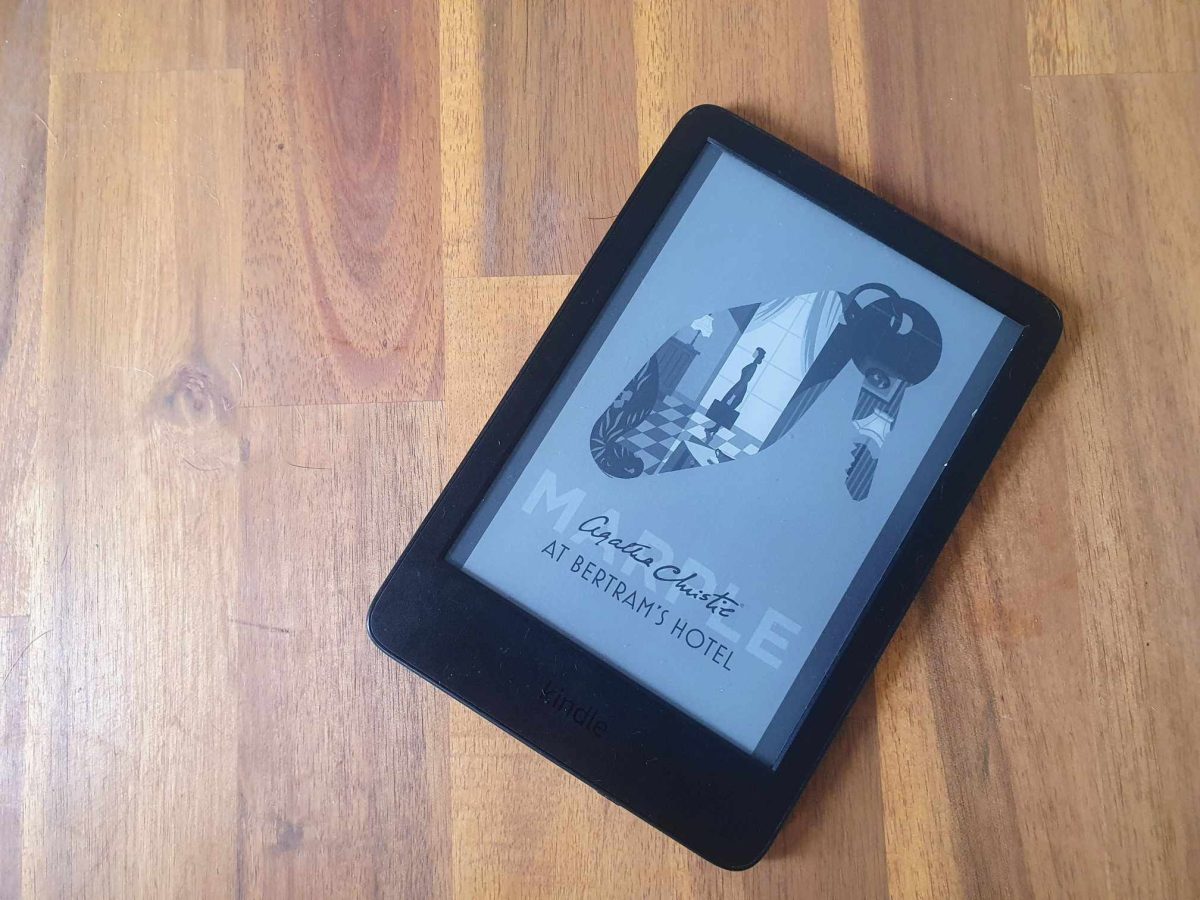

Believe it or not, we’re not the first generation to suffer an egg shortage – just ask Agatha. Photo: Zoe Cartwright.

If headlines about the climate crisis, Trump administration, war in Ukraine and the Middle East and other tragedies open up a pit of despair in your stomach, you’re not alone.

I know some hardened newshounds who have had to take a step back from the constant barrage of death, disaster and callous cruelty. We’ve just started 2025 and instead of being imbued with a sense of optimism, many of us feel defeated.

I’m not a psychologist, therapist, counsellor or reiki healer; but I do have one suggestion that’s worked for me.

Give Agatha Christie a read.

Despite the subject matter – murder, and the adjacent fallibilities of human beings – Christie provides some respite from the uncontrollable chaos of the outside world.

First, if you’re reading any book at all really, you aren’t reading or listening to headlines about the latest executive order in the US and its consequences.

Second, you’re giving your undivided and sustained attention to something – good for the brain.

Also good for the brain is figuring out the puzzle mystery, whodunnit and how.

Thirdly, and for me right now most importantly, you get an idea that people have always been, well, people.

Her first book, The Mysterious Affair At Styles, was published in 1920, and her final novel published during her lifetime was Curtain, in 1975.

A good chunk of her catalogue is set in the time around World War I and World War II, a time marked by political, social and economic instability, the Spanish Flu pandemic, the Great Depression and the rise of fascism.

Despite superficial differences in technology and fashion, the context feels all too relatable.

Characters complain about how hard it is to get eggs, increases in property tax and radical youth – often over a luxe dinner from the refuge of their comfortable homes.

They worry about their family, their friends, their looks, their careers, as well as the unrelenting and at times shadowy political forces that shape their worlds.

It’s easy to feel as though the splintering of perspectives in our community is purely due to the evils of technology, social media and the 24-hour news cycle.

But in 1946 one of her characters, Hercule Poirot, notes that “every single individual had a different version of the theme ‘what did we fight the war for?'”.

There’s something reassuring in the realisation that we are now as we were then – fallible, self-obsessed creatures walking around with plenty of half-baked ideas in our brains, and precious little understanding of what’s going on in the wider world, or even in the internal worlds of those we love best.

That many of us have the ability to shine brilliantly in one particular context – say, on a battlefield – but that those very same attributes can let us down badly in other environments.

Christie isn’t perfect – her writing reflects the attitudes she grew up with, and if 1920’s-era casual racism, homophobia and more is not for you right now, absolutely fair.

But she does do a brilliant job of showing us where ordinary people can have the biggest impact on the world around them.

Being thoughtful, being kind, using our talents and our resources to uplift the community around us might not end wars, but they are all actions within our reach.