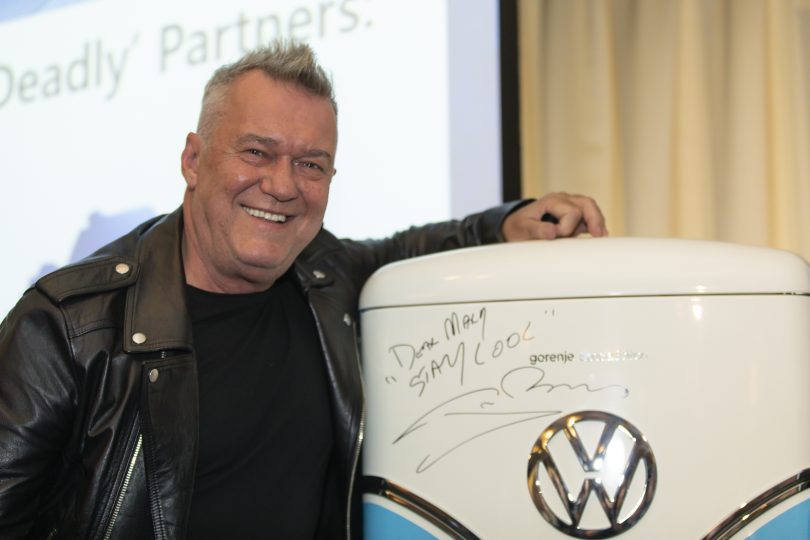

Region Media Group Editor Genevieve Jacobs interviewing rock icon Jimmy Barnes. Photos: Region Media.

When Jimmy Barnes was a kid in Elizabeth, South Australia, his family life was so bad that he would sit on the edge of a pier and dream about swimming out into the distance so the pain would end.

“I was a time bomb ticking,” he told the audience of 500 at this year’s Menslink breakfast. “I was suicidal at eight years old. All I could think was it would be nice if this stopped and there was peace.

“I’ve been suicidal all my life. It’s been one of the longest suicide attempts in history, me trying to drink myself to death. This life destined me to hang on the end of a rope and that’s what we have to avoid for our kids. Quality time and decent advice can save a life and save so much more.”

Barnes says he accepted the invitation to Canberra because of the work Menslink does to rescue troubled young men and throw them a lifeline. The morning’s event was hugely successful, raising the funds that support the majority of the intensive work they do with troubled boys and young men including mentoring, group support and help for families.

“I was self-destructive and destructive of everything around me because of my childhood,” Barnes said. “That highlights the work that people in this room are doing to help young men like me and their families to avoid a wrecking-ball life and all the grief and cost to the community that causes.”

Barnes told the crowd he wore a leather jacket to the breakfast to remind him of the jacket he wore “day and night” as a teenager. “It would protect you if you rolled in broken glass, or if someone tried to stab you, or you were in a brawl on the street. It would keep you warm if you ended up sleeping in a gutter somewhere”, he said.

Jimmy Barnes lauds Menslink’s lifesaving work for young men

Rock and roll hero Jimmy Barnes – Official was in Canberra to help Menslink raise funds for their work with troubled boys and young men, a cause that resonates deeply with his own troubled childhood. He spoke with Region group editor Genevieve Jacobs about a tough childhood and a big heart. http://ow.ly/ms1h50wcT51

Posted by The RiotACT on Tuesday, September 17, 2019

Writing two biographies, Working Class Boy (about his childhood) and Working Class Man (about his adult years) excavated a huge amount of buried pain for him. “I started writing and realised I was writing for myself, more than anyone else. I’d been running away all my life,” he said.

“There was a lot of stuff that not only had I not spoken to anyone about, but I’d also pushed to the back of my head and some things that I’d completely blocked because I didn’t want to remember. They were the things that had been killing me for 40 years,” he said.

Barnes said his life changed the day he sought help from a counsellor.

The “stuff” included physical, emotional and sexual abuse, the latter at the hands of family friends. Barnes’ father had been a featherweight prizefighter and his mother was just 16 when they married. By the time she was 21, she was raising five kids in a Glasgow slum where alcohol and violence were prolific and life was brutal.

But moving to Australia only transplanted their problems. In Elizabeth, they were surrounded by families from home.

“We brought our problems to Australia and there they festered,” Barnes said.

The lesson from his father was that you dealt with problems by knocking them down.

“Anyone who joked about our clothes from the Salvos, we punched them. My father and mother had parties where there was so much violence that my older sister would hide us in the cupboards to keep us safe and wouldn’t hear them bashing each other.

“Broken glass and smashed furniture was a common event in our house. We were always hungry and always afraid. We were unstable children.”

Singing brought the young Jimmy some approval and security at school. Later, he inherited an unlikely, gangling, quiet, cardigan-wearing stepfather called Reg Barnes whom he calls a saint. Reg showed him, for the first time, what security and consistency looked like in an adult.

There were a few other teachers who saw the good in him, an aunt who rescued him and took him home.

“They gave me a window of hope that could keep you going for so long. I found those windows all through my life.”

In rehabilitation for massive alcohol and drug addiction, he says the pain eventually started to drop as he faced his demons front on for the first time. He now thinks that skills, like reinforcing self-worth and checking on your internal dialogue, should be taught in our schools.

“As [Menslink CEO] Martin Fisk said, problem boys will become bigger problem men and families. The beauty of Menslink is that men don’t talk, it’s a sign of weaknesses if you ask for help. The day I manned up, the day I felt I really had courage was when I asked for help.

“I thought for years that if you see a counsellor, you’re a lunatic. But that was the day I became truly courageous and my life changed.”

You can learn more about Menslink and support their work here.