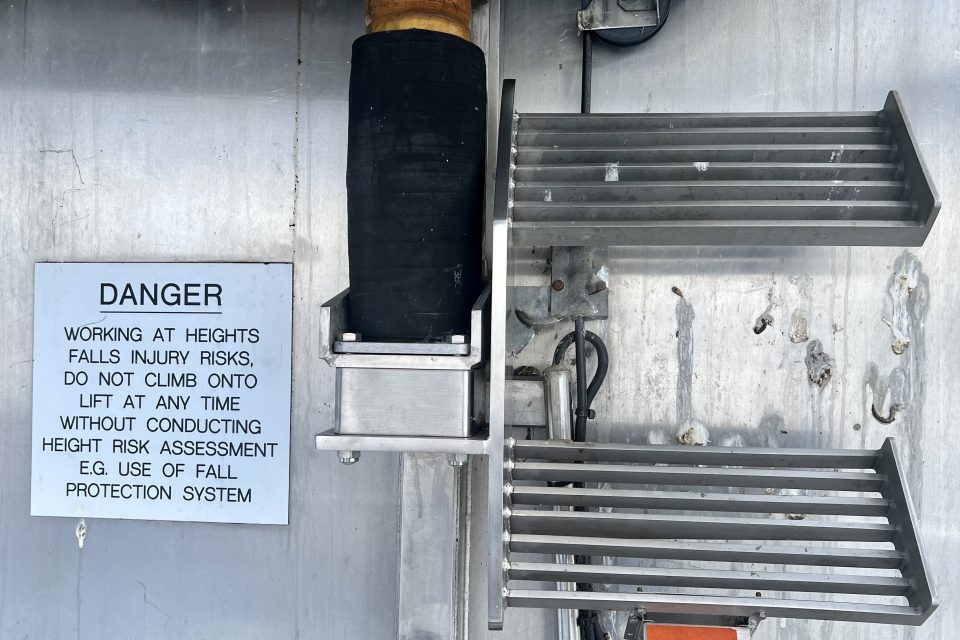

Stephen Doyle and Nick Harris ready to board the lift that takes them to the top of Parliament House. Photo: James Coleman.

All of the buildings in the centre of Canberra must top out at no more than 14 storeys, or 617 metres above sea level. And that’s not just an arbitrary number spat out by a dice roll at a planning meeting – it’s so Stephen Doyle and Nick Harris remain the highest workers in the city.

Every four weeks or so, the national flag atop Parliament House begins to look a bit tatty from the extreme winds found at 604 m above sea level. Stephen and Nick are among a handful of people in the world qualified to change it.

“You have to be a tradesman, either a mechanic or an electrician, and have certificates for working at heights and handling flags,” Nick says.

“It’s one of the most dangerous jobs in Canberra, because it’s not like there’s an emergency rescue plan.”

The flag has been replaced hundreds of times since 9 May, 1988, when it was first run up to the top of the iconic metallic legs to its new home. The whole operation is normally completed within an hour, before 10 am, on the first Wednesday of the month. Provided the conditions are right – rain or too much wind and no one dares go up there.

“No one can trump our judgment on the weather conditions to have it replaced sooner, not management, not any of the parliamentary staff, not even the Prime Minister,” Nick says.

Stephen has 14 years of experience behind him and Nick eight, but all up, it takes five people to change the flag – two up at the actual flagpole, two on the bottom at the ropes and another overseeing the whole operation.

But the process starts much lower, in the basement of the building.

The flags are sealed in plastic bags in a locked storeroom, and despite the fabric being light and coarse to the touch – like canvas – each one is also bigger than the side of a double-decker bus (12.8 by 6.4 m) and weighs 22 kilograms.

Because they also cost about $5000 each, the old ones aren’t simply thrown away either.

The Union Jack end remains largely intact, so after removal, a flag is sent to a Melbourne company that cuts off the tattered end and restitches a new end onto it. It’s back in the storeroom within a matter of weeks. Using this method, a single flag can last up to five years.

Once they’ve signed three different health and safety forms and girded themselves with harnesses, Nick, Stephen and the rest of the flag-changing team head to the roof.

Nick and another technician climb inside a trolley mounted to the top of one of the metal legs. This is winched along a narrow tram-like track at a painstaking pace to the uppermost of two small landings near the top. A drawbridge then folds out the side of the trolley to let them out.

“The trolley is only rated for 200 kg, so we have to watch what we’re carrying,” Nick says.

Down below, Stephen lowers the flag by winding in a rope that morphs into a metal cable and runs through one of the metal legs to the flagpole itself. Nick and his companion make the swap and the process is reversed.

One day, however, it all went wrong. Nick and Stephen were in the trolley when it ran over its own power cable and – in a flash of blue – severed it.

“About 70 m of power cable falls to the ground beneath us, while Stephen immediately climbs out of the little manhole on top of the trolley roof to see what went wrong. The reel of cable is slapping the roof of the trolley violently. It was scary. It’s not like we could just climb down either, or get a helicopter [we can’t risk the blades getting tangled in the flag].”

The trolley made it back down, but left its occupants with a renewed lack of trust in the machinery.

Occasionally, however, they have to go even higher.

Parliament House staff receive the occasional complaint about the flag, particularly when it’s flying half-mast at times of national mourning (as it was recently for the Queen’s death). Many say it looks like it’s only flying at one-third mast, but there’s a good reason for this, which Stephen describes as a design flaw.

“If it’s too low, the end of the flag can get caught on one of the four jutting tops of the metal legs and we then have to physically go up there, climb a ladder, and free it,” he says.

“In reality, the flagpole is too short.”

National flag protocol dictates that if a flag is displayed 24/7, it must be illuminated at night. This means changing the odd lightbulb up there, too.

Nick also recalls going to the top in another, smaller lift mounted to the side of the flagpole itself. While height training goes some way to helping, his knees were knocking the whole way, nearly as much as the pole was wobbling in the wind. On the plus side, there were the views.

“I saw these amazing, 50-cent-coin-sized black burn marks on the round top of the pole, from when lightning has hit it. I’ve never seen anything like it – it blew my mind.”

It’s something Stephen and Nick appreciate about their occasionally terrifying job.

“It’s nice to stand up here and appreciate the views, because we’re at the heart of Canberra – everywhere you look, the roads are straight,” Nick says.

Stephen adds: “Especially on Anzac Day, when we’re raising the flag to start the beginning of the dawn service. We get to stand up here and watch the sun rise.”

View or not, we salute you, gentlemen.