Dr Fiona Walsh: ethnoecologist, photographer and film-maker. Photo: Tibor Hegedis.

Dr Fiona Walsh has qualifications and expertise in botany, zoology and anthropology specialising in ethnoecology. And yet, working alongside First Nations people for the past 35 years, she’s always the student.

“I have always worked at the interface between people and physical environments,” she says.

“But even as a scientist, I knew I was among people with deep time knowledge that comes from generations living from the land, knowledge that is older and deeper than western science in Australia by orders of magnitude.”

Over decades, Dr Walsh has witnessed the intersection between millennia-old First Nations knowledge and modern science play out numerous times.

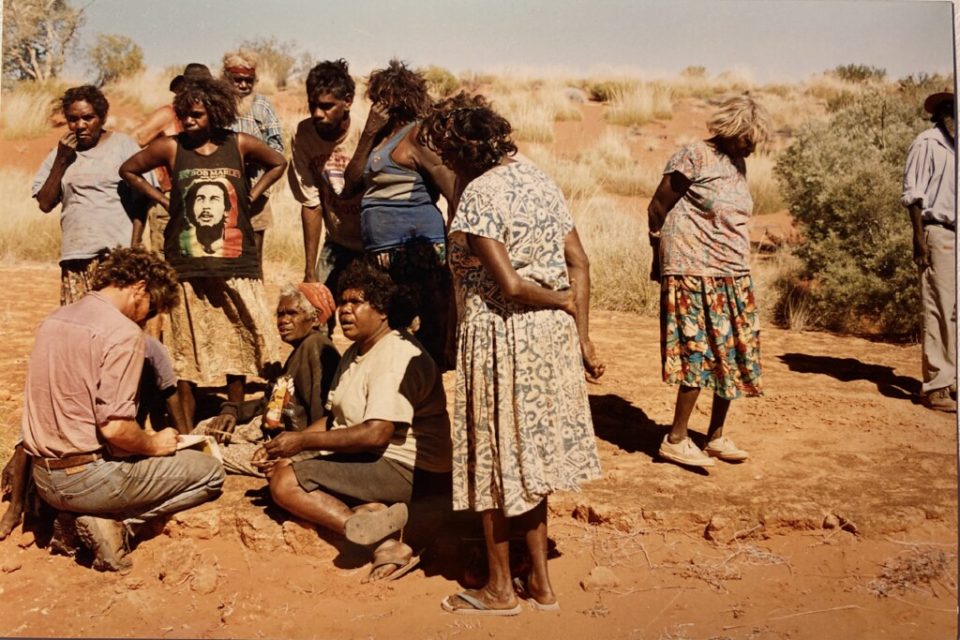

On a termite pavement, Nganyinytja lines a seed threshing pit she dug in a putu (pavement). Photo: Fiona Walsh.

She recalls that while in Western Australia, an international debate arose around ‘circle patterns’ occurring in the east Pilbara.

The circles were bare, hard areas of red earth surrounded by spinifex hummocks – a dense, prickly grass able to grow on the infertile soils across about 20 per cent of the continent.

The debate, expanding from Namibia and Angola to Australia, was around the factors contributing to these spots – why was the grass not growing on them?

A group of German-Israeli-Australian scientists had gone to the east Pilbara to investigate. They concluded the spots occurred when the vegetation organised itself for the efficient distribution of water and nutrients. But the traditional custodians of the land – the Martu people – knew better.

“They showed me that these hard, roundish areas were the homes of termites that lived underground. Martu knew that because women used the hard surface for various purposes, like threshing the seeds from which they made damper to feed their families,” Dr Walsh says.

“Martu people also spend a lot of time digging and looking for their foods, so they have a good knowledge of subterranean life as well as above-ground life.”

The findings of Dr Walsh with Martu, Warlpiri and scientist co-authors were published in top international science journals. Their findings have ecological implications that allow for informed landcare decisions in these vast swathes of land.

For example, the termites are a key to the survival of many desert reptile and birds including a nationally threatened species of lizard. The grass is a main food source for the termites, which are in turn an important food source for the Great Desert Skink.

“We’ve been able to bring it to the attention of zoologists who are studying that animal about features of its ecology that relate to the termite pavements and the habitat distribution of the skinks,” Dr Walsh says.

“A Warnman man, Purungu Desmond Taylor, co-authored a narrative of the Great Desert Skink, which the Martu people call Mulyamiji, and told of how when birthing its young, the female comes up to rainwater that’s standing on these hard termite pavements and live births young in that standing water.

“Martu and other desert people’s knowledge informs understanding of factors that shape the distribution of the Great Desert Skink and the conditions they need to breed – and much of it has been new to science.”

When people think of how First Nations knowledge relates to landcare, one of the first examples that comes to mind is the proactive practice of using small, contained spot fires to promote foods and help in hunting and gathering. These burn patchworks prevent more devastating wildfires.

With record high average global temperatures, sizzling heatwaves in the northern hemisphere and an ill wind predicted for Australia’s drought and bushfire-prone regions, Aboriginal burning practices will again enter the spotlight as the warmer months approach.

This, and other topics will be covered during National Science Week when Dr Walsh joins Merningar yorga (Menang woman) Shandell Cummings at the fourth of the Australian Academy of Science’s 2023 public speaker series Looking Back, Moving Forward.

Part of National Science Week, the discussion titled Caring for Land and Country looks at how the intersection of Indigenous knowledge with non-Indigenous science informs our understanding of land management, caring for Country and more.

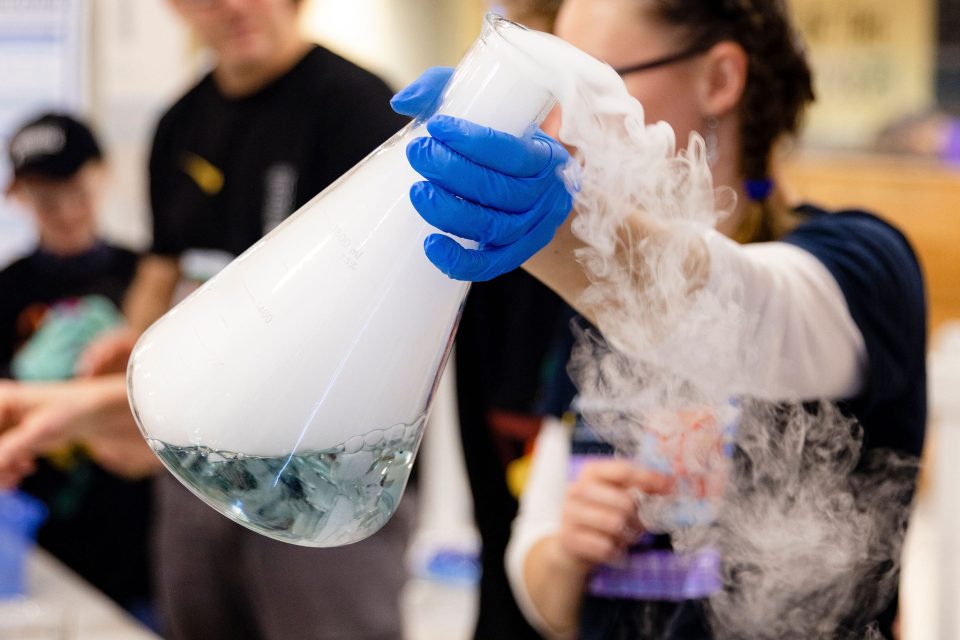

From 12 to 20 August, National Science Week will bring an array of fascinating activations, lectures, panels, workshops and events to the nation’s capital.

There’s something for all ages and interests. From a geology tour of Parliament House to a neuron knitting workshop and exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, science film screenings at the National Film and Sound Archive, activations at major shopping centres across Canberra, interactive science experiments and open days at ANU, and the chance to meet scientists and discover more about their fascinating work.

Looking Back, Moving Forward: Caring for Country takes place on Tuesday 8 August from 5:30 pm to 7 pm at the Australian Academy of Science, The Shine Dome, 15 Gordon Street, Acton. Tickets are $15 or free to watch online – book here and make sure you check out the full Science Week 2023 program in the ACT.