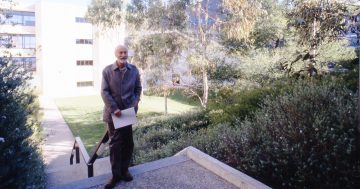

Good lighting makes these Brutalist buildings look far more inviting. Photos: John Jovic.

It’s rarely love at first sight with Brutalist buildings, and for many Canberrans there’s still no romance. The style is an acquired taste that plenty of locals still spit out.

Many find it foreboding, cold, depressing, totalitarian. As a chap on The Canberra Page said of Campbell Park Offices: “Always thought that [they’d] feature in one of those movies where the Nazis won WWII”.

But to be clear, what is Brutalism? All post-war concrete buildings that look like a pistol-whipping is going down inside?

There are frontiers where scholars skirmish but, at its essence, it’s a Modernist architectural style where heavy, geometric form results from chasing function. Brutalism’s raw concrete, glass, and brick. It’s the opposite of leering gargoyles or porticos trying to hide something.

It doesn’t hide anything. The term ‘Brutalism’ derives from the French term beton brut, meaning raw concrete, and not from the dystopian regimes we suspect it represents.

It fell out of fashion globally in the 1980s, but not before it visited Canberra.

Russell Offices: raw concrete on show. Photo: John Jovic.

When it did, David Bate was working at the National Capital Development Commission. A project manager who helped plan the High Court and National Gallery of Australia, he told us the commission was keen to have “Australian architecture of different styles”.

Unsurprisingly, he’s a fan of our Brutalist landmarks. He finds it’s ironic we sometimes view them as grim and oppressive, when they actually facilitate welcoming open spaces.

“With the gallery, one of the requirements was to have big open spaces with no columns, and when you’re building multi-storey buildings that becomes difficult,” he explains.

“They had a geodesic-type ceiling, so if you ever go there and look up, you’ll see this sort of triangulation in the ceiling. That’s designed so it’ll take the weight without the columns.”

Inside the National Gallery of Australia: make sure you look up. Photo: John Jovic.

He says a gallery’s function precludes too many windows, but if you go to the corner where the cafe is located, “you’ve got glass overlooking the sculpture garden. It gets the sunlight throughout the day and it’s a very pleasant space to be”.

It’s the same with the High Court.

“On the lake side of the High Court, your first reaction is to this huge structural wall of concrete.”

This side of the High Court building is the definition of transparent justice. Photo: John Jovic.

“But when you get into the building, what will hit you is the openness. It’s a huge ceiling height.”

John Jovic is an interstate fan of Canberra’s Brutalism. He enjoys our Brutalist buildings more than we do. In fact, when I suggested a lot of Canberrans didn’t like the buildings, he replied many Parisians also hate the Eiffel Tower.

While he finds the buildings “works of art” in their own way, he acknowledges they’re not conventionally beautiful. “They’re fascinating,” he says.

“I can look at a Brutalist building seemingly forever and learn something new about it almost every time.”

He wonders if this is half our problem.

“An interesting line of thought says that our perception of ugliness often comes from a fight-or-flight response. Those things that you don’t understand, threaten you.

“You can rarely look at a Brutalist building and understand it immediately: you often need to figure out ‘why does this bit jut out here? What is that doing?’”

He says if you stand in front of a building with someone who dislikes Brutalism, you can explain “that’s actually the service lifts that’ve been hidden through this external structure; it’s part of the function of the building”.

John also reckons we’re coming round to them, possibly with the help of Instagram.

“With any architectural style, there’s always decades where pretty much everyone hates it, or it’s ignored and that’s the time it’s most vulnerable because it gets knocked down.

“But there comes a point where people look back and go ‘sh*t this was actually pretty amazing’. It happened with deco. It happened with Victorian style.”

Fine. We should look deeper at Dickson Library then. But what if we still find it irrefutably grim?

The Australian War Memorial Annex. Photo: John Jovic.

One commentator wrote that Brutalist buildings could “engender feelings of unknowing, of mystery, and sometimes, especially when said Brutalist building is in disrepair or photographed at a particularly menacing angle, of fear …”. Perhaps, as something different, we can relish those responses too.

The fact it’s something different is ultimately the point. You wouldn’t want a whole city of Brutalism, David says. Fortunately, we don’t have one.

“In Canberra, you don’t get Brutalist buildings in isolation. You see them in terms of the landscape they sit in, and in relation to other buildings. If you compare them to say, the Treasury building or Old Parliament House and East and West Block; it’s a different style but they all represent the style of the day.”

One of Oscar Wilde’s characters said “architecture tells us a lot about our nation”.

Whatever indictment that has for the uninspiring homogeneity of Gungahlin aside, if it’s true that a drive through Canberra’s leafy centre will show some art deco, a smattering of Stripped Classical, and a few chunks of Brutalism, then we can say one thing for the nation’s capital.

We’re at least interesting.