Hannah Quinlivan, Shroud III, 2020, acrylic and aluminium, 320 x 200 x 40cm, Photo: supplied

Hannah Quinlivan’s art is all over Canberra.

It is in many of the capital’s light rail stations. It once dominated the foyer of the National Portrait Gallery. The new Canberra Hospital expansion features her ‘Life Force’ installation, and she is presently working on a major commission for the National Arboretum.

It is difficult to characterise her art. Her works are like immersive installed environments with rhythmic swirling linear masses that marry mood and temperament with movement and space. In their resolution, the pieces are not figurative but are frequently born of their environment – they need to be experienced rather than described.

The challenge of a show in a commercial art gallery for an artist who usually works on large-scale installations in dedicated public spaces is considerable. The pieces, although quite large, appear almost like miniatures in scale when compared with her usual work, and whereas most of her commissions are site-specific, the ones in the gallery are designed to be compatible with any domestic or commercial space.

Hannah Quinlivan, Katabasis II, 2024, powder-coated aluminium, 125 x 74 x 36cm, Photo: supplied

Quinlivan practises what could be described as spatial drawing. It is an art form pioneered by such sculptors as the Spaniard Julio González and later by the American sculptor David Smith, who made his famous welded spatial drawings in steel.

For her materials, Quinlivan gravitated to steel and aluminium wire, steel rods, powder-coated aluminium, printed ribbons, tape, acrylic and LED lights. We do not experience the raw qualities of the materials. For instance, the strength of steel, the pliability of acrylic or the lightness of aluminium, but rather the effect they have on the viewer after they have undergone the alchemy of the artist’s manipulation.

Many of Quinlivan’s pieces combine the sense of awe and mystery with what could be termed a dramatic gesture. Her Nocturnes series appears as dramatic suspended forms with an ambiguous relationship between the LED lights and the mysterious surrounding dark masses. I saw it in daylight and can only assume that they would appear quite stunning at night.

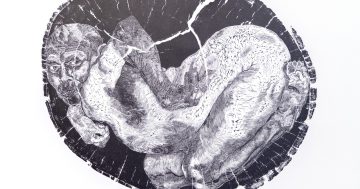

Quinlivan’s Katabasis II, woven with coils of powder-coated aluminium and, I assume, alluding to a journey to Hades, has a lovely intricacy despite the simplicity and transparency of its means of creation. What I enjoyed about many of the pieces is their ability to slow down the viewer with what could be termed effective ‘eye candy’ and then encourage them to enter a meditative state.

Hannah Quinlivan, I want you to remember (no 3), 2022, acrylic, aluminium and LED lights, 164 x 136 x 22cm, Photo: Supplied.

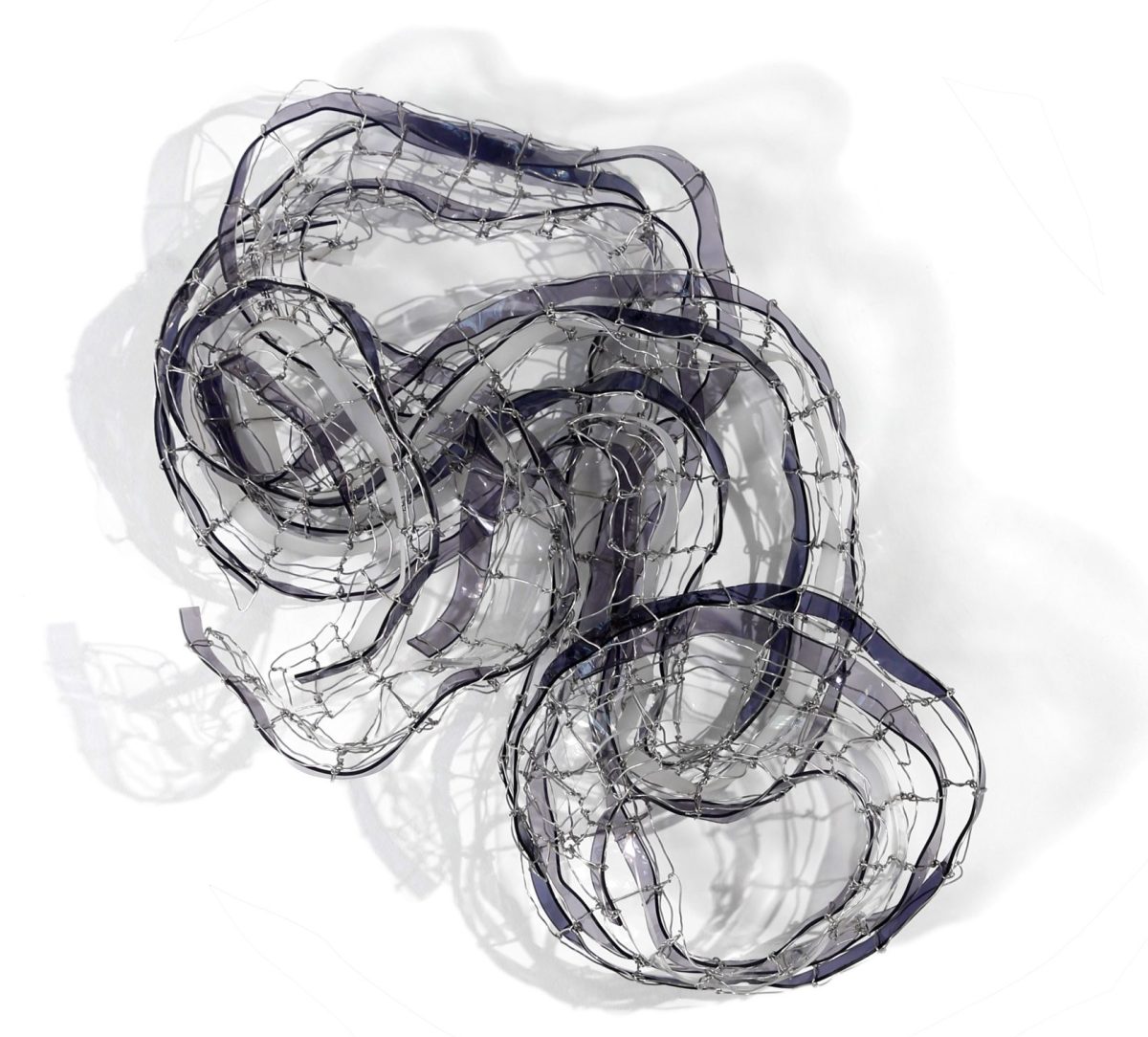

In the more complex pieces, including I want you to remember (no 3), where acrylic, aluminium and LED lights are interwoven into a bold pattern and occupy a sizeable wall space, there is a rhythmic intensity in the work. It draws you in and encourages you to stay and explore the created space.

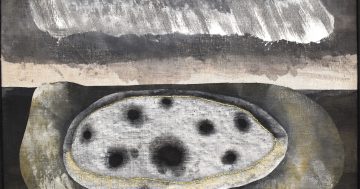

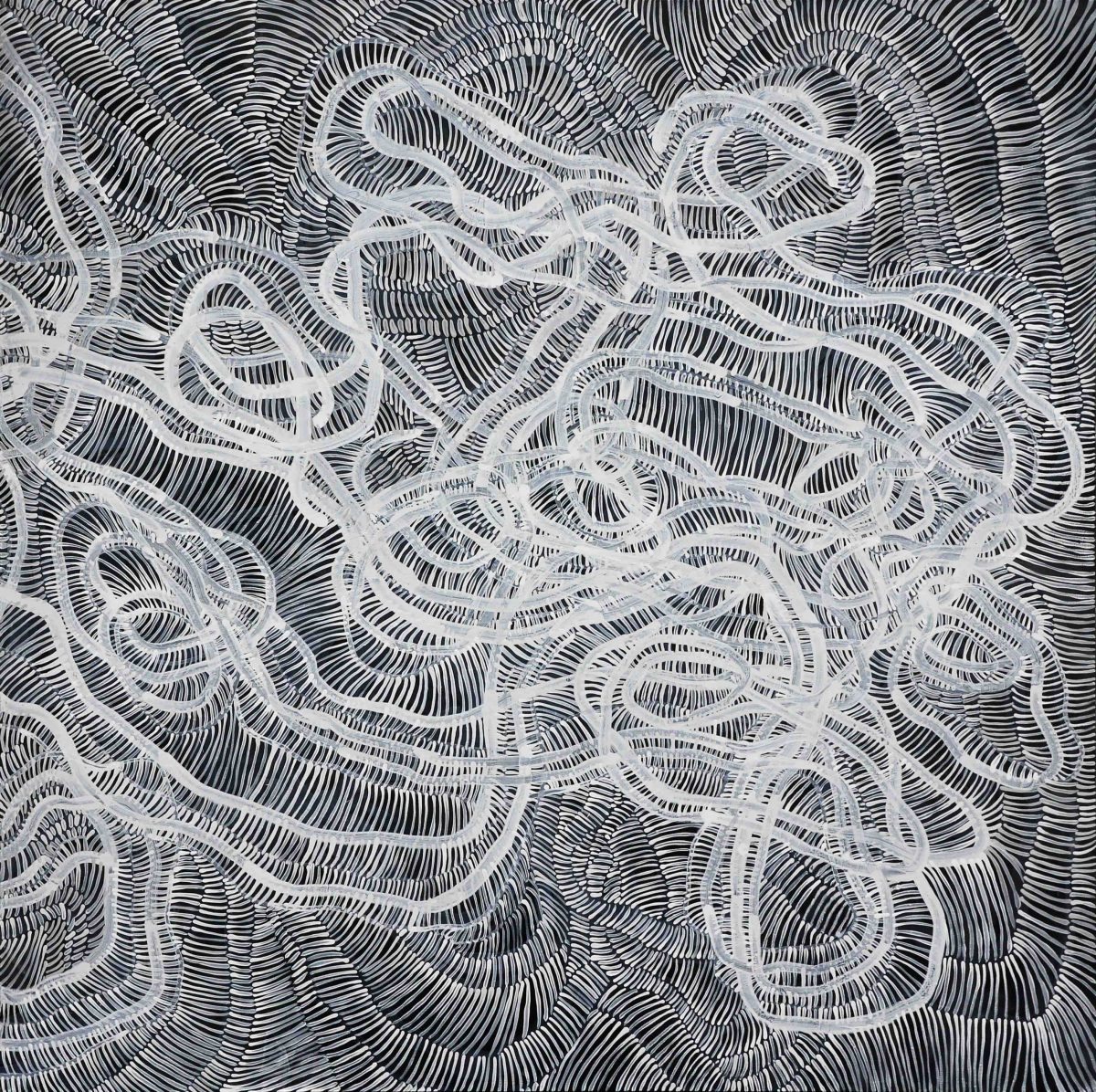

The Ecdysis series pieces are smaller in scale and less ambitious in their combination of materials but are very effective in their play with the created shadows. A similar comment may be made concerning the very large Shroud III piece that brilliantly commands its space and, through its intricate and rhythmic structure, holds you spellbound.

Hannah Quinlivan, Ecdysis I, 2024, acrylic and aluminium, 70 x 70 x 15cm, Photo: supplied

I found the two-dimensional paintings in the exhibition less satisfactory.

Smokescreen, an acrylic and ink-on-linen painting, is possibly the most successful of the bunch; however, when compared with sculptural installations, the surfaces have only a two-dimensional vitality. Without the presence of shadows, which are such effective and kinetic life forces in many of her pieces, the surfaces of the paintings appear relatively dormant.

Quinlivan, although she turns 40 this year, is still an emerging artist who brings a sense of drama, excitement and vibrancy to her art. This is a rare opportunity to view her work within a commercial art gallery where the pieces are actually for sale.

Hannah Quinlivan, Smokescreen, 2022, acrylic and ink on linen, 150 x 150cm, Photo: supplied

Hannah Quinlivan, Resonance, is on display at the Grainger Gallery, Bldg 3.3, 1 Dairy Rd, Fyshwick, until 4 August. The gallery is open from Wednesday to Sunday, 11 am to 5 pm.