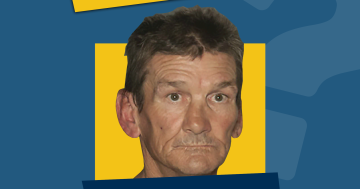

National missing persons. Clockwise: Katherine Ackling-Bryen; Gerardus Bakkenhoven; Renee Aitken; Elizabeth Barlow; Rhianna Barreau; Fredrick Bamboo; Zac Barnes; and Stephen Angel. Photos: Australian Federal Police.

In Australia, more than 38,000 people are reported as missing each year and about 2600 of those remain classified as long-term missing persons (missing for more than three months). Can ethical hackers or armchair detectives use the internet and social media to help the police solve these cases?

On Thursday (29 October), during Australian Cyber Week, members of the public will be given access to 12 real missing person cases and six hours to source intelligence and potential leads that could help solve their cases.

The Hackathon event will be headquartered in Canberra and is run by AustCyber in partnership with the Australian Federal Police, National Missing Persons Coordination Centre and Trace Labs, which trains people in how to use open-source intelligence to find missing people.

Participants will look for recent photos, the last known locations and social media accounts of the missing people from New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, Western Australia and Queensland. All leads will then be handed to the Australian Federal Police and National Missing Persons Coordination Centre.

Trish Halligan, a team leader at the AFP’s National Missing Persons Coordination Centre, says police face many challenges when trying to solve missing person cases and that open-source intelligence can help take the pressure off already stretched resources.

“I think crime television shows have a lot to answer for in terms of giving the families of missing people unrealistic expectations around the response time from police once they report someone as missing. Unfortunately, police aren’t sitting around waiting for missing person reports to be submitted, they’re juggling many jobs on any given day,” Trish said.

Trish also said that it’s difficult for officers to maintain the technical skills necessary to keep up with the ever-changing cyber world.

That’s where events such as Hackathon and open source intelligence come in and highlight the issue of missing people as a community issue and not just a policing issue.

Chris Poulter, founder and CEO of OSINT (Open Source Intelligence) Combine, said using people in a group setting to source intelligence from public resources allows analysts and investigators to spend more time on the critical part of connecting the dots between leads.

Members of the public can pull many leads in a short amount of time because they are not as emotionally invested in the cases as the police, which allows them to focus on the collection of intelligence rather than analysing the intelligence, Chris said.

“There’s definitely been a paradigm shift from the historical views of what open-source intelligence can provide,” Chris said. “Historically, there was a belief that if [the information] wasn’t secret, it couldn’t be of value, but the information society we live in now has demonstrated the value of open-source intelligence.”

Linda Cavanagh, the national network lead at AustCyber and founder of the Hackathon series, said the objectives of the event are to generate awareness of cyber-security skills, missing people in our community and the agencies that are supporting them, and to combine a crowd-sourced open-source intelligence effort with traditional policing methods on current missing person cases.

During the first Hackathon in October 2019, a total of 354 ‘ethical hackers’ – as Linda likes to call participants – and investigators gathered across Canberra, Sydney, Brisbane, Gold Coast, Sunshine Coast, Darwin, Perth, Adelaide and Melbourne to generate 3912 leads on 12 long-term missing persons cases.

One of the missing person cases was that of ACT man Jean Policarpio who was last seen leaving his family home in Bonner on 26 September 2017. His father came along to the event to see hundreds of people looking for leads to find his missing son.

“He was in awe and so humbled that there were people who cared about his missing son,” Linda said.

Not only does Hackathon give hope to families, but the event also re-energises and inspires the police officers assigned to the missing person cases, according to Linda.

“We make sure we have the relevant case officers and police officers there. By the end of the [2019] event, everyone was hugging and kissing – obviously, we didn’t have the social distancing restrictions that we have now,” she said.

Trish said there are many reasons why more than 100 people go missing every day.

“The reasons for going missing can include conflict, mental illness, miscommunication, dementia-related illnesses, misadventure, people trying to escape domestic or family violence or being a victim of crime, so anything from a young person running away to an elderly person suffering from Alzheimer’s disease who goes for a walk and can’t get home,” she said.

For information, visit the National Missing Persons Hackathon.