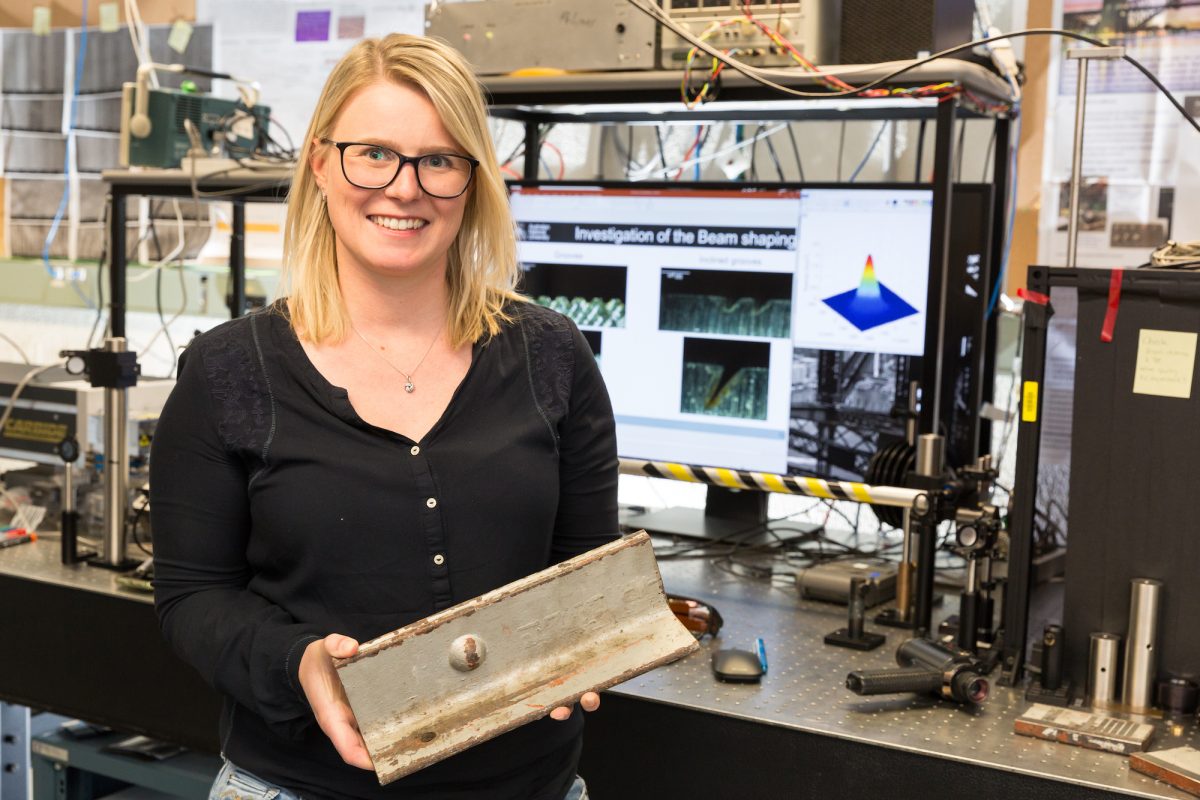

ANU physics PhD student Victoria Zinnecker holding a piece of Sydney Harbour Bridge. Photo: Dave Fanner, ANU.

This July marks 101 years since work started on the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

But the work has far from ceased.

A dedicated team of about 120 people, including engineers, painters, carpenters and riggers, spend a combined 19,000 hours each month on maintenance.

There are more than 6 million hand-driven rivets to check, and a total steel surface of 485,000 square metres to paint, with each one of four coats requiring 30,000 litres of paint. The final coat is done in the now heritage-listed ‘Sydney Harbour Bridge grey’.

More than 250 km away in Canberra, a team of researchers is also working on a way to ensure the bridge remains sturdy for another 101 years.

After all, the conventional way of sandblasting away old paint and dirt to keep the big steel coat-hanger looking smart works for most parts, but there are about 7 km of internal tunnels too small for humans and, therefore, the sandblasting equipment.

The result is the bridge is slowly rotting from the inside.

HMAS Canberra I passes under an incomplete Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1930. Photo: Defence Archives.

Engineers from the Australian National University (ANU) and the University of Canberra (UC), together with the University of Sydney, the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO) and Transport New South Wales, have come up with a far more elegant solution.

Fire a laser at it, with a whole power station’s worth of energy behind it.

“A mammoth effort is required to look after the bridge, a large part of which is cleaning the paint and stone and replacing aging and damaged paint,” Professor Andrei Rode from the ANU Research School of Physics explains.

“The arch interior has not been maintained since the bridge was built over 90 years ago and is in major need of restoration.”

Cleaning the inside of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Photo: University of Technology, Sydney.

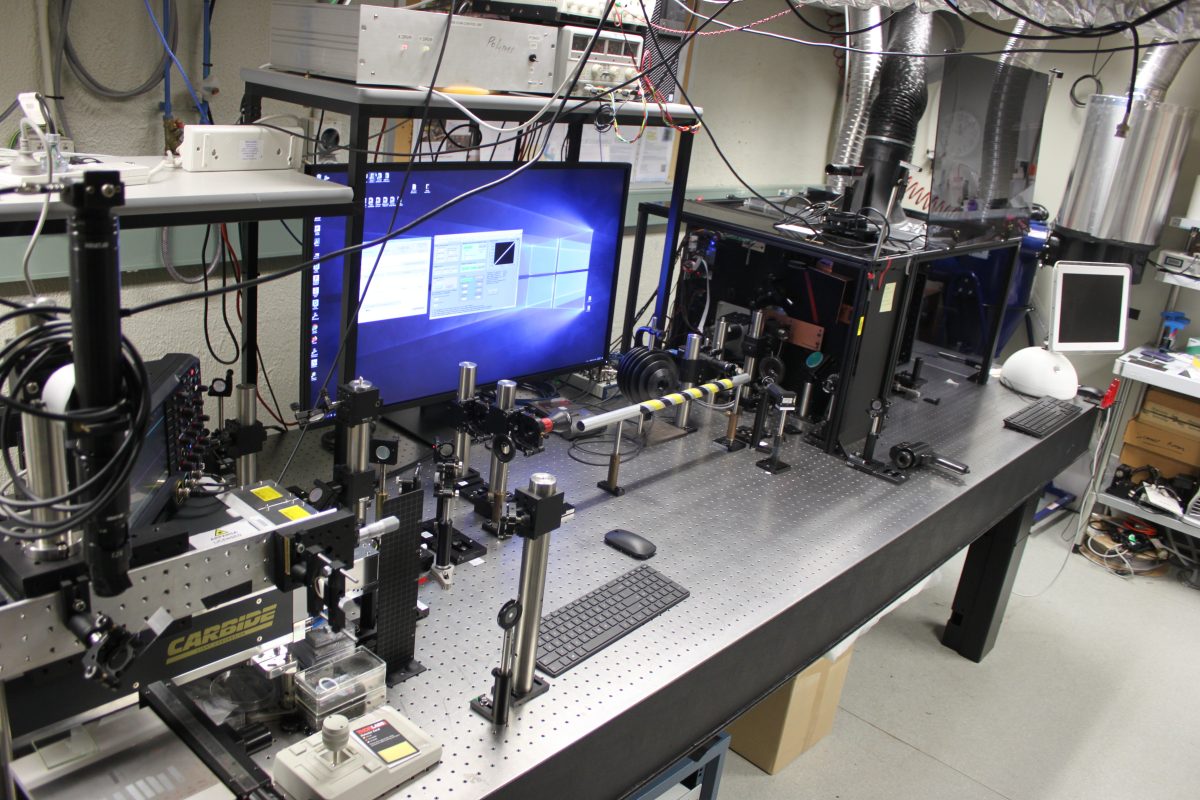

Using lasers to strip paint is nothing new, but up to now, they’ve been accompanied by a great deal of heat, so high it usually melts the steel’s surface.

The new ultrashort laser pulses are so powerful that they’re able to move on to a different section of steel before the steel has felt the heat.

“The laser pulse is about the output of an entire power station applied in less than one-thousandth of a billionth of a second,” the ANU’s Professor Stephen Madden says.

This sheer amount of energy “instantly evaporates” the paint and grime on the surface, leaving the underlying metal structure intact and cold.

UC’s Associate Professor Alison Wain explains it a different way.

“With a door, you push it open and the energy is distributed over the whole door. But with these new femtosecond lasers, it’s like shooting a bullet through the door.”

While the ANU team’s focus is on the steel, the UC team has been working on ways to apply the same laser to the bridge’s granite since 2019.

“The steel needs work for stability and strength, while the granite is more an aesthetic thing,” Associate Professor Wain says.

The bridge’s four pylons are made from 173,000 blocks of granite, extracted from a quarry in Moruya. Just like the steel, part of a “working bridge in the middle of a busy city”, they’ve been dirtied by a mix of air pollution, marine spray, and rust particles from the train tracks.

“The rails get a bit rusty overnight, and in the morning, the trains go past and and rust falls onto the stone and stains it.”

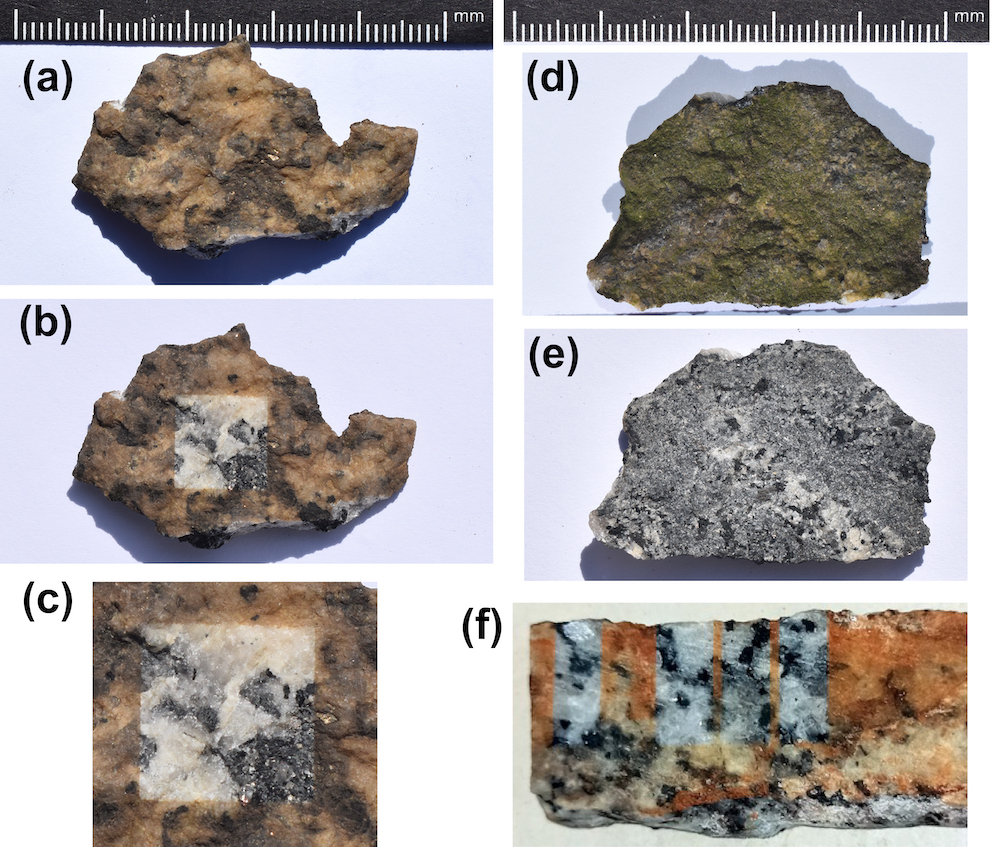

Sydney Harbour Bridge granite, before and after a laser clean. Photo: Alison Wain, ANU.

But while granite is the second hardest substance in the world behind diamonds, even it has its limits when a laser is boring down on it.

“The interesting thing about granite is that it’s actually a whole mix of different minerals, which is why it always looks speckled,” Wain explains.

“And so what we’re trying to do is establish this new technique won’t harm any of those materials, so we actually had to look at each one individually.”

The project has been lab-bound so far, but all that’s stopping it heading onsite is sourcing versions of the technology small enough to navigate the twists and turns of the bridge’s structure, not only of the laser itself, but also all the robotics that will govern its movements.

The laser cleaning machine has been lab-bound so far for testing. Photo: Alison Wain, ANU.

Wain estimates the project will begin in earnest in about three years’ time.

“But I think within the next year, we’ll have a demo of something that can go on the largest spaces of the bridge.”

And with more than 270,000 steel bridges across the US, Europe and Japan, and a global abrasive blasting market worth $11 billion, large-scale laser cleaning technology could transform the future of global infrastructure maintenance.

“The new technique has applications that go far beyond industrial processes,” Professor Rode from the ANU adds.

“It has, for example, also proven to be a cost-effective method for cleaning contamination from and restoring the beauty of historic architectural and cultural treasures.”