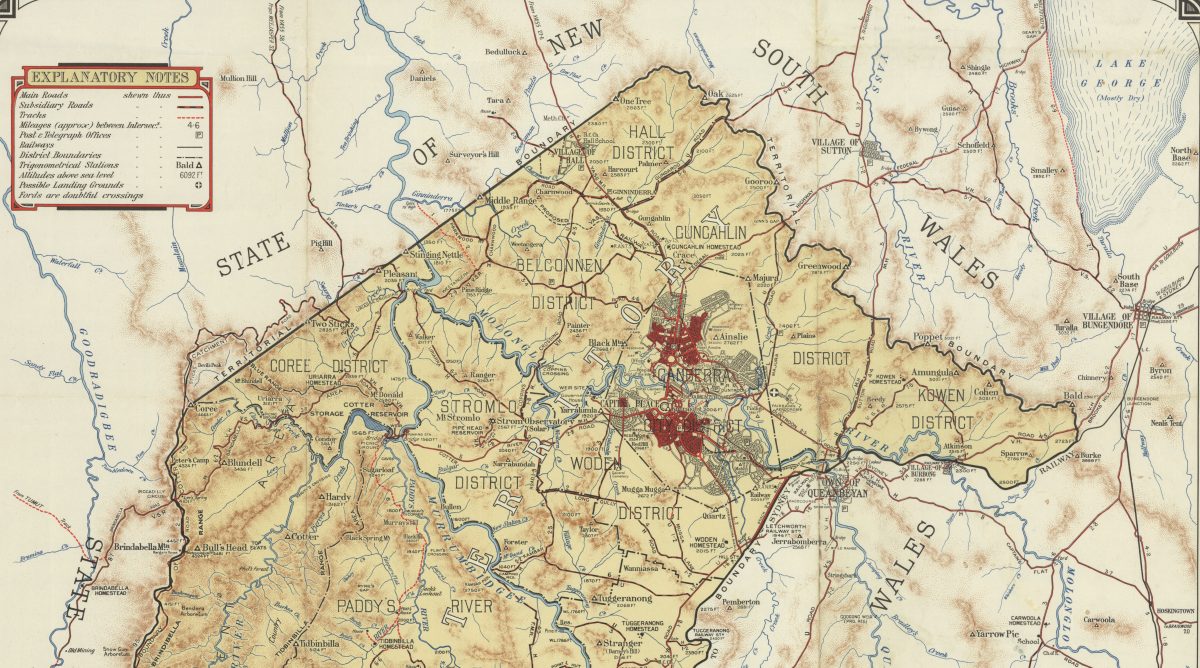

A 1950 map of the ACT compiled and drawn under the supervision of L Edwards, Chief Draftsman, Survey Branch, Engineers Department. Photo: ANU.

Last month, the Chief Minister announced plans for the first ACT border change in more than 110 years.

It all started when the local government bought two extra parcels of land off NSW in December 2021 for the Ginninderry development. Now they want to move the border so a new suburb of 5000 homes can be built within the Territory, to the west of Belconnen. This will be called ‘Parkwood’.

“I view it as just correcting a historical anomaly,” Andrew Barr said.

“It’s really a historical quirk that a straight line was drawn through the paddock rather than the river corridor, which is where the Territory border followed for most of the Western edge.”

What was he talking about?

Matthew Higgins is a Canberra historian and writer who has been digging into the history of the ACT border since the 1990s.

“That was when I became aware there were surviving original survey marks from the original survey out along the ranges, and I thought these must be sites of incredible heritage significance to early Canberra,” he said during a presentation at the National Museum of Australia in 2013.

“But hardly anyone outside the survey community seemed to know that they were there.”

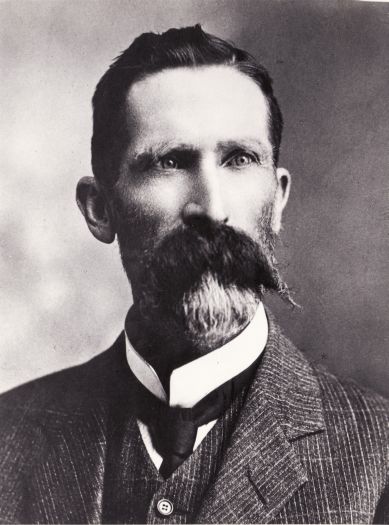

Canberra’s first surveyor, Charles Robert Scrivener. Photo: Canberra & District Historical Society.

Matthew set out on a survey on his own, determined to tell the story of how the ACT came to be the way it is today. Along the way, he found out the reason behind the 30 km straight line along the northwest.

But first, some background.

In total, the ACT’s border is 306 km long. Its highest point is Mount Bimberi, at 1911 metres, and its lowest is at 430 metres along the Murrumbidgee River, close to Uriarra Crossing.

All of this was first mapped out in 1909 under the direction of a very experienced senior surveyor from NSW, Charles Robert Scrivener. He was guided by one overriding factor – water.

“The federal authorities wanted the territory to contain the water catchment for the new city,” Matthew explained.

It turns out the previous century had been riddled with inter-state battles over polluted water coming into NSW. Scrivener was determined this same fate not befall the new Federal Capital Territory, “so water was at the forefront of Scrivener’s thinking in deciding where the territory should run”.

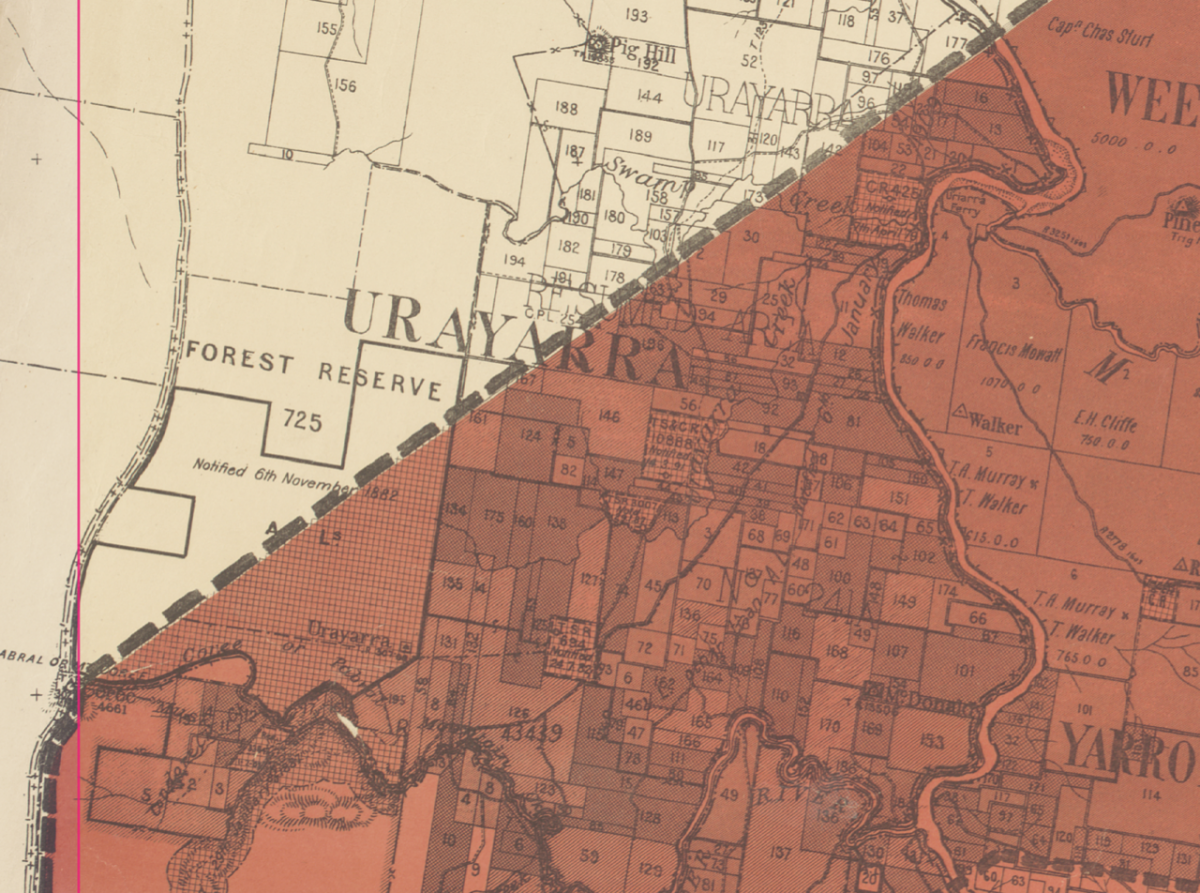

An excerpt from the map drawn by Scrivener showing the proposed boundaries of the ACT. Photo: National Library of Australia.

This is where the anomaly begins. Trace the ACT’s border on a map today and it will be squiggle and more squiggle, at least until you arrive at Mount Coree when the line suddenly becomes straight for 30 kilometres until it reaches One Tree Hill, behind Hall.

Despite all the emphasis on water, this line cuts off a part of the vital Cotter catchment – Coree Creek.

Over the years, Matthew said there have been many attempts to explain what happened, starting with the government running out of money to finish the job.

“All the rest of the border had been surveyed, so the government said to the surveyors, ‘Just run a straight line, she’ll be right’. It sounds great, but it’s false because, rather than being the last part of the border surveyed, that straight line was the very first.”

Matthew continued investigating.

“There was no way Scrivener had the resources to go out and physically walk the whole border,” he said.

“He was dependent on maps at the time, particularly parish maps of people’s land holdings, and they had several inaccuracies because there weren’t the resources to survey it accurately.”

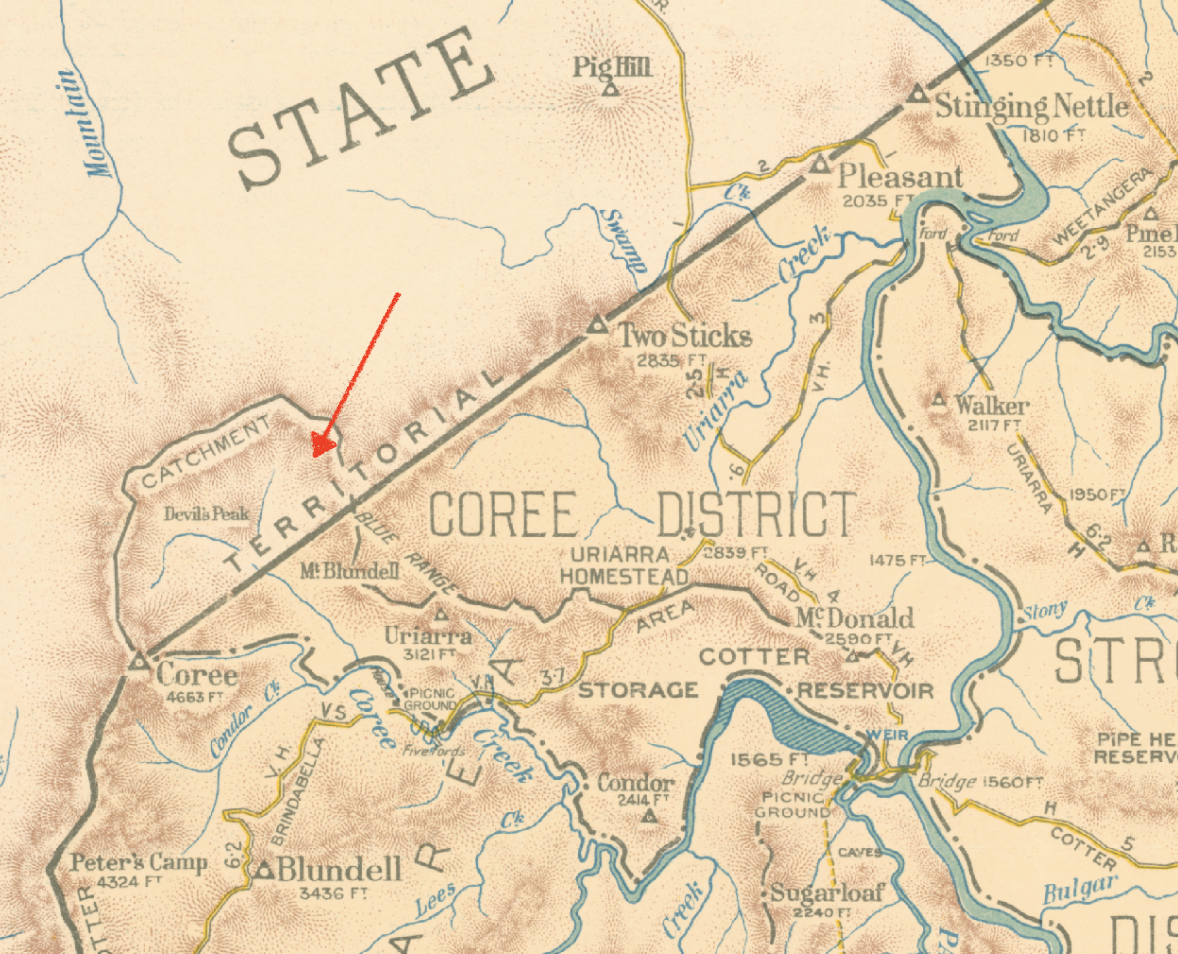

A later map shows Coree Creek flowing across the ACT/NSW border. Photo: National Library of Australia.

Sure enough, the original parish map of Uriarra has Coree Creek flowing inwards from the summit of Mount Coree. To Scrivener in his office, drawing a straight line would have incorporated it.

It wasn’t until 1926 that another surveyor went out so see the lay of the land and discovered Coree Creek started further back in NSW. But it was already too late.

“The Commonwealth didn’t change the border – that would require rewriting the legislation because the border is physically described in those 1909 acts,” Matthew said.

The safety of the water supply wasn’t guaranteed until the 1990s when NSW declared the surrounding area the Brindabella National Park. This finally ruled out development near Coree Creek.

“So that’s the answer to our Cotter catchment conundrum.”