Charley Carey spent 11 happy years with her husband, Harrison, before he died unexpectedly. Photo: Charley Carey.

In every known way, Charlene (Charley) Carey felt prepared for anything her husband Harrison’s epilepsy could throw at them. She attended appointments, spoke to GPs, did training and diligently documented his episodes.

On 5 February 2022, as she walked to her bedroom of her Banks home where she’d left her husband to enjoy a Saturday morning sleep-in, she felt the loss of him even before seeing it.

“My worst fear had come true, but not in the way I expected,” she said.

“It was always in the back of my mind that he could have a seizure at work or while he was riding his BMX and hit his head on the way down. I thought if something were going to go wrong, it would be in that way.

“I knew the cause of death had to be epilepsy, I just didn’t know how … I had spent more than a decade researching and talking to experts, but until the day the GP explained the coroner’s report to me, I had never heard the acronym SUDEP.”

Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy, or SUDEP, refers to deaths in people with epilepsy that are not caused by injury, drowning, or other known causes.

Little known yet devastating when it hits, about 300 people each year die from SUDEP in Australia.

“I know that number seems insignificant in the grand scheme, but those 300 people have families, kids, friends, workmates – a community of people affected by their passing,” she said.

“That’s 300 people who had a life to live prior to this, 300 people who were going to experience all the joy that was to come with birthdays, anniversaries and life, who no longer will.”

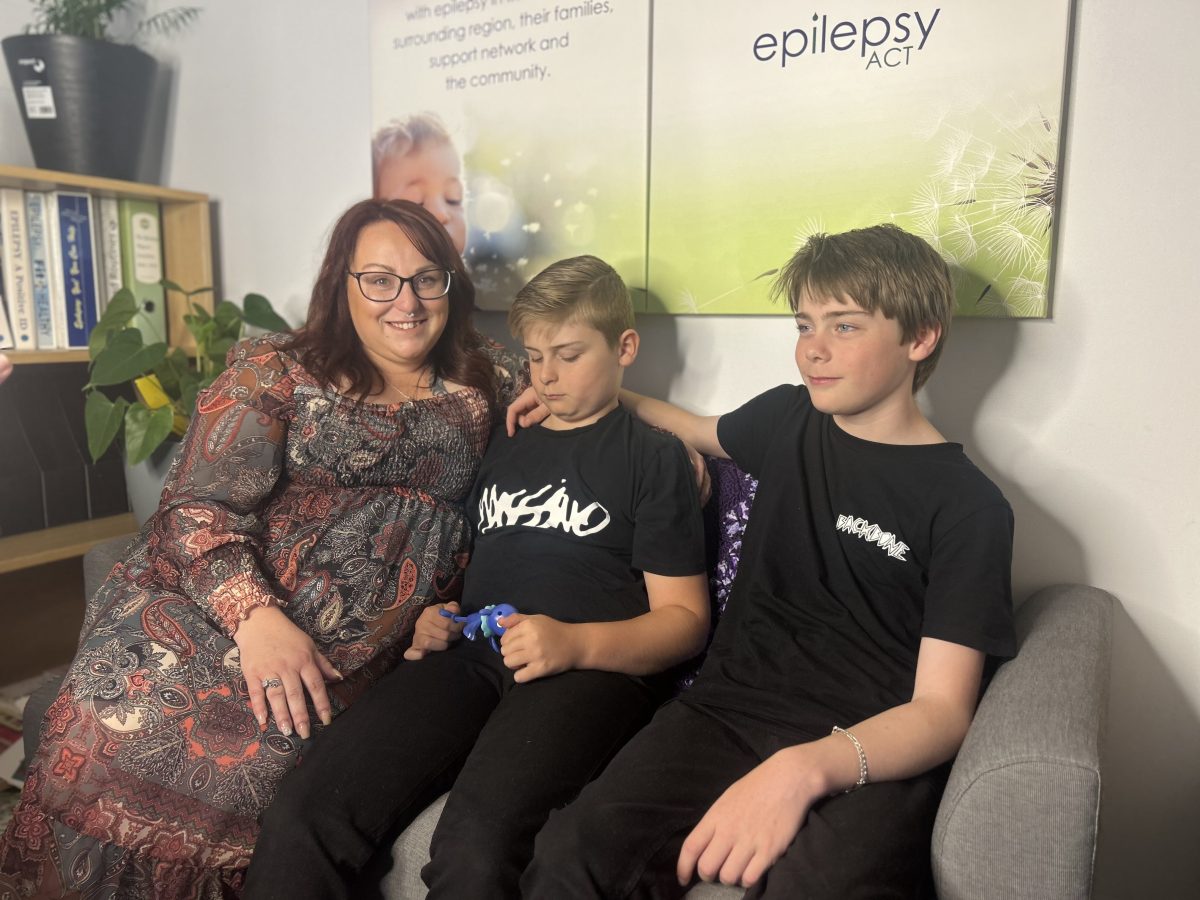

It’s been a steep learning curve for Charley, who is raising her two sons solo following her husband’s sudden death. Photo: Fiona Allardyce.

The unexpected death of Harrison triggered a steep learning curve for Charley and her two boys, Kaidyn (13) and Madden (12), but one of the hardest things to cope with was the shock.

She was told that medically, it couldn’t have been prevented. But Charley says that’s not to say nothing would be different if she had known about SUDEP.

“The ambulance was on the way, a woman was talking me through it as I gave him CPR and I remember saying to him, ‘I need you here, the boys need you here, so if you can hear me, if there’s anything you can do to come back to us, please come back to us’. The woman on the phone told me, ‘You’re doing all the right things’.

“Afterwards, the paramedic told me there was nothing else anyone could have done … Even the medical examiner told me he’d never met anyone so organised with administering medications and documenting seizures.

“I ask myself, had we been aware of the real risks, would we have done something differently? Could we have made every moment count, taken more holidays? Could we have had more of those conversations that we realise, only once we’ve lost a person, are incredibly important?”

These questions drive Charley’s new calling – raising SUDEP awareness.

“I don’t think anyone really fully understands the element of fatal risk in seizures themselves until you go through something you can’t come back from,” she says.

“We need to acknowledge this reality. If we don’t start the conversation, someone is never going to get to have that goodnight cuddle with their dad, a bedtime story read, someone won’t get to kiss their partner, won’t make the most of those moments we assume will be there every day.

“If I can help even one person start that conversation, it’s worth it. Because I am telling you from experience, the hardest conversation is the one you’ll never get to have.”

Charley and her boys will never forget Harrison. Photo: Fiona Allardyce

Wednesday, 18 October, is SUDEP Action Day, offering many ways to get involved. Mostly, it’s about having a conversation, but Charley is calling for more.

She would like to see epilepsy-specific training become more mainstream because general first aid doesn’t cut it in the event of a seizure.

“You could be walking down the street and have a seizure. Would a bystander know what to do? It could happen in a shopping mall – would staff know what to do?” Charley asks.

“Seizures can happen any place, any time. The triggers are numerous and varied, and how seizures are approached could be the difference between life and death.”

For more information, visit Epilepsy ACT.