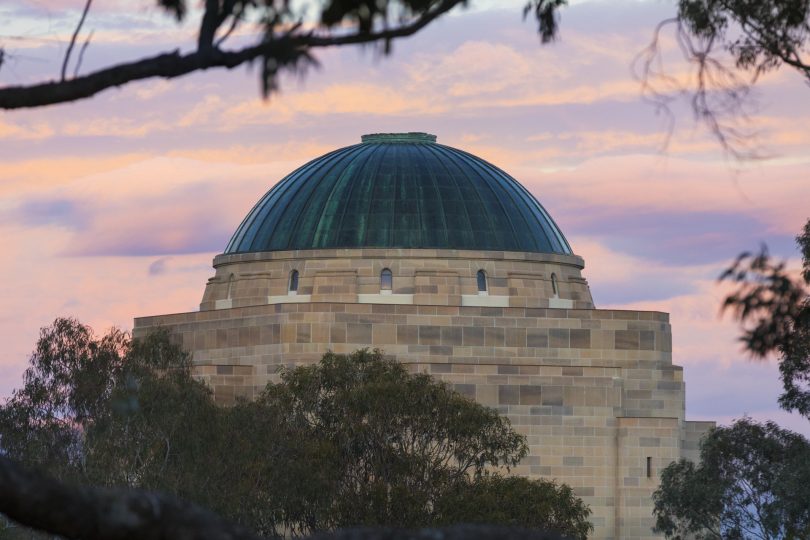

The Australian War Memorial: not enough questions have been asked about Australia’s recent war history. Photo: Michelle Kroll.

The revelations about alleged war crimes in Afghanistan by members of Australia’s Special Air Service regiment is a big wake-up call to those who have been drawn to the cult of the Digger in recent decades.

The Brereton report has shocked the Defence establishment and cast a shadow over an institution that has not just been held in high regard but revered to the point that any alleged wrongdoing is considered almost a slur on the national character.

It has divided the country, and is generating a backlash from veterans and their supporters.

As the son of a World War II veteran, you didn’t grow up in this country without being steeped in the culture of the returned serviceman and the sacrifice of those two great conflagrations.

The folly of Vietnam may have dented that image of the military and eroded the nation’s respect temporarily, but the recovery was swift.

When John Howard ended the Labor ascendancy in 1996, he assiduously cultivated the Anzac myth, wrapping his government in the flag, deploying troops to the Tampa to keep asylum seekers from our shores, and fatefully to Afghanistan as part of the US war on terror after the 9/11 attacks.

Where before there had been quiet, respectful understanding of the role of the military and of veterans’ sacrifices in defence of the nation, the Howard years began an amplification of Anzac and an uncritical lionising of the Australian soldier, and the nation’s experience in war.

Brave, fierce and unmatched in battle, a larrikin but generous and good-hearted, the Digger was always divorced from reality, and an impossible ideal to live up to, given his stock and trade.

Afghanistan and later Iraq has produced thousands of veterans as Australian soldiers rotated in and out of these theatres over the years, but it fell to the SAS to do the dirty work, particularly in Afghanistan.

Special by name and special by nature, these are elite troops selected and trained for the sharp end, proficient at killing the enemy in the most inhospitable of environments.

Apparently, their feats also commanded special attention and the SAS were raised to an exalted position in the defence pantheon that may have contributed to a belief by some that they were untouchable, possibly leading to the alleged extrajudicial killings in Afghanistan.

But continuous rotations and exposure to battle in a military terrain where there are no frontlines may also turn superheroes to the dark side.

These are the cultural and strategic coals Defence must rake over, and the soldiers involved deserve their presumption of innocence, but the Brereton report also raises issues for our political leaders and the keepers of the flame at the Australian War Memorial.

If politicians want to see the military and our veterans respected then they should keep their distance and encourage an honest appraisal of Australia’s involvement in war, which since World War II has been mainly as an uncritical ally of the US in theatres where the lines were often blurred.

The uncovering of alleged war crimes in Afghanistan, thanks to whistleblowers, the media and the integrity of Defence officials, is precisely why some have argued against former Memorial director Brenden Nelson’s push for the institution to expand so it can have the space to tell contemporary stories.

Engagements such as Afghanistan, they argue, need reflection and a passage of time in order for them to be portrayed honestly.

Dr Nelson, a former Defence Minister, becomes deeply emotional talking about the experiences of veterans and has been accused of being too close to the veteran community, including the SAS, to have a clear eyed view of their service.

Perhaps the Brereton report will offer an opportunity for people to take stock of our relationship with war and for the more ”gung-ho” supporters of the AWM expansion to reflect on their motives.

The other argument to be wary of is the ”few bad apples” thesis whereby the actions of a few should not reflect badly on the whole organisation.

Obviously, what may have happened in Afghanistan should not be laid at the feet of all our servicemen and women, but simply labelling the soldiers involved bad people ignores the culture that nurtured them, the crucible of war that tested them and institution which sheltered them.

These are deep questions being asked of our leaders, and of us as a people.

War may be hell, but it is exactly where our better angels are needed if the civilised values we extoll are to survive.