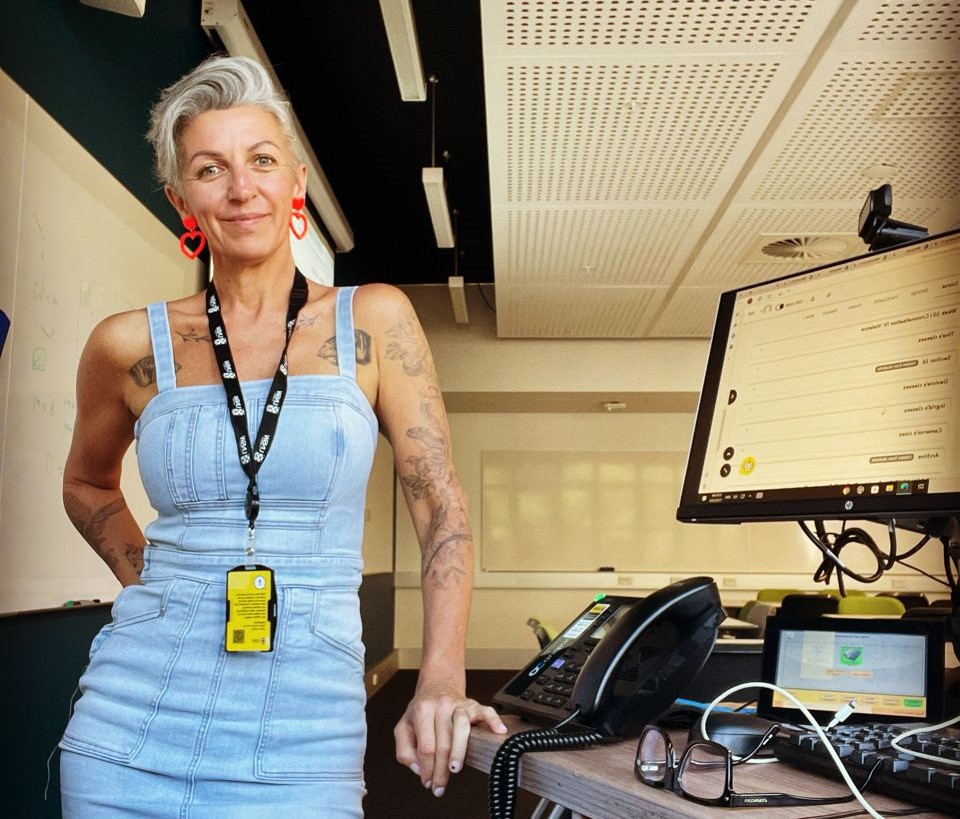

Tina McPhee is a “lived-experience criminologist, PhD candidate, abolitionist and language matters campaigner”. Photo: Tina McPhee, LinkedIn.

All up, Tina Louise McPhee spent five years in a women’s prison after pleading guilty to 181 counts of fraud in 2014.

She stole nearly $2 million from clients of her finance advisory business and spent the money on a luxury house, overseas holidays, designer clothes and even breast implants.

All these years later, however, she’s turning over a new leaf and using her experience with incarceration to improve the lives of others in Australia’s justice system.

She’s now the ‘lived-experience advocacy coordinator’ for a new pilot program launched by the Justice Reform Initiative (JRI).

“Prison was traumatic,” she says.

“Probably the most traumatic thing I’ve ever experienced in my life. I’ve got PTSD from it. I know how horrible prison can be – we think it’s this rehabilitative place, but for a lot of people, it’s a place of trauma and violence.”

The JRI was founded in September 2020 with a mission to halve incarceration in Australia by 2030.

ACT campaign and advocacy coordinator Indra Esguerra says it’s about “looking at all the moments where people end up in the criminal justice system and what diversions we can put in place at all those points” so they can avoid prison.

“When a judge has a case in front of them, instead of sending the person to jail, they could say, ‘Well, can you do a work order instead?’ or, ‘How about you go and spend two years doing a placement with a nursery?’, or another appropriate job to get people back on the straight and narrow.”

She says the ACT tracks “pretty well compared to a lot of other places in the country” and puts this down to its small size and the actions of a “progressive government”.

Around 400 people are detained at the Alexander Maconochie Centre. Photo: Michelle Kroll.

The ACT Government has a goal to reduce recidivism by 25 per cent by 2025, which would result in 146 fewer detainees returning to custody.

One of its first actions as part of this was to introduce the Drug and Alcohol Court in December 2019, which Indra says “looks at the intricacies of people’s addictions”.

An evaluation by the Australian National University (ANU) in 2022 found this “improves the social and health outcomes for participants” and “may have saved the community $14 million in avoided prison time”.

Then there’s the Justice Housing Program, which provides limited accommodation options to a number of alleged offenders, including women and Indigenous people.

“Releasing people from jail and putting them into homelessness is a surefire way for them to probably end up back in there,” Indra says.

She also praises moves to raise the age of criminal responsibility from 10 to 12 because “10-year-olds can’t possibly fathom what’s going on”.

“If you treat your dog really bad, it’s going to turn into a horrible, aggressive, defensive, aggressive little thing. And I guess that’s what we’ve been doing to children in juvenile detention centres. And we’re surprised when they end up in the adult justice system.”

ACT Policing is on board, too, and held a ‘Reducing Recidivism Roundtable’ in June this year to tackle a “complex problem with no single solution”.

Funded by a grant from Hands Across Canberra, JRI’s new pilot program will train 20 people with lived experience in prison – like Tina McPhee – so they feel comfortable telling their story to the media and lobbying politicians for change at a federal and local level.

Tina says the end result is not about opening the prison doors and setting everyone free.

“Pretty much every woman I was in prison with was in prison for punishment, not because the community needed protection,” she says.

“But for people who aren’t yet ready to heal and who also need protection from themselves, we need to make sure the place we’re putting those people is not adding to the behaviours that caused the harm in the first place.”

Indra says the ACT, with its relatively small size, is the perfect place to start justice reform.

“We’ve got just under 400 people in the jail here, and we can know them all by name and look at their backgrounds, so we can actually start supporting their families to change the direction of their trajectories.”