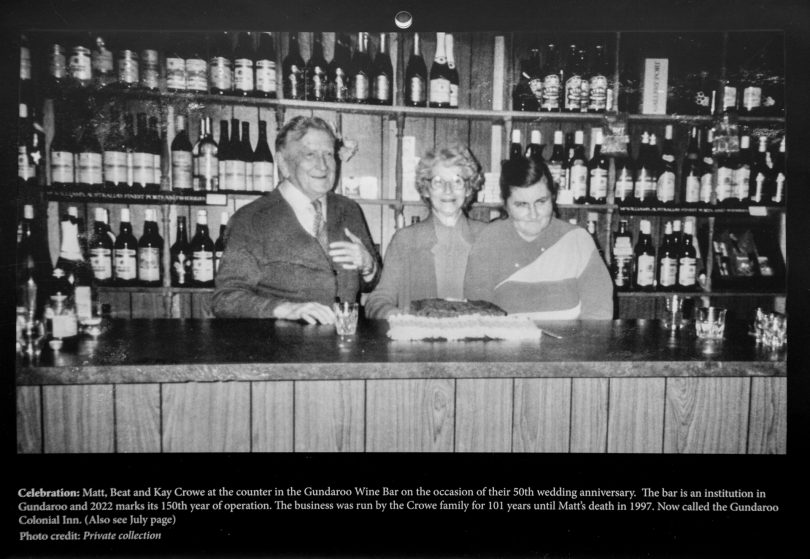

Matt, Beat and Kay Crowe behind the bar at Crowe’s Wine Bar, the heart of the village of Gundaroo for many years. Photo: Gundaroo Historical Society.

Today, it’s edging towards becoming a suburb of Canberra, but years ago Gundaroo was a village that could have been a million miles from anywhere.

The centre of its universe was Crowe’s Wine Bar, which operated cheerily for about 90 years before it got a licence to sell beer.

Up until then, you’d order cider or port from Matt Crowe and best ensure there was a stool nearby for when the scrumpy kicked in.

Beat Crowe was always around. If you looked like you’d had a drop too much, she’d take you out the back – not for a hiding, but for a restorative cup of tea. Their daughter Kay was there too, with her remarkable memory.

Don’t quite remember how I landed in Gundaroo. I think a friend of a friend thought it would be a good idea. It wasn’t.

I was working in the Press Gallery at Parliament House at the time, doing the longest of hours and then the added commute time. But I lived in the best house. Today it is the pizza restaurant, but back then it was still known as the old police station, and even came with its own jail cell.

It was the world’s coldest house; you could have set fire to it inside and still frozen to death. But it had a bathroom with black and white tiles on the floor which made up for a lot.

Publication of the Gundaroo Historical Society’s 2022 calendar brought back some of these memories this week, particularly the picture of Beat, Matt and Kay Crowe behind the bar.

When I moved in across the road from the Crowes, I became friends with Beat and Kay. It started when my Labrador puppy Brian started putting on weight at a rapid rate. I knew he was lonely because I worked such long hours, but I didn’t know he’d taken it upon himself to make new friends – with Kay and Beat.

Apparently while I was at work, he’d howl till they came over to visit/feed him – with mutton, lots of mutton. It also began to make sense why he, Brian, was always happier to see Beat than me. He saw her more often.

So I started inviting Beat and Kay over on Saturdays for morning tea. I loved that Beat always wore a hat. And mostly brought a sponge cake with her.

When they came over, Beat would tell me all the goss. I didn’t know many of the people she talked about, but it did sound like they led interesting lives. Kay would play with Brian and feed him mutton and cake, simultaneously. He’d bring it all up again, but mostly waited till they left.

I’d always take friends to the wine bar to not drink beer and listen to Matt’s stories. He told the same ones, but they grew better with the years till they were practically legends.

If I ever ordered more than a couple of ciders, or someone tried to buy me one, Beat would come out from the back and ask me to go into the kitchen with her on a mission of great importance. It was mostly just to stop me from having another cider – she reckoned two were more than enough for a lady. I loved that she thought I was.

My fondest memory is of the early mornings when the village was mostly still asleep. I’d lie in bed to hear a swishing sound. It was Beat, sweeping the front of the wine bar in her threadbare cotton coat over an even more threadbare nightie.

When she died some years later, I was with some of her friends at the wine bar after the wake, helping to sort her belongings for Kay. One of the women brought out a big parcel, still secure in its David Jones bag. It was the wool dressing gown I’d bought Beat years before so she wouldn’t freeze to death in the early mornings.

“Look at this,” one of the women said. “I remember when someone bought this for her. But she never wore it – she was saving it for best.”