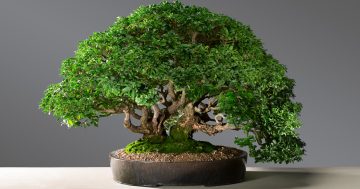

An 83-year old cypress bonsai stands at less than one-metre tall at the National Bonsai and Penjing Collection of Australia at Canberra’s National Arboretum. Photo: Michelle Rowe.

There’s no shortage of galleries in Canberra with something to suit every interest.

There’s grand exhibitions at the National Gallery of Australia, incredible military paraphernalia at the Australian War Memorial, wonderful artistic finds at the privately owned Beaver Galleries, and the book lovers’ utopia, the National Library of Australia. There’s even a display of dinosaurs on the outskirts of town at The National Dinosaur Museum.

But did you know about the small, but perfectly formed, National Bonsai and Penjing Collection of Australia at the National Arboretum?

Like Gulliver unexpectedly washing up on the island of Lilliput, I stumble across this miniature world after stopping for afternoon tea at the Arboretum Cafe.

In a fittingly compact courtyard next to the cafe and gift shop, more than 70 trees – seemingly the victims of the electromagnetic shrinking machine from 1989 flick, Honey, I Shrunk the Kids – are on display.

The miniature tree world is a magnet for photographers at the National Arboretum. Photo: Michelle Rowe.

Towering Australian natives such as eucalyptus, banksia and freshwater paperbark have been reduced to a fraction of their normal size. Alongside them sit Chinese junipers, Japanese maples and English oaks that have been the focus of similarly obsessive pruning, training, styling and maintenance over many years.

As I lean in to check out some tiny figurines placed deep within one of these quirky outdoor scenes, one of the collection’s volunteers, Sisto, strikes up a conversation. He offers advice on how best to capture the detail of each display in an image – crouch down, get close to the tree and aim the lens upwards.

He’s right, I am producing better shots immediately.

Sisto is one of a large number of volunteers – many of them members of the Canberra Bonsai Society – who offer their time to look after the display and provide information to visitors.

He tells me there are two types of art form here. The first is bonsai, which has been practised in Japan for about 1200 years and involves the growing of miniature trees and shrubs in containers through regular pruning of the roots and branches.

Then there’s the ancient Chinese art of penjing, from which bonsai originated, in which miniature landscapes can include rocks, ground covers and small objects or figurines.

The penjing display I’m looking at is a 38-year-old Chinese juniper that has been styled and trained since 1988. It features a tiny trio of characters perched on a mossy embankment, deep in conversation. A nearby display depicts three deer running through the landscape and tiny birds landing on its leaves.

Three tiny characters appear deep in conversation within a penjing display. Photo: Michelle Rowe.

Such is the time, skill and patience involved in both disciplines that the trees are often handed down through generations of families. And while normal size trees can live for thousands of years, bonsai and penjing landscapes can live indefinitely due to the constant trimming and promotion of new growth.

The thing that strikes me most about these miniatures is the detail – the gnarled bark, the perfectly formed leaves and the tapering branches are an exact representation of their originals.

When I photograph the Chinese juniper close up, capturing other displays in the background through its boughs, it appears absolutely life size. The same with a Himalayan cedar that would normally stand up to 40m high but is no more than a metre tall here.

Sisto suggests those fascinated by the display – and nature in general – should consider visiting four times a year, at the beginning of each season, to get the full experience of these ever-changing life forms.

The National Bonsai and Penjing Collection of Australia at the National Arboretum. Photo: Michelle Rowe.

He also dispels the notion that bonsai and penjing are a mystical practice that only a chosen few can get right.

“You can buy a $20 tree at the nursery and fight your way through the tutorials on Google to learn how to do it,” he says, adding that he’s working on a couple of miniature trees at home. “You can bonsai almost anything – even fig trees.”

As we drive out of the Nation Arboretum, surrounded by 250 hectares of living forests and gardens and breathtaking views, I’m reminded that it’s the little things in life that count.

The National Bonsai and Penjing Collection of Australia is open daily between 9 am and 4 pm at the National Arboretum.