Dr Gabrielle Gross, pictured right at her first ANU graduation with mum Noeline Ikin (also pictured at her graduation) is her biggest inspiration. Photo: ACT Government.

For one of Canberra Hospital’s newest recruits – junior medical officer Gabrielle Gross – the path to becoming a doctor wasn’t linear.

It started when her mum Noeline Ikin was diagnosed with brain cancer and Dr Gross became her primary carer.

“After she became sick, she became hemiplegic – paralysed on the left side of her body – and she needed someone with her 24/7,” Dr Gross explained.

While she was always empathetic towards anyone or anything suffering – Dr Gross described herself as the “kid crying if the dog or the horse was hurt” – it was only when she spent so much time in hospital with her mum that she realised how important it was to have empathy as a doctor.

“I decided to go into medicine as I thought it was a space where that skillset was needed,” Dr Gross said.

Ms Ikin, who died in 2017, is remembered as a rural advocate and former political candidate who rose to public prominence after almost toppling Bob Katter in the 2013 election.

For Dr Gross, her mum remains her biggest inspiration.

“Some of the patients that will be on my ward do have cancer, and I have a particular fondness for those patients because it very much reminds me of the reason that I am in medicine,” Dr Gross said.

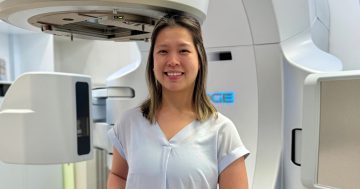

Canberra Health Services acting executive director, medical services, Ashwin Swaminathan and Dr Gabrielle Gross. Photo: ACT Government.

A total of 115 junior doctors joined the teams at Canberra Hospital and Calvary Public Hospital Bruce on Monday (7 February).

Over half of them, Dr Gross included, studied at the ANU Medical School.

It’s been a disrupted final few years of study for the cohort, with the pandemic forcing many classes online, although Dr Gross thinks there were some hidden blessings.

“I think the big message from that was how to be very resilient as students and learning how to adapt to whatever was being thrown at us,” she explained.

“One thing that it did really well was that it enhanced our clinical reasoning skills because we would be presented cases online – and you’d really have to stop and think about it.”

Not only were classes online, but placements would also often have to be paused or adjusted due for some time due to COVID-19 cases.

“It was a really interesting experience in uncharted waters in a lot of ways,” Dr Gross noted.

It’s also still uncharted waters, as Dr Gross and her peers are about to begin their medical careers in the middle of a pandemic.

But Dr Gross said the pandemic hasn’t necessarily changed how she feels about her responsibility as a medical professional, although there is perhaps an increased sense of duty to the community.

“It was really difficult being at home sometimes and studying to be a doctor and seeing things happening and staff shortages, and you really want to get involved and help out,” she said.

“More than anything, I’m just looking forward to finally getting to put into practice what I’ve learned in medical school.”

Dr Gross said she’s also grateful for the community to have helped her get to where she is today.

“Some of the patients in hospital right now are the ones who let me listen to a heart murmur or a chest for the first time – and now they are people I get to look after,” she explained.

The responsibility and privilege that comes with taking on a role that requires the trust of patients also weighs on Dr Gross.

“Throughout med school, I’ve gone home some days and thought about how privileged I am to be involved in patient care and for people to be in vulnerable positions and to trust me enough to tell me things they might not have told somebody else,” she said.

As a Junior Medical Officer, Dr Gross will complete one year of supervised training as an intern before she and her peers are eligible for general medical registration.