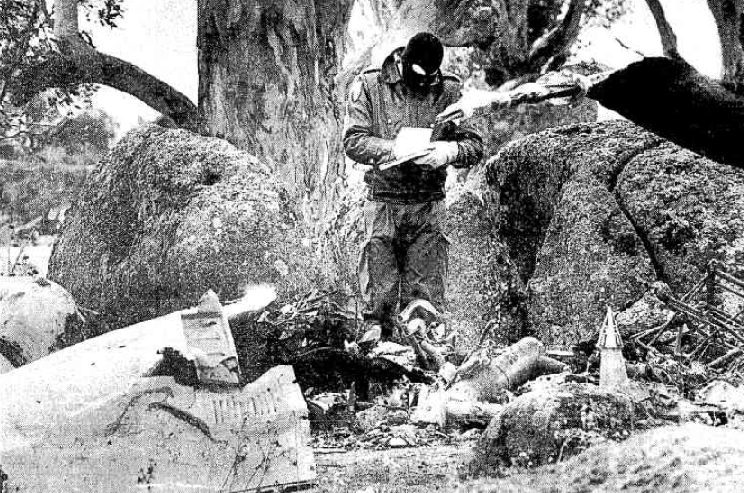

Police officers at the scene of the Monarch Airlines crash near Young 30 years ago. Image: National Library of Australia.

Thirty years ago on this day – June 11 – a small 10-seater Piper PA31-350 Navajo Chieftain attempted several landings from the south of Young’s airport around 7:10 pm.

Travelling from Sydney – the Monarch Airlines flight OB301 flight carried seven occupants, including the two pilots.

It was a bleak moonless night, so characteristic of June in the NSW South West Slopes, one where low cloud and darkness conspired with blowy, icy conditions and undulating tree-scattered terrain to challenge any pilot flying into the small aerodrome.

Two flights were scheduled for arrival. Waiting families and friends huddled in the small stark aerodrome building.

From above, the only sign of life below was the light from that building and tarmac lights. From below, the unmistakable drone of an engine, flashing small wing lights as the craft circled the airport.

One aircraft landed that night. The other didn’t.

Searching beyond the rain-shrouded landing strip on a hill, a light was sighted. It remained stationary.

That light was a fireball; the result of Monarch Airlines flight crashing into a hill on approach, first hitting three successive trees, leaving what remained – the fuselage – to land on a boulder, split in two, one part landing on the plane’s already severed right wing before incinerating in a fire fed from an estimated 366 litres of aviation fuel.

Everybody on board died as a result of the impact and fire. One not immediately.

One survivor had been thrown from the plane. She was discovered near the wreckage around 8 pm. The following morning in Sydney’s Camperdown Children’s Hospital she succumbed to her injuries.

She was one of three Pymble Ladies College students – Allanda Clark, 16, Jane Gay, 14, and Prudence Papworth, 14, – homeward bound from boarding school on a flight that included popular Cootamundra councillor Stephen Ward, 42, and Queens Counsel William (Bill) Caldwell, 45, whose farming family have long been connected with the district.

Also killed were the pilot Wayne Gorham, 42 and co-pilot Brynley David Baker, 24.

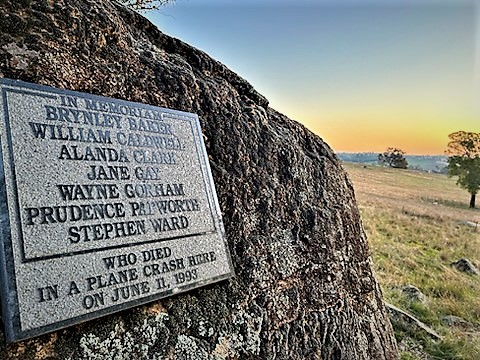

Today a bronze plaque fixed to a granite rock atop that hill memorialises those seven killed. But the anguish is still lugged around in the hearts and memories of those whose recollections of that crash remain undimmed.

One of those people was John Sharpe.

Away with his wife celebrating their anniversary – he took an early morning call from a friend to see if he was still alive.

“I said “yes, why do you ask,” and the caller said the local radio was saying a politician was killed in that crash last night,” John told Region.

John had notched up nine years with the Nationals representing Gilmore which had been redistributed into Hume.

He’d grown up beside and overlooking Young airport – his sister and he with their parents on a historic property called “Clifton”. Also a pilot, he was a member of the Young Aero Club.

“So I knew that the airport runway in the surrounding territory pretty well, and I knew about that hill,” he said.

Bar the co-pilot, he also knew everybody on that flight.

A memorial plaque at the site of the June 11, 1993 Monarch Airlines plane crash near Young. Photo: Duncan McGregor.

Days after the crash, the MP who was also the federal shadow transport minister, stood at the site with an overpowering sense of responsibility in finding answers.

“Yes, it was personal – I knew most people on that flight and their families, I was standing on the burnt grass trying to work out, like everyone else, how this had happened”.

Time froze as news of the crash reverberated around the district – to this day, most recall with unmistakable clarity what they were doing when they heard.

“The feeling in the community at the time was obviously very overpowering because we’d lost six people from the local area. Many of them young kids, high school kids coming home for a long weekend,” he said.

“I made it my mission to pursue the reason why this crash had occurred.”

Thirteen months later, the Bureau of Air Safety Investigation’s (BASI) official report said the final uncommanded descent was merely a culminating factor. Weather and climate were implicated. The weather evident; the climate less visible but equally real: the priorities, assumptions and values under which the airline and its regulator operated.

Missing instruments, inadequate training and commercial priorities; the airline had been red flagged six weeks earlier but remained operational.

The day following the crash, John said, bizarrely, it continued flying into Young.

“What I couldn’t work out was how this could occur right under the very nose of the then Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) when they were literally almost next door to Monarch’s offices and building and all these things were going on right under their nose.”

“As somebody who’s been a pilot, you understand these things moderately – you sort of say to yourself this surely couldn’t have happened if the safety regulator was doing its job.”

Also buried beneath Monarch’s wreckage, rattling revelations about national airline safety regulation, showing systemic failures in the CAA’s safety surveillance operations.

“People were coming to me with all sorts of stories about what was going on and how the rules were being bypassed and airlines were operating unsafely,” John said.

“The more I learned, the more incensed I became, and the more motivated to make changes. I became emboldened,” John said, “because when you make these claims publicly, you get criticized by all sorts of people – they really hop into you and they call you all sorts of things, but you get to get involved because you think ‘you can say all that, but guess what?'”

“People die when you get it wrong. And you’ve got it wrong, and people are dead. And to me, that’s completely unacceptable. And we can’t let it happen again. And I’ll do my best to make sure it doesn’t.”

One CAA whistleblower would bleed official files concealed in rolled-up copies of The Canberra Times to John’s chief of staff, also carrying a rolled-up copy of the paper, at Woden Bus Interchange.

With this, John had the ammunition necessary to campaign against the CAA with parliament as his platform.

On 4 May 1994, he warned parliament of an airline operating so dangerously it was putting people’s lives at risk if it continued to fly.

John said it gave him no satisfaction that those concerns were most sadly proven correct by the Seaview crash in October that year.

By July 1995, the CAA had been split into an airspace management organisation called Airservices Australia, and an aviation safety authority, the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA).

In 1996 John became federal transport and regional development minister, initiating a complete rewrite of the CASA’s regulations with robust powers still enforced today.

“I’d like to think we’ve reduced the risk of flying, reduced the accidents,” he said.

William Caldwell’s wife Hilary became a founding member of the Airline Passenger Safety Association, was a consumer representative on CASA’s Program Advisory Panel (PAP) and, in 2000, was appointed to a new consultative body, the Aviation Safety Forum, formed to provide strategic advice to the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA).

“I wanted her there to oversight operations so at least they have somebody who knows what it’s like when you get it wrong,” John said.

“Monarch was a tragedy that should never have happened, as was Seaview and I look back and I think, because of all that things are safer, we’ve fixed a lot of those problems and the effort was worth it,” John said, “nothing will bring those people back you realise, nothing’s ever going to bring them back”.

Original Article published by Edwina Mason on About Regional.