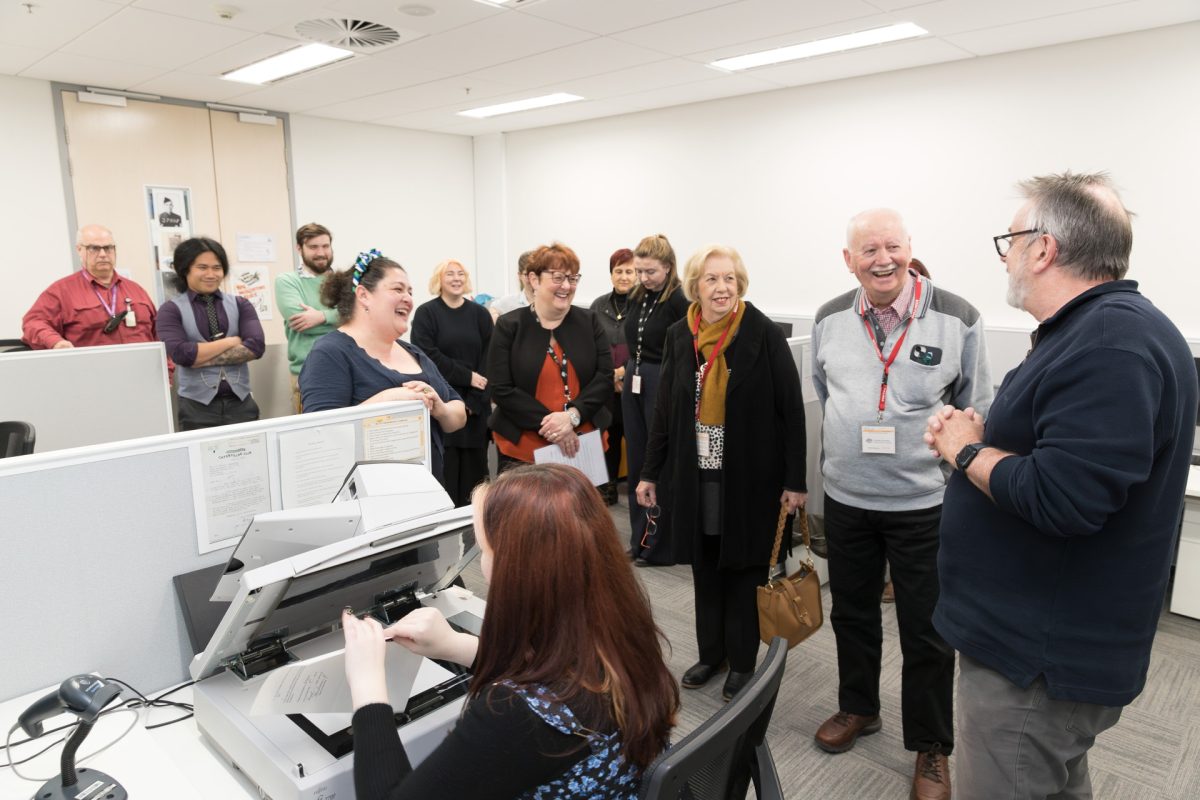

Robert Williamson and sister Carol Miller being shown the restored files by National Archives of Australia director of preservation Travis Taylor. Photo: National Archives of Australia.

“She would be so honoured.”

Carol Miller was close to tears. She and her brother, Robert Williamson, came down from Sydney to witness their mother’s wartime service records being added to the National Archives of Australia digital collection.

It marks the end of a five-year, $10-million project to digitise the more than one million World War II service records kept by the archives.

“We’re just everyday people,” Carol told Region.

“Of all the people who served overseas or at home like our mother – she was just a small person supporting those who helped give freedom to our country, for which a lot gave their lives.

“We know she’d be so humbled.”

National Archives of Australia Assistant Director General Josephine Secis and Project Director Rebecca Penna with Carol Miller and Robert Williamson. Photo: National Archives of Australia.

The National Archives collects Australian Government records to “preserve them, manage them and make them public”.

More than 45 million items are kept in storage facilities across the country, available on request, but there have been efforts in recent years to make digital copies available through the National Archives website.

In 2019, the National Archives was awarded $10 million from the government to digitise its WWII records.

These include enlistment forms (with personal details like age, medical conditions and next-of-kin), service and casualty forms, discharge forms, and negative photographs of the Australian men and women who served in the Army, Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) and Royal Australian Navy from 1939 to 1945.

Last month, the National Archives put out a call for the public to help locate the family of Margaret (or ‘Peggy’) Williamson, the subject of the last record to be digitised.

Margaret (or Peggy) Williamson. Photo: National Archives of Australia.

“Margaret’s service record represents the culmination of years of effort to digitise these paper records, but also an opportunity to honour the memory of the many individuals who served the country,” project director Rebecca Penna said.

Margaret was born Margaret McCredie in Paddington, NSW, in 1920. She went to Bankstown Domestic Science School and worked in the mail order department at David Jones on Market Street before enrolling on the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF) at the age of 20.

During her time in the WAAAF, Margaret worked as a storekeeper and equipment assistant in various locations across Australia, including Robertson, Parkes, Point Cook, Laverton and Sydney.

More than one million WWII files are now available on the National Archives website. Photo: National Archives of Australia.

She was promoted to sergeant in April 1944 and discharged on demobilisation in October 1945.

Her husband, Richard Williamson, was born in Kyabram, Victoria, and also served in WWII.

The NAA managed to track down their children, Carol and Robert, both living in Sydney and invited them for a tour of the Mitchell storage facility to see how the digitisation process works.

Carol said her parents never really spoke about their experiences, “and I regret I didn’t question it more”.

“Towards the end of mum’s life, I started writing on the back of some of her photographs and asking her questions, but she didn’t elaborate.”

Robert added, “They didn’t talk about the war in general – that was something that had happened.”

The Peter Durack Building in Mitchell opened in 2017, houses more than 100 km of paper records and 10 km of audio-visual material, along with purpose-built photography studios and cold-storage rooms.

Travis Taylor has worked there for nearly 20 years and says digitising the records has been a “race against the clock”.

The negative photos slowly dissolve over time as the nitrate in the film interacts with moisture in the atmosphere to form nitric acid.

“The negative starts to get all sticky, and with more time, eventually shatters, and there’ll be no image at all,” he explained.

Each file is scanned by hand. Photo: National Archives of Australia.

The photos are often kept in paper files, where the acid can leak and stain the files, so the first point of order was separating the two.

The files were scanned individually on flat-bed scanners, and the photos were developed in the studio. The original negatives are then placed in cold storage, kept at minus-18 degrees Celsius, to slow the decay.

“So if we ever need to re-digitise them in the future – maybe with 1000-megapixel cameras – we still hope to have them here,” Travis said.

The job has been a “real eye-opener” for his team, coming across everything from X-rays showing shrapnel injuries to written correspondence to the families of those men and women who lost their lives.

“It’s really sad but really rewarding in that we’re making people’s history accessible.”

To search for a service record, visit the National Archives.