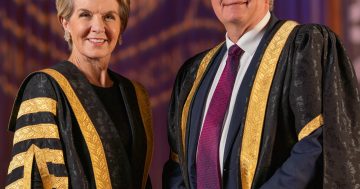

ANU Vice-Chancellor Brian Schmidt: “Democracies don’t function without trust. And democracies cannot evolve without trust.” Photo: National Press Club of Australia.

Australian democracy and the institutions that support it are buckling in the age of misinformation and need bolstering to avoid political paralysis at a time of mounting challenges, Professor Brian Schmidt has told the National Press Club in his last speech as ANU Vice-Chancellor.

Professor Schmidt said that at the core of this threat to democracy was a loss of trust in politicians and government, exacerbated by the 24-hour news cycle and the flood of uncurated and evidence-free views on social media.

He said ANU research had found only a quarter of Australians thought that people in government could be trusted.

“This suggests Australian democracy itself is in peril,” he said.

“Democracies don’t function without trust. And democracies cannot evolve without trust.

“Voters are concerned about what governments are doing. And they don’t think political leaders have their interests at heart. It is possible, then, that they are beginning to believe that the government is not a representation of them.

“This should be a wake-up call for Australia.”

Using the example of the Voice referendum as how this paralysis might set in, Professor Schmidt said that an ANU analysis showed that 87 per cent of those surveyed said Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders should have a say, or a voice, over matters that directly affect them, and 76 per cent of ‘No’ voters also thought they deserve a voice when it comes to key policies and political decisions.

“And yet, 60 per cent of Australians voted against a Voice,” Professor Schmidt said.

He said the referendum may still have succeeded if there had been bipartisan support, but a lack of trust sank it in the end.

“It is easy to say ‘no’ in democracies: ‘If you don’t know, vote no’. But ‘Yes’ is what enables our democracy to evolve and meet new challenges and opportunities.”

Professor Schmidt said the merchants of doubt were deliberately setting out to confuse the public to stifle change.

He said democracy could not function effectively without evidence and knowledge, but these were competing with a torrent of alternative facts in a space where experts were increasingly derided.

“An environment where invention and hard fact can sit indistinguishably side by side, one as credible as the other, is paralysing our democracy,” he said. “It means people in power can survive by avoiding the wicked problems and instead make decisions on 8-second soundbites rather than proven fact.”

Professor Schmidt said the manipulation of information would only get worse with the application of artificial intelligence tools, particularly during election campaigns, contributing to not just paralysis but political dysfunction, which was only too evident in his home country of the United States, where former president Donald Trump continued to cast a shadow.

He said it was vital that universities, as guardians of knowledge and places of debate, retained their autonomy and academic freedom, saying it was corrosive to undermine trust in academic institutions.

“We are not flawless. But we pursue the truth without a political agenda or a paymaster,” he said.

“We follow the evidence and are transparent in our methods and outcomes. There has to be space in a functioning democracy for experts to debate – those places are called universities.”

Professor Schmidt said trust in the digitally disrupted news media was also down and called for reforms that could return it to being a highly trusted institution that informed the public and helped it hold all of society’s institutions to account.

He suggested an accreditation system akin to that used by universities.

“How about if, in order to be an official media organisation, and be given specific rights and protections, you have to accredit against a series of standards?” he said.

“We need the media sector to think deeply about its role in society and be open to reform.

“Nothing less than the health of our democracy rests on restoring public trust in their news providers and in maintaining it in our universities.”

He noted Australia had three democratic pillars going for it that other countries did not – mandatory voting, preferential voting and the independent Australian Electoral Commission.

“These three key pillars that underpin Australia’s democratic resilience were not in place at our country’s inception but have been added over time,” he said.

“These were major changes, where Australia and its politicians had to say yes to change.”